Julius P. Bonello,

George E. Tsourdinis

Peoria, Illinois, United States

|

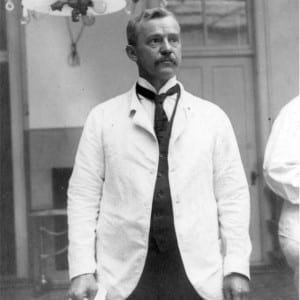

| Figure 1. Dr. Howard Kelly (Photo courtesy of The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions)3 |

Once dubbed the “Prince of Gynecology,” Dr. Howard A. Kelly was one of the most prominent surgeons in the United States in the early twentieth century.1 Through the blessing of Sir William Osler, Kelly had risen to the rank of Head of Gynecology at Johns Hopkins Medical School at the height of his career.2 Among his many contributions to gynecology and surgery, Kelly’s legacy lives on in his creation of an autopsy technique that circumvents incising the abdominal and thoracic cavities.

Kelly was born on February 20, 1858 in Camden, New Jersey. After the Civil War his family relocated to Philadelphia, where he pursued general studies at the Classic Institute of Dr. John W. Fares and obtained a degree in arts at the University of Pennsylvania. Thereafter, he attended his alma mater’s medical school, studying under such renowned physicians as Pancoast, Penrose, Goodell, and Wood. It was not until his third year that he began to suffer severe bouts of insomnia, prompting him to take a leave of absence to work as a ranch hand and cowboy in Colorado in 1882. Returning with improved health to Philadelphia, Kelly completed his medical training and was awarded his Doctorate of Medicine in 1882. He served his medical internship at the Episcopal Hospital in Kensington, a working-class district of Philadelphia. It was during his internship that he caught the attention of Sir William Osler after publishing his article “On a Method of Post-Mortem Examination of the Thoracic and Abdominal Viscera Through Vagina, Perineum, and Rectum and Without Incision of the Abdominal Parietes.”

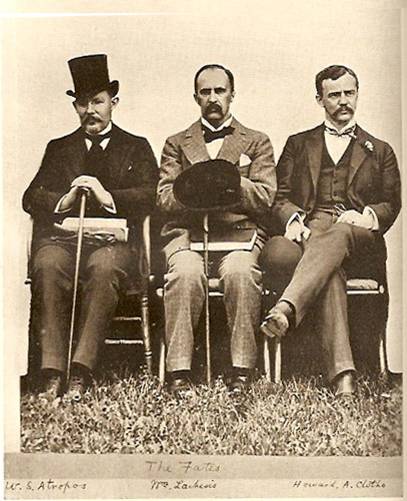

Following his internship, he returned to the Kensington area of Philadelphia among the steelworkers whom he had known throughout his earlier years. After three years of practice, his interest narrowed to surgery and gynecology. Realizing the need for a hospital devoted solely to gynecology, he founded the Kensington Hospital for Women in 1887, the sixth women’s hospital in the United States. Concurrently, William Osler moved from Montreal and accepted a position in Philadelphia at the University of Pennsylvania. Fond of Kelly after reading about his novel autopsy method, Osler often visited Kelly to watch him operate and reportedly remarked that he had never seen a more skilled surgeon. Osler offered him a position at the University of Pennsylvania as assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, which Kelly accepted. Simultaneously, Johns Hopkins, a wealthy philanthropist, wished to establish a university and hospital in Baltimore. In 1884 this wish came to fruition with the appointment of William Osler as Head of Medicine and William Halstead as Head of Surgery. With his newfound influence over the Hopkins trustees, Osler insisted that Kelly be offered the position of Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Kelly reluctantly accepted the position, for he had misgivings about a combined Obstetrics and Gynecology Department. When Johns Hopkins Medical School began in 1893, the trustees agreed to develop a separate Department of Obstetrics headed by John W. Williams.

During his years of service in Baltimore, Kelly devised a number of gynecologic operations and instruments. Among his discoveries were the aeroscopic method of cystoscopy and the creation of the eponymous “Kelly” clamp, a ubiquitously used surgical instrument. He first introduced into common practice the examination of the air-distended rectum in the knee-chest position using a scope he designed himself.

In addition to his surgical prowess, Dr. Kelly was a pioneer in the radical surgical treatment of cancers of the uterus by radiation. In the fall of 1892, he opened a private clinic, which was later incorporated in 1913 as the Howard A. Kelly Hospital. Here, his use of radiotherapy continued until the 1940s. Kelly’s technique was notable for being one of the first to exclusively use radium for treatment. For years the Kelly Hospital had administered all of the radiation for patients at Johns Hopkins and most of the radiotherapy in Baltimore and the state of Maryland. According to one biographer, Kelly was said to have received from his private patients the largest fees of any surgeon in the country. He often opined that a physician of experience and skills should command large fees when feasible, to give both time and service to the poor to whom he would submit no bill. Another interest of Kelly’s that came to fruition under his direction was a medical illustration department that began in the early 1900s. With the help of this department, he authored or coauthored over 200 articles and fifteen books over the next thirty years. Finally, as a true women’s advocate, he preached against the prejudicial treatment of women in medicine and championed their increased role as physicians and nurses. He retired after thirty years as Head of the Department of Gynecology at Johns Hopkins. In his lifetime, Kelly received numerous honors and awards, including five honorary doctorates. He died in 1943.

|

| Figure 2. (left to right) Dr. William Stewart Halsted, Dr. William Osler, and Dr. Howard Kelly (Photo courtesy of The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions) |

It is no surprise to the modern physician that a surgeon such as Kelly, who specialized in operations of the pelvis, would develop a minimally invasive method via pelvic anatomy for inconspicuously accessing internal organs post mortem. In this seminal case series Kelly described an alternative autopsy method of retrieving organs for examination per vaginam, per rectum, and per perineum. He described his rationale for developing this new method: “It is often a source of great disappointment to physicians to be unable to secure autopsies in obscure cases, on account of the unwillingness of relations and friends to permit any ‘mutilation’ of the body. In a large proportion of such cases the difficulty may be met, and a satisfactory autopsy secured by the method described in this paper, which I have now practiced in five cases.”4

His first case was that of “a powerful Irishman aged thirty-two years, who died in the Episcopal Hospital of right apex pneumonia.” The patient’s friends had refused any obvious “disturbance” of the patient’s body, so Kelly opted for a method that “should not make any visible mutilation of the body.” Cutting from the “penoscrotal junction to the margin of the anus and down to the bulb,” Kelly was able to work his hand through into the pelvic and abdominal cavities without injuring the bladder or rectum. Advancing his arm until his shoulder was engulfed by the body cavity, he palpated the free border of the liver and—with difficulty—pierced through the diaphragm, allowing him to remove the lungs and heart for examination.

Another case was that of a “fine-looking, well-formed Irish girl of twenty-two . . . was brought to the hospital in a condition of extreme anasarca, from which she shortly afterward died.” A per vaginam autopsy was made here, allowing Kelly to access the abdominal cavity and remove two enlarged kidneys. In keeping with his promise, “the vagina was packed with cotton and the body replaced in the coffin, bearing no marks which could suggest a disturbance of the remains.”

The last case he outlined involved “a man twenty years of age, who died in the ward in consequence of large pleuritic effusion and complete splenization of the right lung . . . and marked pericarditis.” Kelly successfully attempted an autopsy per rectum, washing out the gut and accessing the abdomen via an incision in the rectal vault. The thoracic contents were successfully removed for examination, but compared to his prior two methods, the incision was “a far more conspicuous object than the closed perineal wound well concealed by the legs and scrotum.”

Kelly’s legacy continues to live on in modern adaptations of his procedures. Knowledge of this novel method motivated Bonello et al. to perform a hand-assisted laparoscopic resection of a carcinoma of the rectum that followed in true Kelly-esque fashion. Just as Dr. Kelly extracted intrathoracic and abdominal organs via a perineal incision, so too were Bonello and colleagues able to remove the rectum similarly while minimizing the invasiveness of the procedure.5

Finally, it is imperative to note that Kelly’s novel idea did not come without ethical concern by modern standards. He often performed these autopsies oblivious to universal precautions and without obtaining informed consent from the family of the deceased. However, the true message of this article is not to promote his reckless abandonment of autopsy decorum, but rather to underscore his relentless drive to seek out the cause of his patients’ demise. Necessity begets inventiveness, and thus created Kelly’s unorthodox procedure. The next time you find yourself assisting in a surgery or operating, and request or hand over a “Kelly,” coursing through that clamp’s name is the history of a compassionate physician, an adept surgeon, and a champion of women’s rights, who endeavored to better his patients’ lives—even if it meant doing so through alternative routes.

References

- Kelly, Howard A. “Pre-1933 History of Gynecology in Maryland. Part 2.” Maryland State Medical Journal 29, no. 7 (July 1980): 21–30.

- Allen, P M, and T K Setze. “Howard Atwood Kelly (1858-1943): His Life and His Enduring Legacy.” Southern Medical Journal 84, no. 3 (March 1991): 361–68.

- Davis, Audrey W. Dr. Kelly Of Hopkins: Surgeon, Scientist, Christian. 1st ed. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1959.

- Kelly, Howard A. “On a Method of Post-Mortem Examination of the Thoracic and Abdominal Viscera Through Vagina, Perineum, and Rectum and Without Incision of the Abdominal Parietes.” The Medical News 42, no. 26 (1883): 733–34.

- Dodson, R W, M J Cullado, L E Tangen, and J C Bonello. “ Laparoscopic Assisted Abdominoperineal Resection.” Contemporary Surgery 42, no. 1 (1993): 42–44.

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions for the use of their photographic material.

JULIUS P. BONELLO, MD, FACS, has taught students and residents for the last forty years at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. He now holds the title of Professor Emeritus of Clinical Surgery. He has eight children and lives in Peoria IL with his wife of thirty years.

GEORGE E. TSOURDINIS is from Chicago, IL and received his undergraduate degree in Biological Sciences from The University of Chicago in 2017. He currently attends the University of Illinois College of Medicine in Peoria, IL as a third-year medical student and intends to pursue a career in Internal Medicine. His research interests include Alzheimer’s disease, the history of medicine, and bioethics.

Winter 2020 | Sections | Surgery

Leave a Reply