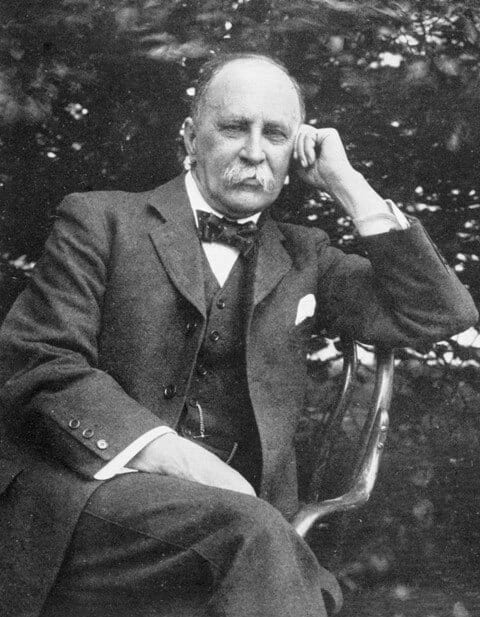

It is good to review periodically the lives of famous men lest they be forgotten by new generations. In medicine few people have been the subject of more books, articles, and reviews then Sir William Osler. He has been called the father of modern medicine. He was the “compleat” physician, a scientist and humanist, and he exerted an immense influence on the medical world of his time. He has also been called “a physician of two continents,” his name being honored as much in England as in America.

Biographical note

Osler was born in 1849 in a Canadian frontier hamlet about forty miles north of Toronto. He learned to use the microscope in high school and did research in biology. He briefly studied theology but then switched to medicine and in 1868 entered the Toronto Medical School. In 1870 he became a medical student at Montreal’s McGill University, which offered better clinical opportunities than Toronto. On graduating in 1872, he spent fifteen months in research in London and described the morphology and function of platelets in blood. After visiting Vienna and Berlin, he returned to McGill and worked for ten years as professor and pathologist at the Montreal General Hospital. He performed hundreds of autopsies, collected interesting specimens, and he wrote careful and complete post-mortem reports.

In 1884 he stopped being a scientist and became clinical professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Elected Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, he delivered the Goulstonian Lecture on malignant endocarditis, studied malaria and the cerebral palsies of children, wrote many articles, and increased his reputation as physician and teacher.

In 1888, Dr. William Welch recruited him to become head of medicine at the newly founded Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore along with William Halsted, and Howard Kelly (shown in the painting The Four Doctors by John Singer Sargent) to develop the premier academic hospital in the United States. The hospital grew considerably in size and reputation between the time when Osler arrived and when he left sixteen years later.

By age fifty-six he was feeling the strain of his over-busy life at Baltimore and in 1905 accepted the position of Regius Professor of Medicine at Oxford University, at the time possibly the most prestigious medical appointment in the world. Promptly plunging into all sorts of social and professional activities, he promoted and extended the work of the Oxford Medical School, was active as physician to the Radcliffe Infirmary, giving ward demonstrations to students and practitioners. He was often called in medical consultations and helped start the Quarterly Journal of Medicine. In 1911 he was elevated to baronetcy by the Coronation Honors List of 1911, becoming Sir William Osler.

He became ill during the Spanish influenza epidemic in 1919 and remained ill for two months before dying of pneumonia at his home in Oxford on December 29. He had stated he wished that his legacy should above all else be as an educator of medical students. He said ”I desire no other epitaph . . . other than I taught medical students in the wards.” As a man of science, he reportedly regretted not been able to conduct his own post-mortem examination, “having taken such a lifelong interest in the case.”

Impact on medicine

Osler’s impact on medicine has been enormous. As pathologist and clinician he became intimately familiar with most diseases affecting mankind, and during his life published around 1,200 articles. He described new clinical entities, refined descriptions of older ones, and brought his extensive experience to fruition in 1892 by publishing The Principles and Practice of Medicine. This was remarkable for being written by one single author, and was translated into French, German, Spanish, and Chinese. He adorned his text with personal references to his vast clinical experience, and with attractive allusions to personalities, ancient and modern. It was unique for its clear, concise presentation, and became the standard textbook of medicine for many years. It finally went out of print in 1947, sixteen editions later.

Osler was aware of the limitations in making diagnoses and prescribing treatments, as expressed in his quote: “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability.” Skeptical of many treatments, he stated that “One of the first duties of the physician is to educate the masses not to take medicine,” and “Remember how much you do not know. Do not pour strange medicine into your patients.” He said that physicians should treat not the disease but the patient with the disease, and emphasized trust and faith in the physician as being more potent than drugs.

His impact on medical education was even more profound. He insisted that students be exposed to patients early in their training. He was proudest of his idea of clinical clerkships, and by their third year the students at Hopkins examined patients, took histories, and carried out laboratory tests instead of merely sitting in lecture halls. As he was fond of saying, “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom . . . live in the ward.” He pioneered bedside teaching, making rounds with a handful of students, demonstrating what one student referred to as his “incomparably thorough physical examination.”

What also set Osler aside from most of his contemporaries was his classical education and familiarity with the great books of the Western civilization. Convinced of the importance of studying the humanities, he believed that a wide view beyond the confines of professional technicalities made a better doctor. In his famous book Aequanimitas, Osler suggested that students could get a liberal education at a very slight cost by reading one of the great books for half an hour before going to sleep and having it open in the morning on one’s dressing table. He himself had more than 8,000 texts and reportedly gave his students the keys to his home in Baltimore, so that they would have unrestricted access to his vast collection. In his will he left his collection to McGill University; it currently makes up the nucleus of the Osler Library at McGill.

Osler in Hektoen International

In our journal we published several articles about this great man, and we offer here excerpts from these articles as well as additional information that might be of interest:

1. Wettrell G: William Osler: clinician and teacher with a pediatric interest. Fall 2020. Physicians of Note.

About one-tenth of The Principles and Practice of Medicine was devoted to disorders and illnesses that primarily affected infants and children. The book was remarkable in his emphasis on the paucity of effective treatments for many diseases.

From the memories of Sir William Osler published by Maude E. Abbott (1926) and Harvey Cushing (1928), it is evident that patients, colleagues, students, and friends were fascinated by his personality, knowledge, wisdom, encouragement, generosity, and personal charm.

2. Wettrell G: Maude Abbott and the early rise of pediatric cardiology. Winter 2016. Cardiology.

In December 1898 Dr. Maude Elizabeth Abbott, assistant curator at the medical museum of McGill University, was sent to study museums and other institutions in Washington, D.C. In Baltimore she met Dr. William Osler, who showed her the pathology department, gave her important reprints, and invited her to dinner. With twelve other young doctors she also participated in a subsequent “students’ night,” discussing medical classics, points of interest, and clinical problems. Osler told Abbott that there was a great opportunity at the McGill museum, and this planted the seed for most of her future work.

3. Raffensperger J: Harvey Cushing: surgeon, author, soldier, historian. Summer 2020. Surgery.

Osler had been a mentor for the younger Cushing and they were friends all their lives. In 1925 Harvey Cushing honored his former friend by accepting the invitation of his widow to write a biography of Osler that won a Pulitzer Prize.

4. Vignette: Bed-side library for medical students. Winter 2012. Education.

Osler suggested that a liberal education may be had at a very slight cost of time and money and advised students and professionals to read for half an hour before going to sleep, and in the morning have a book open on one’s dressing table. It would be surprising, he wrote, how much could be accomplished in the course of one year. His list of books with whom one might make close friends included Shakespeare, Montaigne, Plutarch, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Thomas Browne, Cervantes, Don Quixote, Emerson, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and the Old and New Testament.

5. Fontaine KR: On Longcope Rounds. Summer 2016. Education.

Osler revolutionized medical education by requiring students to be exposed to patients early in their training. As he was fond of saying, “Medicine is learned by the bedside and not in the classroom . . . Live in the ward.” Each morning Osler, impeccably groomed and with a fresh flower in the buttonhole of his Prince Albert coat, conducted what came to be called “rounds.” Trailed by nurses and students, Osler would sit at the bedside, greet the patient, listen to a clinical summary, examine the patient, and facilitate a discussion, keen to ensure that each patient teaches something that could not be found in a textbook.

6. Bonello J.P. and Tsourdinis G.E: Howard Kelly’s avant-garde autopsy method. Winter 2020. Surgery.

Kelly had attracted Osler’s attention during his internship. He often watched him operate and remarked that he had never seen a more skilled surgeon. He offered him a position at the University of Pennsylvania as assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, and in 1884 recruited him to Johns Hopkins as Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology. During his years of service in Baltimore, Kelly devised several gynecologic operations and instruments. He is credited with establishing gynecology as a true specialty.

7. Coulehan J: Walt Whitman: a difficult patient. Winter 2017. Literary Essays.

Osler served as personal physician to Walt Whitman between 1884 and the poet’s death in 1892. Whitman was irritated by Osler’s personality, regarding his cheerfulness as insincere, even though he respected his clinical abilities. It was an uneasy relationship between two intellectual giants, but Whitman stuck with Osler even though he had available other alternatives such as Weir Mitchell.

8. Fiddes P. and Komesaroff P.A: An emperor unclothed. Winter 2018. History.

These authors were “disturbed” by Osler’s lack of interest in modern authors and medical ethics, and perceived his approach shaped by his British “acculturation” and classical education. They felt he was perpetuating a culture dismissive of patients’ rights by his “minor moral lapses” in condoning body snatching, obtaining autopsies at all cost (even paying to secure the desired organs), carrying out autopsies in secret, and removing the affected organs before the formal burial.

9. Radhakrishnan J: Presentism. Fall 2020. Physicians of Note.

In the context of modern presentism, the “uncritical adherence to present-day attitudes, especially the tendency to interpret past events in terms of modern values and concepts,” it appears that Osler has lost his favored status even at his alma mater, where students have decided to drop Osler eponyms because of his disparaging remarks about persons from different countries or races, syphilitics, and alcoholics, as well as being the vice president of the First International Eugenics conference.

10. Sam R: History of endocarditis. Spring 2013. Cardiology.

in 1885 Osler gave a lecture at the Royal College of Physicians summarizing his experience with 200 patients with subacute bacterial endocarditis, describing its clinical features and natural history. He mentioned the occurrence of fever, heart murmurs, and the red painful areas on the finger that came to be known as Osler’s nodes.

11. Kronik G: My father’s glasses. Spring 2011. End of Life.

It was Osler who coined the term “the old man’s friend” for pneumonia developing in the aged and infirm and delivering them from a protracted life of misery, pains, and suffering.

12. Pearce JMS: Walter Russell Brain DM FRCP FRS (1895–1966). Fall 2020. Neurology.

Sir Russell Brain, later doyen of British neurology, attended as a young man the New College in Oxford. In 1919 he met Osler, who at the time was the Regius Professor of Medicine.

13. Co S: The Hopkins Hub. Summer 2016. Hospitals of Note.

In 1873 the banker and philanthropist Johns Hopkins left $7 million to form the Johns Hopkins University and the Johns Hopkins Hospital to provide medical care for Baltimore’s poor and become an integral part of the education of medical students. Crucial to the development of the medical school was the faculty, known collectively as the “Big Four, William Welch, William Halsted, William Osler, Howard Kelly.” Osler helped organize postgraduate medical training into a “residency” system where newly graduated physicians would live or “reside” in hospital-based housing and receive specialized training in treating patients.

14. Dunea G: Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Summer 2015. Physicians of Note.

Osler was preceded intellectually by Oliver Wendell Holmes, also an educated man, who had studied the classics, loved books, and indeed believed that “One must have his books, never part with them, and use them as if his mind were furnished with drawers.” He comments that both Holmes and Osler would have been delighted to hear about computer driven search engines.

Additional quotes from Sir William Osler:

- “The greater the ignorance the greater the dogmatism.”

- “The future is today.”

- “The best preparation for tomorrow is to do today’s work superbly well.”

- “Look wise, say nothing, and grunt. Speech was given to conceal thought.”

- “The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.”

- “He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.”

- “The desire to take medicine is perhaps the greatest feature which distinguishes man from animals.”

- “The young physician starts life with twenty drugs for each disease, and the old physician ends life with one drug for twenty diseases.”

- “The teacher’s life should have three periods, study until twenty-five, investigation until forty, profession until sixty, at which age I would have him retired on a double allowance.”

- “Soap and water and common sense are the best disinfectants.”

- “The natural man has only two primal passions, to get and to beget.”

- “It is much simpler to buy books than to read them and easier to read them than to absorb their contents.”

Leave a Reply