Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Humanity has eliminated only one infectious disease—smallpox.

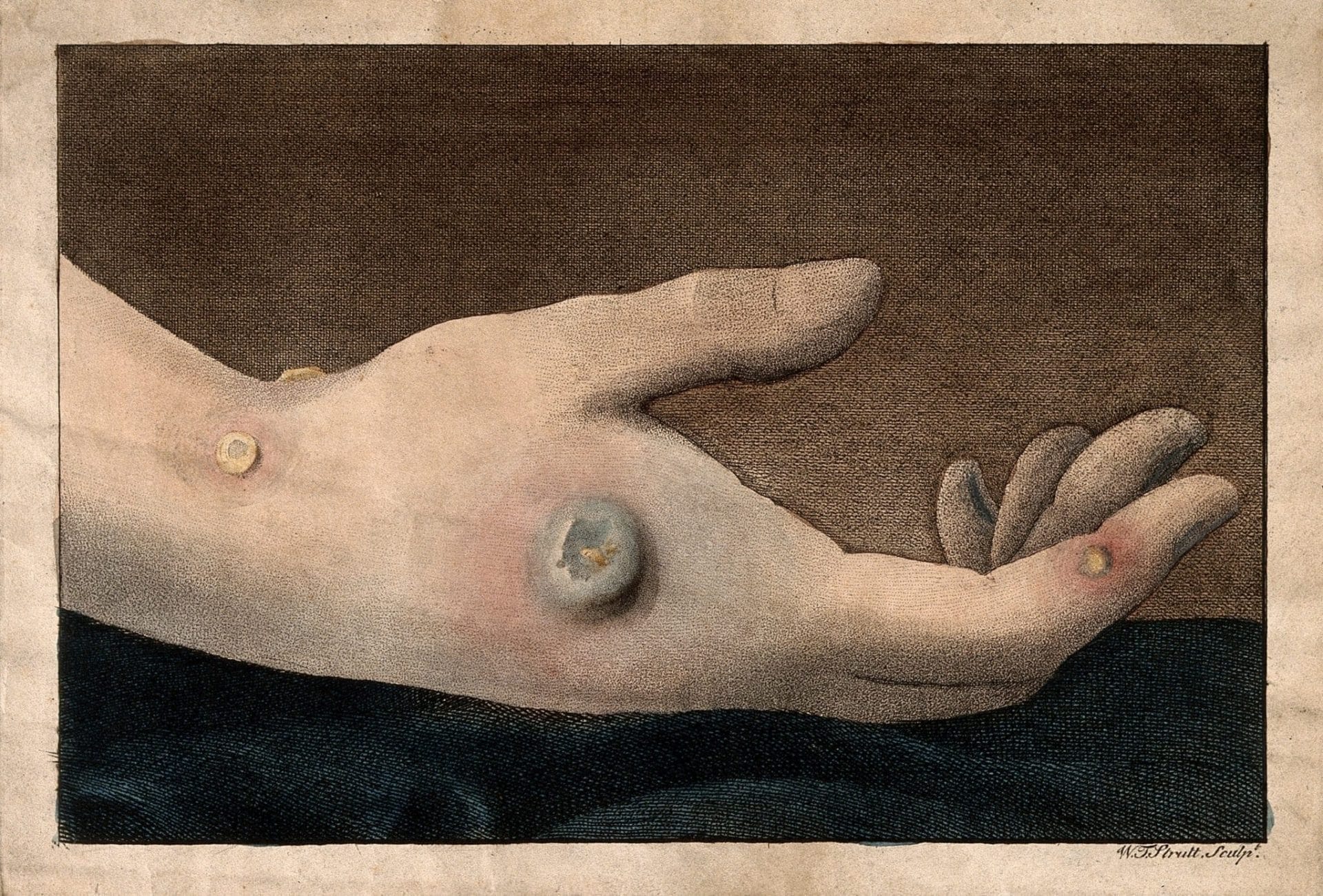

Smallpox is a very old disease and efforts to prevent it are almost as old. They included a technique called variolation, also known as inoculation or engrafting, in which individuals were infected with live smallpox virus to produce a milder form of the disease. They still developed smallpox and were contagious, but the risk of death and serious complications were drastically reduced.1

The first reliable records of the disease come from China in AD 5,2 but skin lesions thought to be the result of smallpox appear on Egyptian mummies from 1570-1085 BC. Assuming these lesions are from smallpox, the disease likely appeared with early farming settlements in northeastern Africa. From there, it presumably traveled north with Egyptian merchant vessels.3

Some of the earliest written records of variolation come from China and India4 and the practice was well known in China by AD 1500,5 where the typical method was inserting dry scabs into the nostril of the recipient. In AD 1661, variolation influenced the Qing dynasty. Smallpox had killed emperor Fu-lin and was particularly prevalent among the Manchu people.6 Emperor Kangxi (K’ang Hsi), son of Fu-lin, had survived smallpox as a toddler. His immunity to the disease made him preferable as a ruler over his brothers, who had never had the pox. He was selected to be emperor when his father died, despite being the youngest. In Kangxi’s later years, he would institute a variolation program among his regular troops, protecting them, in his words “as I did my own children.”7

The overall evidence suggests that variolation began somewhere in Asia, traveled to China and then on to Persia and Turkey,8 where it would catch European attention. The most well-known form of variolation was practiced in Turkey. As recorded by Lady Mary Wortley Montague, who lived there with her ambassador husband: “a set of old women performed the operation by scratching open a vein in the patient and putting into it as much of the smallpox venom as could lie on the head of a needle.”9 The wound was then covered with a nutshell. Lady Mary had enough faith in this practice that she had her son variolated this way.

One story held that women from the Caucasus were considered especially beautiful in Turkey and married into the country because they had been variolated and were unscarred by smallpox.10 It is possible that these women went on to teach others the technique or to variolate others themselves, establishing the practice Lady Mary observed.

When Lady Mary’s family returned to England, a smallpox epidemic was raging. She had her daughter variolated and advocated for its widespread practice in England. Her efforts eventually resulted in the variolation of members of the royal family and an official experiment involving six Newgate prisoners.11,12

Variolation faced intense pushback from clergy in England, who said that the practice was counter to God’s will. However, after the Newgate experiment proved effective and the royal children survived their treatment, variolation became incredibly popular. As the practice spread, it evolved into an elaborate process of weeks-long preparation including special diets, cycles of purging and bleeding, and extensive recovery periods.13,14 From 1721, the year of the Newgate experiment,15 to 1728, physicians would variolate 897 people. Only seventeen of them would die, compared to the 18,000 total deaths from smallpox in those same seven years.16

Interestingly, variolation existed as a folk practice in Europe before Lady Mary’s introduction. Thomas Bartholin mentions it in a note published in 1675 and it could be found in rural France and Wales at that time.17 Parents would “buy the pox” by purchasing scabs or dried pustules from the parent of a child recovering from smallpox and tie them on to the arm of their own child, or deliberately put one child to bed with another who had mild smallpox.18

“Modern” variolation—reintroduced from Turkey—was first brought to the Royal Society by physicians Emanuel Timoni (or Timonius) and Jacob Pylarini (or Pylarinius), but the Society considered their reports a novelty, not worthy of investigation. However, after variolation’s rise to popularity in England many English physicians became popular elsewhere in Europe for offering variolation services.19

In Austria, Empress Marie Theresa promoted variolation after recovering from the pox, and this may have encouraged her daughter Marie Antoinette to do the same for the royal family in France.20 Another empress, Catherine the Great, would advocate for variolation in her country of Russia.21,22 Praise was not universal, however, and Voltaire recorded the opinion of some Europeans about the technique:

“The English, on the other side, call the rest of the Europeans cowardly and unnatural. Cowardly, because they are afraid of putting their children to a little pain; unnatural, because they expose them to die one time or other of the small-pox.”23

This was not entirely surprising, as many discredited the practice for its non-European origins and its introduction by a woman.

Variolation in the United States was introduced by enslaved Africans and supported by texts from England. At the intersection of these two points was the Reverend Cotton Mather. Mather learned of variolation from Onesimus, an enslaved African man given to him by his parish. When Onesimus was asked if he had had smallpox before, a typical question posed to enslaved people, he said “both, yes and no.” He then explained that he had “undergone an operation which had given him something of the small-pox” while at the same time protecting him from it. He said that this was common in the land he had been taken from. Mather consulted other enslaved Africans in Boston who confirmed the story, and many showed scars from the procedure to prove it.24

Little information survives on the original homes of the enslaved Africans brought into Boston. European travelers in Africa noted the practice throughout the southern and eastern regions of Africa before 1900, but the practice was likely more widespread than records suggest. The technique used was in line with the Turkish style of variolation, utilizing cuts on specific parts of the body that were then infected with wet matter, but some areas in the northeast also “bought the pox.” 25

Mather was a theologian and scholar interested in science and medicine. He was a member of the Royal Society of London (the eighth colonial American elected) and kept regular correspondence with its members.26 When Timoni and Pylarini’s writings on variolation appeared in the Transactions of the Royal Society for 1714, he replied, writing to English physician Dr. John Woodward that the reports matched accounts of the enslaved Africans he had spoken to.27

Thus, when smallpox broke out in Boston in the summer of 1721, Mather saw no reason to keep a life-saving practice from the people. He did not variolate himself, but he wrote to doctors in the Boston area and convinced Dr. Zabdiel Boylston to begin the practice.28,29 Boylston first variolated his six-year-old son and two enslaved Africans. All three survived and he then went on to variolate 200 other Bostonians.

Boylston had received most of his training through apprenticeships but had not been formally educated, as was the case for most Boston physicians at that time. This irked a leader of the opposition, Dr. William Douglass, who had been educated at the University of Edinburgh30 and wanted medicine to remain in the hands of university-educated physicians.31 Douglass privately supported variolation and may have done so publicly if it had been advocated for and performed by these kinds of physicians.32

Boston clergy joined Mather in supporting variolation while physicians fought against it. Physician opposition made sense, as the practice ran counter to the major medical theories at the time. Diseases were treated by the expulsion of harmful matter, so inserting diseased matter into a person seemed completely illogical.33

Mather and his supporters pushed hard for variolation in the United States and England, drawing verbal and material threats. The conflict rose to the point that a bomb was thrown into Mather’s house.34 Numbers, however, could not be debated, defamed in pamphlets, or scared into silence. By the end of the severe 1721 epidemic in Boston, over 5,000 people had contracted smallpox, and 844 had died.35 Of the 287 variolated during the 1721 epidemic, only six had died.36 When a second, less severe epidemic began in 1730, variolation was taken up readily.

In one final role in United States history, variolation influenced the American Revolutionary War. In 1766, soldiers fighting alongside George Washington were plagued by smallpox and unable to take Quebec from British soldiers, who had been exposed to or variolated against the disease. Eleven years later Washington required soldiers to be variolated before service.37,38

Then, in 1796, Edward Jenner introduced vaccination, inducing immunity by using material from patients with cowpox, a virus immunologically identical to smallpox. Jenner reportedly had vivid memories of suffering smallpox while he recovered from his own variolation as a child, and he hoped vaccination would prevent this same suffering in others.39 Jenner’s pioneering vaccine was a death sentence for variolation—and smallpox.

The Vaccination Act of 1840 banned variolation in England,40 but it persisted elsewhere even as vaccination took hold. This sometimes led to conflict and new epidemics of the disease, as was the case for a Palestinian village in the 1920s.41 But in the end, vaccination replaced variolation worldwide. Variolation’s global journey was complete, its foe vanquished, and humanity safer for it.

Notes

- William L. Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” Scientific American vol. 234 no. 1 (January, 1976): 112, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/24950265.

- Robin A. Weiss, José Esparza, “The prevention and eradication of smallpox: a commentary on Sloane (1755) ‘An account of inoculation’,” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences vol. 370, no. 1666, Theme issue: Celebrating 350 years of “Philosophical Transactions”: life sciences papers (April, 2015): 5, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24498773.

- Stefan Riedel, “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination,” Baylor University Medical Center vol. 18 no. 1 (January, 2005): 21, https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028.

- Arthur Boylston, “The origins of inoculation,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine vol. 105 no. 7 (2012): 311, https://dx.doi.org/10.1258%2Fjrsm.2012.12k044.

- Frank Fenner, Donald A. Henderson, Isao Arita, Zdenek Jezek, Ivan Danilovich Ladnyi, “Early Efforts at Control Variolation, Vaccination, and Isolation and Quarantine” in Smallpox and its eradication, (Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1988), 252, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39485.

- Stuart Fleming, “SCIENCE SCOPE: Smallpox in History: A Killer at Court,” Archaeology vol. 39 no. 9 (November/December 1986): 75, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41731840.

- Ibid.

- Abbas M. Behbehani, “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease,” Microbiological reviews vol. 47 no. 4 (1983): 458, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC281588.

- Robert Halsband, “New Light on Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Contribution to Inoculation,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences vol. 8 no. 4. (October 1953): 393, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24619778.

- Riedel, “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination,” 22.

- Isabel Grundy, Henry Marshall Tory, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1999), 209-220.

- Halsband, “New Light on Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Contribution.”

- Behbehani, “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease 464.

- Fenner, et. al, Smallpox and its eradication, 255.

- Grundy, Tory, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, 213.

- Halsband, “New Light on Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Contribution,” 404.

- Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” 112.

- Fenner, et. Al., Smallpox and its eradication 255.

- Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” 115.

- Weiss, Esparza, “The prevention and eradication of smallpox: a commentary,” 4.

- Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” 116.

- Sarah Jane I Irawa,” Matushka’s ordeal,” Hektoen International Journal, vol. 8 no.2 Infectious Disease (Spring 2016), https://hekint.org/2017/02/01/matushkas-ordeal/.

- Weiss, Esparza, “The prevention and eradication of smallpox: a commentary,” 4.

- Eugenia W. Herbert, “Smallpox Inoculation in Africa,” Journal of African History vol. 16 no. 4 (1975): 539-540, http://www.jstor.org/stable/180496.

- Ibid. 556 (illustration).

- Amalie M. Kass, “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic,” Massachusetts Historical Review vol. 14 (2012): 9, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5224/masshistrevi.14.1.0001.

- Herbert, “Smallpox Inoculation in Africa,” 540.

- Kass, “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic,” 12-13.

- Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” 114.

- Behbehani, “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease,” 464.

- Kass, “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic,” 24.

- Maxine Van De Wetering, “A Reconsideration of the Inoculation Controversy,” The New England Quarterly vol. 58 no. 1 (March, 1985): 52-53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/365262.

- Sara Stidstone Gronim, “Imagining Inoculation: Smallpox, the Body, and Social Relations of Healing in the Eighteenth Century,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine vol. 80 no. 2 (Summer 2006): 255-256, https://www.jstor.org/stable/44448394.

- Riedel, “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination,” 23.

- Langer, “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner,” 114.

- Kass, “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic,” 31.

- Kathryn Tone, ” Washington’s deadliest enemy,” Hektoen International Journal, Infectious Disease vol. 10 no. 3 (Winter 2018), https://hekint.org/2018/03/21/washingtons-deadliest-enemy/.

- Riedel, “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination,” 23.

- Alicia Grant, Globalisation Of Variolation: The Overlooked Origins Of Immunity For Smallpox In The 18th Century, (London: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2019), 8.

- Weiss, Esparza, “The prevention and eradication of smallpox: a commentary,” 9.

- Nadav Davidovitch, Zalman Greenberg, “Public Health, Culture, and Colonial Medicine: Smallpox and Variolation in Palestine during the British Mandate,” Public Health Reports vol. 122 no. 3 (May-June, 2007): https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003335490712200314.

References

- Bayoumi, Ahmed. “The History and Traditional Treatment of Smallpox in the Sudan.” Journal of Eastern African Research & Development vol. 6 no. 1 (1976): 1-10. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43661421.

- Behbehani, Abbas M. “The Smallpox Story: Life and Death of an Old Disease.” Microbiological reviews vol. 47 no. 4 (Publication Month, Year): 455-509. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC281588/.

- Boylston, Arthur. “The origins of inoculation.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine vol. 105 no. 7 (2012): 309-313. https://dx.doi.org/10.1258%2Fjrsm.2012.12k044.

- Davidovitch, Nadav, Zalman Greenberg. “Public Health, Culture, and Colonial Medicine: Smallpox and Variolation in Palestine during the British Mandate.” Public Health Reports vol. 122 no. 3 (May-June, 2007): 398-406. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003335490712200314.

- Fenner, Frank, Donald A. Henderson, Isao Arita, Zdenek Jezek, Ivan Danilovich Ladnyi. “Early Efforts at Control Variolation, Vaccination, and Isolation and Quarantine” in Smallpox and its eradication. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1988. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39485.

- Few, Martha. “Medical Humanitarianism and Smallpox Inoculation in Eighteenth-Century Guatemala.” Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung Vol. 37, No. 3

- (141), Controversies around the Digital Humanities (2012): 303-317. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41636610.

- Fleming, Stuart. “SCIENCE SCOPE: Smallpox in History: A Killer at Court.” Archaeology vol. 36 no. 9 (November/December 1986): 64-65. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41731840

- Grant, Alicia. Globalisation Of Variolation: The Overlooked Origins Of Immunity For Smallpox In The 18th Century. London: World Scientific Publishing Company, 2019.

- Gronim, Sara Stidstone. “Imagining Inoculation: Smallpox, the Body, and Social Relations of Healing in the Eighteenth.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine vol. 80 no. 2 (Summer 2006): 247-268. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44448394.

- Grundy, Isobel, Henry Marshall Tory. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Halsband, Robert. “New Light on Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s Contribution to Inoculation.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences vol. 8 no. 4 (October 1953): 390-405. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24619778.

- Herbert, Eugenia W. “Smallpox Inoculation in Africa.” Journal of African History vol. 16 no. (1975): 539-559. http://www.jstor.org/stable/180496.

- Irawa, Sarah Jane I. ” Matushka’s ordeal.” Hektoen International Journal. vol. 8 no.2 Infectious Disease (Spring 2016). https://hekint.org/2017/02/01/matushkas-ordeal/.

- Kass, Amalie M. “Boston’s Historic Smallpox Epidemic.” Massachusetts Historical Review vol. 14 (2012): 1-51. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5224/masshistrevi.14.1.000.

- Krebsbach, Suzanne. “The Great Charlestown Smallpox Epidemic of 1760.” The South Carolina Historical Magazine vol. 97 no. 1 (January, 1996): 30-37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27570134.

- Langer, William L. “Immunization against Smallpox before Jenner.” Scientific American vol. 234 no. 1 (January, 1976): 112-117. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/24950265.

- Riedel, Stefan. “Edward Jenner and the History of Smallpox and Vaccination.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings vol. 18 no. 1 (January, 2005): 21-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028.

- Skold, Peter. “From Inoculation to Vaccination: Smallpox in Sweden in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Population Studies vol. 50 no. 2 (July, 1996): 247-262. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2174914.

- Tone, Kathryn. ” Washington’s deadliest enemy.” Hektoen International Journal. Infectious Disease vol. 10 no. 3 (Winter 2018). https://hekint.org/2018/03/21/washingtons-deadliest-enemy/.

- Van De Wetering, Maxine. “A Reconsideration of the Inoculation Controversy.” The New England Quarterly vol. 58 no. 1 (March, 1985): 46-67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/365262.

- Weiss, Robin A, José Esparza. “The prevention and eradication of smallpox: a commentary on Sloane (1755) ‘An account of inoculation’.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences vol. 370, no. 1666, Theme issue: Celebrating 350 years of “Philosophical Transactions”: life sciences papers (April, 2015): 1-11. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24498773.

MARIEL TISHMA is the Executive Editorial Assistant at Hektoen International. She has been published in Hektoen International, Bloodbond, Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.