Göran Wettrell

Lund, Sweden

|

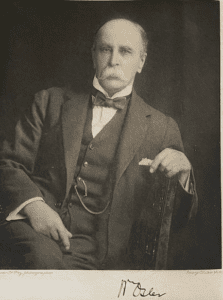

| Figure 1. Sir William Osler in Oxford, photo presented by Lady Osler. |

Sir William Osler has been described as one of the greatest physicians of his time, especially known for his bedside medicine and teaching (Figure 1). He has also been characterized as “a pediatric-minded worker within the widespread wine-yard of internal medicine.” As one of the founders of the American Pediatric Society and its fourth president, his inaugural speech in 1892 titled “Remarks on specialism” pointed out the risks of specialization and emphasized the value of a holistic view of medicine. He saw the pediatrician “as the vestigial remnant of what was formerly the general practitioner”1 and argued that pediatrics should remain part of general practice, a stance that probably contributed to the delay of pediatrics emerging as its own specialty. A few years later, when he was a ”Chief” and professor of internal medicine at Johns Hopkins University, he created a position for a clinical professor in pediatrics to work mainly in an outpatient clinic.

In his lifetime Osler published around 1,200 titles, including about 100 articles on pediatric topics.2 He published less about pediatrics in the latter part of his life, but as Regius Professor at Oxford he took care of children and teenagers from the English upper class and the Royal Family.

Osler began his academic career at McGill University in 1874, where he worked for ten years as professor, clinician, and pathologist at the Montreal General Hospital. He performed hundreds of autopsies, collected interesting specimens of congenital heart defects, and wrote careful and complete post-mortem reports. His experience performing autopsies laid the foundation for his brilliant career as a clinician. He expressed his work model as: “Observe, record, tabulate, communicate. Use your five senses. Learn to see, learn to hear, learn to feel, learn to smell, and know that by practice alone you can become an expert.”

He was appointed professor in clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 1884. During this time he was invited to give lectures in cardiology on subjects such as malignant endocarditis (London, Gulstonian lecture, Figure 2) based on impressive autopsy findings, and an important survey of bicuspid aortic valves.3 He also worked at a pediatric hospital, the Infirmary for Nervous Diseases, where he studied brain damage and neurological and muscular diseases. Based on five lectures given at the hospital, he published a study of 150 pediatric patients with cerebral paresis (Figure 3) carefully classified according to etiology and symptoms.2 He was interested in movement disorders and published articles on chorea, as well as a chapter in a pediatric textbook titled “Congenital affections of the heart.”

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Title-page of Osler’s important series of public addresses | Figure 3. Facsimile of the title-page of Cerebral Paresis of Children by Osler, 1889. | Figure 4. Title-page of The Principles and Practice of Medicine by Osler, third edition, 1898 |

When the newly-founded Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore opened in 1889, William Osler became the first head of medicine. In 1892, his most important work was published, the medical textbook The Principles and Practice of Medicine (Figure 4). About one-tenth of the book was devoted to disorders and illnesses that primarily affected infants and children.2 His emphasis on the paucity of effective treatments for many diseases was noticed by a clergyman and adviser to the philanthropist and capitalist John D. Rockefeller. In 1901 the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research was established.

|

| Figure 5. Osler observing the patient at the bedside, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore. |

The clear, concise presentation and many citations in Osler’s textbook made it unique. The one area where it lacked substance was in the details and dosages of therapeutic regimens. Osler was aware of the prevailing limitations in making diagnoses and prescribing treatments, as expressed in his quote: “Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability.” He was also skeptical of non-evidence-based therapy, stating, “One of the first duties of the physician is to educate the masses not to take medicine,” and “Remember how much you do not know. Do not pour strange medicine into your patients.” Osler instead expressed how important it was for a physician to “not only treat the disease but to treat the patient with the disease” and emphasized trust and faith in the physician as being more potent than many drugs.3

From the memorials to Sir William Osler published by Maude E. Abbott (1926) and Harvey Cushing (1928), it is evident that patients, colleagues, students, and friends were fascinated by his personality, encouragement, generosity, and personal charm (Figure 5). He also had a wide base of medical knowledge, great wisdom, and was generous with those gifts.3, 4 He demanded three things of professors—enthusiasm, full personal knowledge of a subject area, and a sense of obligation to students—all qualities that he himself exemplified.

Osler’s early work in Montreal provided many interesting specimens of congenital heart defects that are now in the McGill Pathology Museum. In 1889, Osler came into contact with Maude E. Abbott, one of the “grand old ladies” of pediatric cardiology, who was starting to catalogue and classify this collection and correlate the clinical data with autopsy findings.5 Osler supported and encouraged her work, and in 1905 invited her to write a chapter on congenital cardiac diseases in his multi-volume work Modern Medicine, 1908.

Before leaving the U.S. in 1905, Osler expressed his thanks to the medical profession at a farewell dinner and declared his three personal ideals. The first was to do the day’s work well and not to bother about tomorrow; the second, to act in accordance with the Golden Rule towards colleagues and patients; and the third, to cultivate a measure of equanimity in order to bear success with humility, the affection of friends without pride, and to greet sorrow and grief with courage.3 Sir William Osler dedicated his life to the pursuit of science, the art of teaching, and the good of humanity. His noble work is exemplified in his quote: “We are here to add what we can to life, not to get what we can from life.”

References

- Cushing, H. The life of Sir William Osler. London. New York. Toronto. Oxford University Press. 1940, volume 1 and 2.

- Osler, W. Cerebral Palsies of Children. Classics in Developmental Medicine No 1. Oxford. Blackwell Scientific Publications Ltd. 1987, 1-92.

- Sir William Osler. Memorial Volume. Bulletin No IX of the International Association of Medical Museums. Maude Abbott editor. Toronto. Murray Printing Co, 1926.

- Cushing H. Consecratio Medici. Sir William Osler, the man. Boston. Little, Brown and Company. 1940, 97-117.

- Wettrell, G. Maude Abbott and the early rise of pediatric cardiology. Hektoen International, A Journal of Medical Humanities. Section; Cardiology, Winter, 2016.

Note: All photos from the author’s copy of books in references 2 and 3.

GÖRAN WETTRELL, MD, PhD, FLS, is an Associate Professor and Senior Consultant in Pediatric Cardiology and Pediatrics at Lund University, Sweden, with interests in molecular genetics and primary arrhythmias. His other interests are male choir singing, travel, and medical humanities.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply