John Raffensperger

Fort Meyers, Florida, United States

|

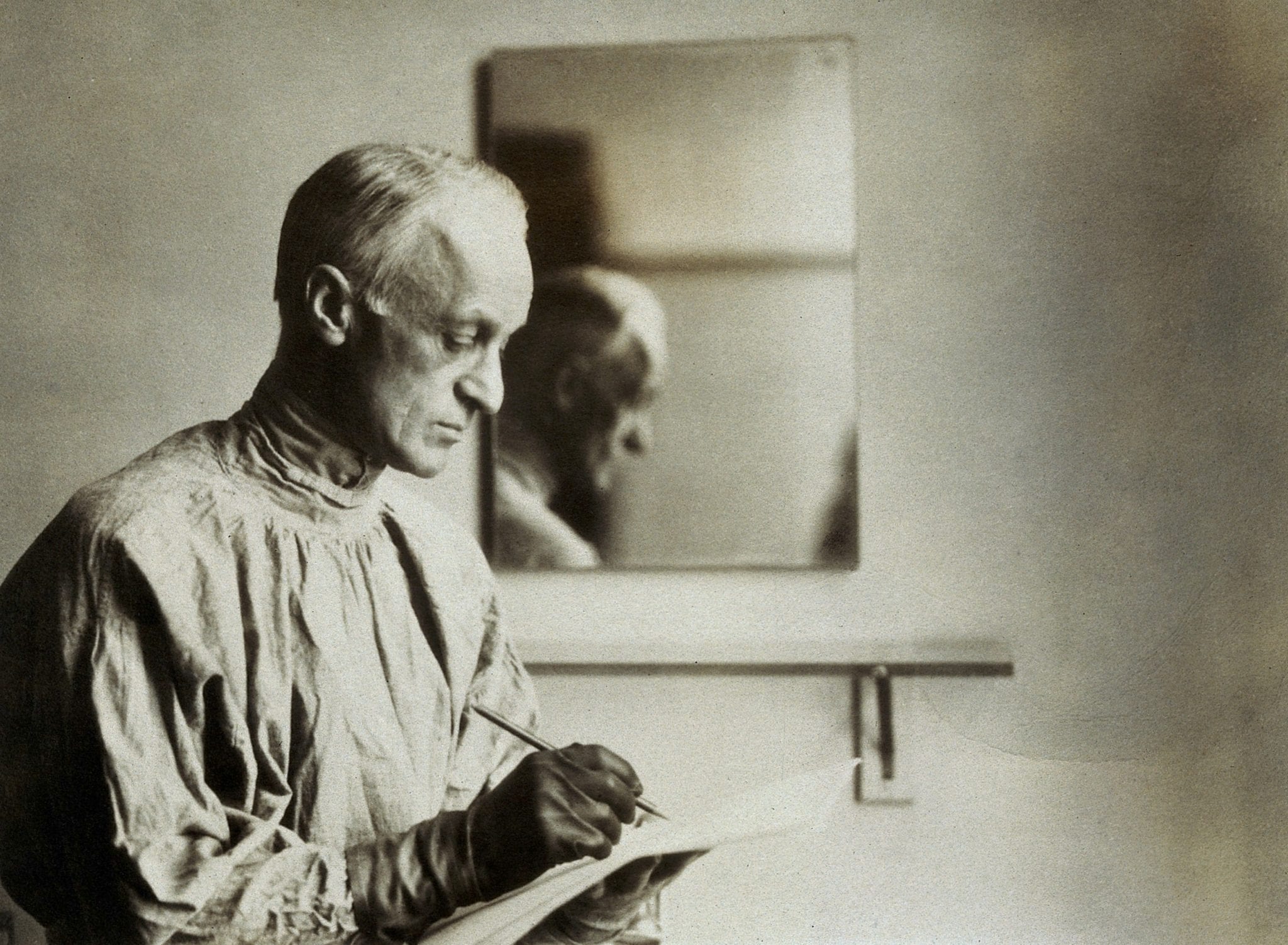

| Harvey Williams Cushing. Photograph by W.(?)W.B. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

Harvey Cushing was a third-generation physician, born to a family of New England Puritans who had migrated to Cleveland, Ohio, in the mid 1830s. His father and grandfather were successful physicians; family members on both sides were well-educated and financially secure.

At Yale, Cushing studied Latin, Greek, literature, and history, but in his third year he turned to medicine. He was captain of the baseball team, rowed, and did gymnastics. He played a part in a school play where he entered the stage with a double back handspring. He was elected to the Scroll and Key Honor Society and graduated from Yale with an AB degree.

Cushing attended Harvard, one of the few medical schools in the country to require pathology, bacteriology, and hands-on laboratory work in addition to the study of patients. Reginald Fitz, who established appendicitis as the cause for right lower quadrant pain, was a Harvard professor while Cushing was a student. His education at Yale put him ahead of his classmates and he skipped lectures to do hospital work. Even in medical school, Cushing’s notes were detailed and illustrated with sketches, often in color. While he was a second-year medical student, he gave an ether anesthetic to a patient with a strangulated hernia. Cushing blamed himself when the patient died on the operating table. During his fourth year in medical school, Cushing worked in the Children’s Hospital and delivered babies in poor people’s homes. During his fourth year he also devised a chart with a fellow student to record the patient’s temperature, pulse, and respirations during anesthesia. At the time, there was no way to record blood pressure, but several years later, while in Pavia, Italy, he saw the Riva-Rocci pneumatic blood pressure apparatus and brought the instrument home. The anesthesia chart would be the only way to record a patient’s vital signs while under anesthesia for the next sixty years.1

Cushing was constantly on call during his surgery internship at the Massachusetts General Hospital. After one long stint of work he said, “Had a great twenty-four hours.” Even as an intern, Cushing did not hesitate to criticize his superiors. Once, after an attending surgeon recommended an amputation, Cushing saved the leg by draining a tubercular abscess.

Following his internship, in 1896 Cushing became an assistant surgeon to William Halsted, the surgeon-in-chief at the new Johns Hopkins Hospital. At first Cushing was disappointed with Halsted, who was slow, fussy, and meticulous and frequently absent from the hospital. But he soon came to appreciate Halsted’s technique and excellent results. He was not as busy as he had been during his internship, and while a junior resident he did research and established the connection between typhoid fever and gallstones.

When Halsted promoted him to senior resident, Cushing re-organized the surgical service by introducing X-rays, anesthesia records, and early operations for patients with intestinal perforation. He was in charge of the surgical service during Halsted’s absences and operated on some of the “chief’s” private patients. Despite being constantly on duty, he found time to study German, play tennis, and do literary work. While still a resident, he operated on Halsted’s wife after an accident and did some of the first intestinal resections and the first splenectomy at Hopkins.

During his residency, Cushing had an attack of abdominal pain shortly after a “wretched dinner.” By his own account, the pain became constant and was localized below and medial to McBurney’s point.

He took a small dose of morphine and calomel, but the pain persisted. The next morning, both Osler, who was the chief of medicine, and Halsted examined Cushing. His white blood count was 13,000. A few hours later, his count has risen to 23,000. At the time, Dr. Cushing, as a result of the influence of Reginald Fitz at Harvard, was well aware of appendicitis and the role of the white blood count in making the diagnosis. Dr. Osler urged delay, apparently because the symptoms were atypical.

Dr. Halsted correctly diagnosed an inflamed appendix, deep in the pelvis. A fellow resident administered a chloroform anesthetic and Dr. Halsted, along with several other Hopkins surgeons, performed an appendectomy. The incision was not a small muscle splitting incision in the right lower quadrant, but a long rectus splitting incision. There was bleeding from the inferior epigastric artery that led to a postoperative hematoma. Halsted closed the incision with silver wire sutures. Later, silk ligatures discharged from the wound.2

During his residency, Cushing practiced on thirty cadavers and then successfully performed a gasserian ganglionectomy on a patient with trigeminal neuralgia. The operation relieved the patient’s unbearable facial pain and launched his career in neurosurgery.

In the summer of 1900, Cushing embarked on a fourteen-month surgical tour of Europe. He was critical of Victor Horsley, the “father” of English neurosurgery, because of Horsley’s rapid surgery with poor hemostasis. In Berne, Switzerland he carried out research on circulation of blood in the brain, and in dogs and monkeys created intracranial pressure to study the effect of pressure and the pulse rate. This work confirmed his interest in brain surgery. Cushing was appalled at the German surgeons’ disregard for patients, saying, “The patient is something to work on, interesting experimental material, but nothing more.”3

On his return to Hopkins, Cushing at age thirty-three became an associate in charge of neurological surgery. He continued his work with trigeminal neuralgia and began to operate on patients with brain tumors, but with little success. It was often impossible to localize the tumor and hemorrhage was a major problem. He also became interested in diseases related to the pituitary gland and in the laboratory worked out a surgical approach to the pituitary. He would often spend all day in the operating room and then work in the laboratory at night. Within the next seven years, he would become the world’s authority on trigeminal neuralgia, brain tumors, and diseases of the pituitary.

In addition to this strenuous load of clinical and laboratory work, Cushing found time to do literary work. He became fast friends with William Osler, with whom he shared interests in literature and medical history. Cushing published many papers and book chapters on his work, to spread knowledge and to enhance his reputation.

In 1910, he removed a para-sagittal meningioma from General Leonard Wood, who had been Theodore Roosevelt’s commanding officer at the battle of San Juan Hill and later was the governor of the Moro Province during the Philippine insurrection. In 1904, while still in the Philippines, Wood had a seizure and left-sided weakness. A prominent Boston surgeon had excised a part Wood’s brain tumor but the symptoms recurred. Cushing, reluctantly and aware of the danger, agreed to operate. He encountered severe bleeding and stopped the operation. Four days later, under local anesthesia, he completed the removal of the tumor. General Wood recovered but in 1927 had another recurrence. Cushing again operated, but there was profuse hemorrhage and Wood did not survive. Cushing blamed himself for the failure.4

Cushing was a perfectionist who shaved the patient’s head, positioned the patient, and attended to every detail of the operation. He continually honed his diagnostic ability and learned from his mistakes. In 1912, Harvard invited Cushing to be the first chief of surgery at the new Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. There were delays in building the hospital and Cushing clashed with Harvard and the hospital directors over staffing and hospital organization. When the hospital finally opened, he continued his intense surgical work with brain tumors and the pituitary gland.

The outbreak of war in Europe interrupted Cushing’s work. In 1915 he went to France with the Harvard Unit of the American Ambulance Corps. These were field hospitals staffed entirely by American university doctors. The Harvard unit took over a 160 bed hospital and treated soldiers with terrible war wounds. Cushing mainly operated on head injuries but worked on facial and extremity wounds as well.

The surgeons worked in a rat-infested, muddy tent hospital, but Cushing learned war surgery. He was the first to use a magnet to remove shrapnel deep within the brain.

After his tour of duty with the Harvard Unit, he returned to Boston and resumed a heavy surgical schedule. Anticipating America’s entry into the war, he worked with politicians and the army to obtain proper medical stores and equipment and to organize hospitals to care for the wounded. Cushing had little use for bureaucracy and was often at odds with the authorities.

In 1917, when the United States declared war on Germany, the first Americans to arrive in France were the volunteer doctors, nurses, and auxiliary personnel of base hospitals four and five, organized by Dr. George Crile of Cleveland and Harvey Cushing. The Harvard unit replaced a British tent hospital in a miserable, muddy field. They had a few surgical instruments but little else. Cushing went around official channels to obtain medical equipment and ambulances. He also visited aid stations near the front and more than once was forced to dive into shell holes to avoid enemy fire. He operated on head wounds, taught other surgeons, and engaged in research involving early debridement of wounds, antisepsis, trench foot, and blood transfusion. As a result of this research, the mortality from penetrating wounds dropped from 56 to 25 percent.

During one battle, his hospital took in 200 casualties and after the third battle of Ypres he operated from early morning until two am the next day. In one day, he operated on eight soldiers with head wounds, often by the light of a candle while wearing muddy boots. Sadly, several of his patients developed gas gangrene in their wounds. In a pithy statement, he said, “Yesterday’s head has gas.”

In one of the great tragedies of the war, Revere, the son of Sir William Osler and the great-great-grandson of Paul Revere, was wounded by a shrapnel. He was taken to an American field hospital, where Cushing and other American surgeons operated on his intestinal perforations. Despite their best efforts and a blood transfusion, Revere Osler died.

Cushing was critical of the British for their indolence and of the Americans for the lack military medical preparedness. Some hospital equipment dated to the Spanish-American War or even the Civil War. The army came close to reprimanding or court-martialing him, ostensibly for security reasons.5

The army promoted him from major to lieutenant colonel and as the Americans prepared for battle, he was busy inspecting hospitals and equipment and training young surgeons. Throughout his military experience, he kept a diary, recording details of life on the battlefield, meals, visits to the front lines, and case histories of every patient he operated upon.6

During the Argonne offensive, Cushing was demonstrating how to operate on a “head case” but was forced to quit when he had double vision. Later he developed a fever with weakness and numbness in his legs and arms. He was unable to button his shirt or walk. He gradually recovered from what was either complications related to the flu epidemic or a variety of Guillen-Barre syndrome. He described himself as a “sick puppy dog” and was afraid he would not be able to operate again.

When the war ended, Cushing wrote a history of Harvard’s base hospital, which had handled 45,000 sick or wounded soldiers. He did not leave for home until February, nearly four months after the end of the war.

Harvey Cushing had reached middle age and was in poor health when in 1919 he reassembled his surgical team at the Brigham Hospital. He tired easily and was unsteady on his feet but took up a heavy surgical load. He operated on an increasing numbers of patients with brain tumors, with ever-improving results. He invented silver clips and with a physicist, W.T. Bovie, developed electrocautery for hemostasis that allowed him to remove vascularized tumors from deep in the brain.

In addition to his surgical work, Cushing had a prodigious output of books and articles not only on neurosurgery but his thoughts on medical education and practice. He sought a balance between science and the art of medicine. In a 1926 graduation address at Jefferson Medical School, he said, “If a doctor’s life be not a divine vocation, then nothing is a vocation and nothing is divine.”7

He was in constant demand as a speaker and in 1922-23 was president of the American College of Surgeons. His main duty was to give the annual oration. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his two-volume biography of Sir William Osler in 1925.

A heavy smoker, he had progressively severe pain in his feet and legs that led to gangrenous toes and hospitalization. In 1931 he left his hospital bed with gangrenous toes and operated upon his 2,000th brain tumor. The next year, at age sixty-three, he stepped down from his position as surgeon-in-chief at the Brigham Hospital and after finishing research on the pituitary returned to Yale as a professor of neurology. He had more gangrenous toes and severe pain in his feet, which improved when he quit smoking. He died in 1939 from a myocardial infarction.

One of his residents summed up Cushing’s attitude towards medicine: “This Lesson, he taught me, that no one has any right to undertake the care of any patient unless he is willing to give that patient all of the time and thought that is necessary and of which he is capable.”

One of his serious imperfections was meanness to his assistants, but then he did not hold a grudge. He was jealous of competitors, especially in matters of priority, but he wrote letters of congratulations when his former students excelled. He was kind and sympathetic with patients and personally changed dressings. He would clean patients and change bedpans.

Unfortunately, his single-minded devotion to surgery estranged him from his family. He was separated from his wife and children for long periods of time and when he was home spent time in study and writing. He did take the time to do appendectomies on two of his children and removed a tubercular lymph node from another. His oldest son died in an alcohol-related car crash; another son flunked out of Yale. One of his daughters married a son of Franklin Roosevelt. The marriages of his three daughters all ended in divorce. During his last years, Cushing was often alone and in poor health.

What made Cushing a great surgeon? He came from a medical family, he had near perfect hand-eye coordination, and he was determined to win. He was a careful, meticulous technician. He was curious about all things, could ignore fatigue, and was driven. Above all, Harvey Cushing was a humanist who put his patients first above all else in his life.

References

- Fulton, J.F., “Harvey Cushing, A Biography”; Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Springfield, Ill., 1946 pgs. 69-70

- Harvey, S.C., The Story of Harvey Cushing’s Appendix; Surgery, vol. 32, #1, September, 1952, pgs. 501-514

- Bliss, M. “Harvey Cushing, A Life in Surgery”, University of Toronto Press, 2005

- Ljunggren,B. The Case of General Wood; Journal of Neurosurgery, Vol. 56, issue 4, 1982, pg. 471

- Carey, M.E., Major Harvey Cushing’s Difficulties with the British and American Armies During World War I. Journal of Neurosurgery, 2014, Vol. 121, [2] August, 319-327

- Cushing, H. From a Surgeon’s Journal, 1915-1918; Little Brown and Co. Boston, 1936

- Loc Cit, Bliss, pg. 416

Author’s note: The biography of Harvey Cushing by Michael Bliss is an easy to read, beautifully written, outstanding example of medical biography. I recommend it to anyone with an interest in the history of medicine during the early years of the 20th century.

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, was a surgeon in chief at the Children’s Memorial Hospital and a professor of surgery at Northwestern University. After retiring from active practice, he sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and back on a 43-foot sailboat. He then volunteered at the Cook County Hospital during the transition from the old Children’s Hospital to the new Stroger hospital. He then turned to writing medical history and fiction. He now makes walking sticks for friends. Thus, his latest title is SSSS, [surgeon, sailor, scribbler, stick carver].

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 4 – Fall 2020

Leave a Reply