Migel Jayasinghe

England, UK

This article was previously published by the author between the years of 2006 and 2018. The original publisher has since been lost and the article edited and republished by Hektoen International staff. Other appearances of this text elsewhere on the internet may be unauthorized.

|

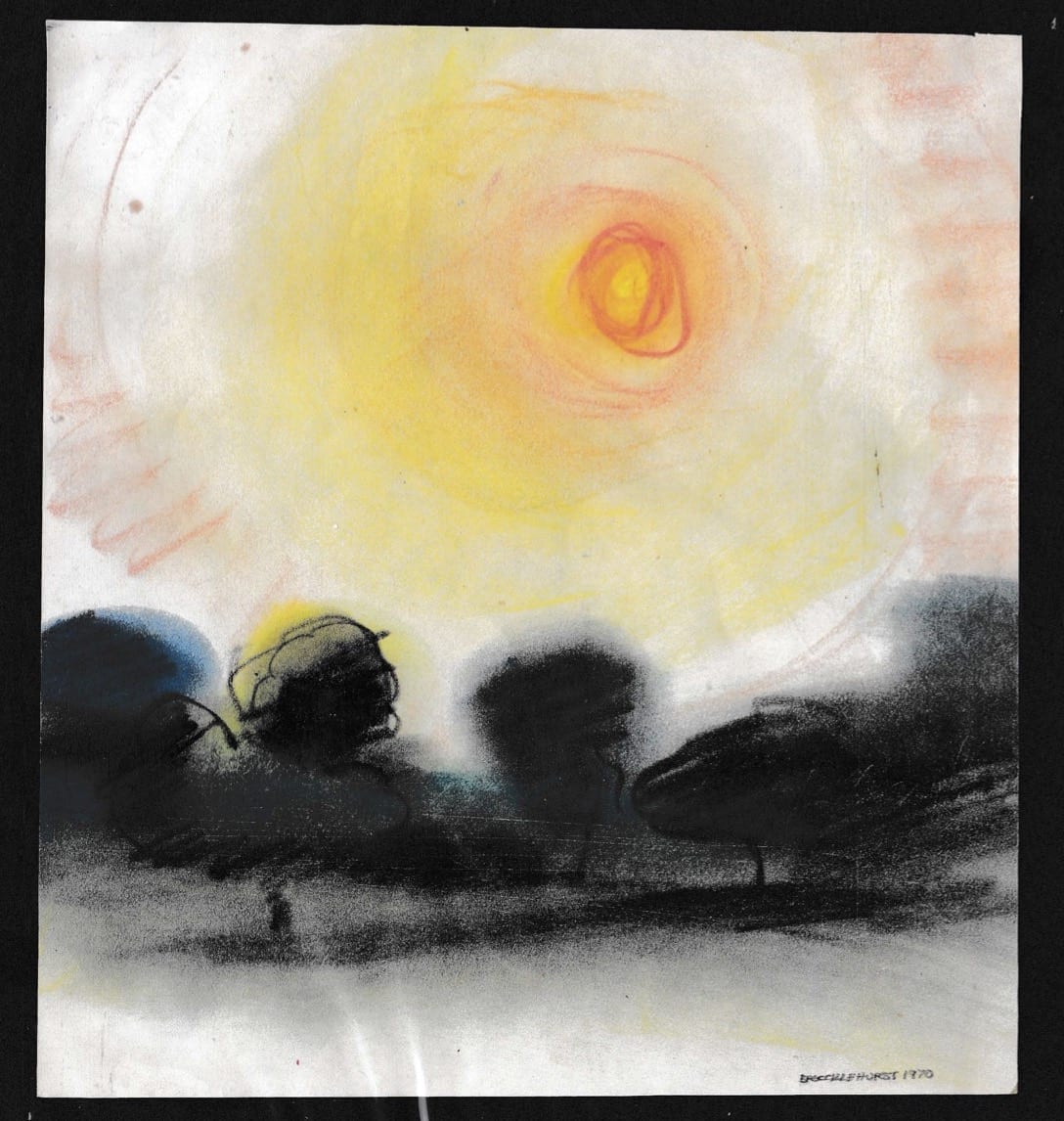

| Hampstead Heath, 1970 by Jo Brocklehurst. |

The British Association of Counselling defines counseling as “an intervention in which one person offers another time, attention and respect, with the intention of helping that person to discover and clarify new ways of living more resourcefully and towards greater well-being” (1984). Note that there is no requirement for the helper to belong to any designated profession or position, such as doctor, psychologist, priest, or elder. However, that begs the question whether anybody can undertake counseling and be effective.

To answer the question, let us go back to the antecedents of counseling. Traditionally, people suffering from extreme abnormalities in thought and behavior were seen as mentally ill and either isolated or treated by psychiatrists. However, most of those identified as suffering from some type of mental disorder did not require hospitalization or drug treatment throughout their recovery phase. What they needed was psychotherapy, described as “talking cures,” where characteristically, psychoanalysis held sway during the early part of the twentieth century until behavioral and cognitive therapies became more prevalent.

Increasingly, psychoanalysis could not be justified on scientific grounds or by the cost and length of treatment. It gave way to cognitive behavioral therapies modeled on learning theory based on Pavlovian classical conditioning and Skinnerian operant conditioning. Those who needed such psychotherapeutic interventions were “patients,” and those who treated them were drawn from the medical profession. In addition to psychiatrists, clinical psychologists in hospital settings also became providers in the care of such patients.

Counseling evolved as an intervention outside the medical context offered by practitioners, with thought drawn from disciplines other than strictly the medical establishment. An inability to cope with an ordinary life increasingly devoid of traditional support mechanisms like family, church (orthodox religion), and community, mostly in advanced industrialized societies, left a growing populace vulnerable to psychological stress. Counseling, therefore, happens to be a much broader concept than psychotherapy that evolved from existential, philosophical, and humanistic concerns. Those seeking help from counselors were not identified as patients. Not only were individuals seeking “greater well-being” catered for, but those seeking help in specific contexts such as career guidance and marital problems received care, meaning that there was no longer a stigma attached to counseling/therapy. Indeed, the origin of the very term counseling is ascribed to Frank Parsons (1909)1 who initiated help for young people with problems finding suitable paid employment at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Today, there is a continuum of helping interventions that range from intensive psychotherapy through counseling, to co-counseling, to life coaching, where practitioners range from medical specialists to those drawn from varied walks of life, but with appropriate and recognized counselor training. The relationship between the counselor and the counseled is one of equality. The counselor does not set themself up as an expert. The client is the expert on their self. The counselor explores options elicited during the counseling process with the counseled. By meeting at regular intervals, the counselor helps the counseled to commit to agreed-upon courses of action, gently but firmly holding them responsible for the outcome. Counseling is a burgeoning profession and the recognition afforded its mainstream practitioners is a testament to its enduring value.

It is necessary to look more closely at the theoretical underpinnings of the practice of counseling. A recent analysis of the relationship between counseling and theory referred to more than 130 extant theories of counseling. However, most reviewers of the literature posit three or four basic yet overarching formulations as the main approaches to counseling and therapy.2 They are psychodynamic, humanistic, (person-centered), cognitive-behavioral, and eclectic (multi-modal) approaches. There is also the growing conviction that therapists from varied backgrounds and theoretical orientations are very similar in their conceptualizations of the ideal therapeutic practice and outcomes. In the following paragraphs, the humanistic person-centered approach to counseling is more closely examined.

Carl Rogers, the founder of the Person-Centred Approach (PCA), adopted the term counselor to refer to himself when he formed the Association of Humanistic Psychology in 1961. As a reaction to the mechanistic approach to human lives from behavioristic and psychoanalytical approaches, the humanists dedicated themselves to a psychology focusing on uniquely human issues. Some of the terms that came into use were “self,” “self-actualization,” “health,” “hope,” “love,” “creativity,” “nature,” “being,” “becoming,” “individuality,” and “meaning.” Awarded recognition by the American Psychological Association (APA) as its Division 32, humanistic psychological counseling began for the first time using the term “clients” for those who used their services instead of “patients.” Carl Roger’s 1951 book Client-Centred Therapy showed the way for others like Fritz Perls who developed Gestalt therapy from a humanistic orientation.3

Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow were among the founders of the Human Potential Movement, which was influenced by existentialist philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Sartre. Their credo could be summarized by the sentence: “Man’s wholeness is to be sought through direct experience rather than analytical reflection.” This perspective challenged the Freudian psychoanalytical view that man was at the mercy of his unconscious drives and instincts; it was also in opposition to the view of the behaviorists that man was at the mercy of his environment and learned behaviors.

A defining moment in the life of Carl Rogers was when as a boy growing up on a farm he came across some potatoes thrown into a darkened basement room. They were left there to rot, but where there was a chink of light coming through from the outside in a corner of the basement, he found a couple of near-rotten potatoes thrusting shoots towards the light. In spite of all the odds they were growing! He later wrote that here he had discovered a fundamental actualizing tendency that is inherent in all organisms, a basic drive towards wholeness of the organism and an actualization of its potentialities. He extrapolated this self-actualizing tendency to human beings in whom he believed it to be a non-conscious organismic function which, when in conflict with conscious awareness and the external environment, tended to create conditions for mental and physical distress.

Rogers stated that when an individual seeks help from a counselor, the latter creates an environment or relationship hitherto denied to the client which is conducive to growth. The counselor facilitates change using skills in communication, in understanding, and by modeling an alternative way of being. He postulated three interrelated counselor competencies as crucial to the success of person-centered therapy. These were congruence, unconditional positive regard, and empathy. He later added a fourth dimension, that of “tenderness.”

Congruence refers to the counselor being open and genuine—a willingness to relate to and engage with clients without hiding behind a mask or professional facade. Unconditional positive regard occurs when the counselor accepts the client wholeheartedly by listening to the client without interrupting, judging, commenting, or giving advice. The counselor does not show disapproval of, or tend to evaluate, any particular feelings, actions, or characteristics of the client. He does not seek to censor the client in any way. The counselor totally accepts the client for who they are.

Empathy is shown when the counselor appreciates the client and their situation from the client’s point of view. The counselor reacts to the client’s feelings with sensitivity and with emotional understanding. Empathy alone is sufficient in many instances to bring about a positive therapeutic transformation in the client. Person-centered counseling/therapy is a non-directive approach where the client is free to explore issues most important to them without being subjected to direct advice or any coercion by the counselor.

The last condition required from the person-centered approach, tenderness, is a spiritual or intuitive way of relating to human beings. It is said to be a self-giving mode of love known to the Greeks as agape. Rogers believed that “profound healing and growth takes place when the counsellor conveys such a cognitive-affective, non-verbal, transcendent and spiritual loving/knowing of the client.”3

The ultimate aim of Rogerian counseling, or any counseling for that matter, is to enable the client to realize their true potential and become a “fully functioning” human being able to achieve the goals they set for themselves in life.

References

- Parsons, F. (1909) Choosing a Vocation; Houghton Mifflin & Co.

- Dryden, W. & Mytten, J. (1999) Four approaches to counselling and psychotherapy; Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

- Rogers, Carl (1980) Client-Centred Therapy; Its Current Practice Implications and Theory; London Constable.

MIGEL JAYASINGHE, BA (Hons), M.Sc., AFBPsS, C.Psychol., was born in Ceylon, (Sri Lanka) and migrated to the United Kingdom in 1963 at age twenty-six. Migel acquired a BA (Hons) in Psychology from London University Goldsmiths College, worked as a research assistant at Industrial Training Research Unit, Cambridge (1973–1974), and served as an occupational psychologist at Educational and Occupational Assessment Service in Lusaka, Zambia (1975–1978). Migel gained a M.Sc. in occupational psychology from London University Birkbeck College (1981–1982), began as an occupational psychologist, and was promoted to higher psychologist with the Manpower Services Commission, UK. Migel worked mainly at two Employment Rehabilitation Centres (1981–1995) and was a senior occupational psychologist with Royal British Legion Industries before retirement (1996–2001).

Spring 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply