Stephen Martin

Durham, UK & Thailand

|

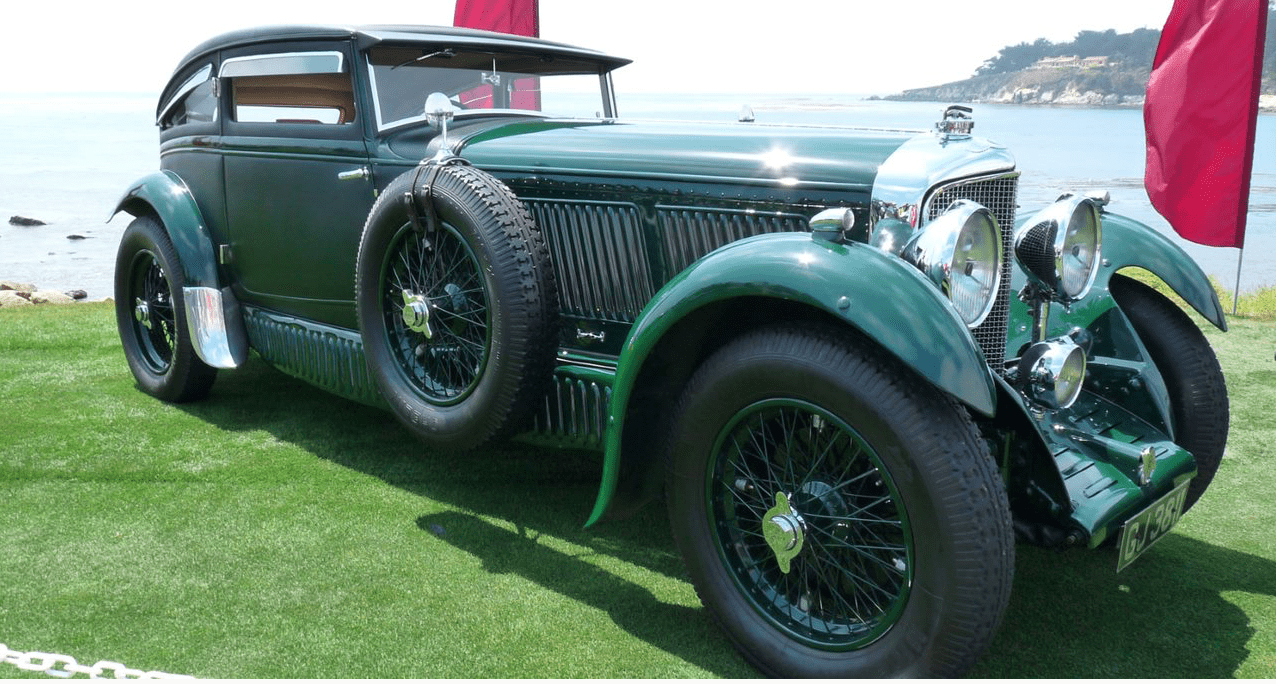

| Fig 1. Bentley Speed Six. Source: Craig Howell, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia |

In 1926 my grandfather started work for Dr. A.S. Robinson in Redcar, a small town on the Yorkshire coast. The doctor needed a driver—at least that was the plan at first. He sent him for a fortnight to the Rolls Royce School of Motoring at Hendon, on the old Handley-Page factory airfield. He returned a fully-trained chauffeur and was given a cap, a uniform, and the keys to the latest 6.5 litre Bentley at age sixteen. (Fig 1) There was no driving license then and it could, in an emergency, become a 100-mile-an-hour supercar. Dr. Robinson kept him in check, though, saying, “Always heed this golden rule: Round the corner lurks a fool.”

Driving the good surgeon around to see his patients, he was quickly roped into nursing duties, supervised by his boss, and all perfectly legal. He assisted with surgeries and anesthesia, typically gallbladder and appendix operations, as well as performing wound care and setting fractures.

Early years

Dr. Robinson was fortunate to be born into an affluent Leeds family. His father ran a stoneware bottle factory. They could afford a maid1 and for Alfred to study medicine at Cambridge. He graduated from Emmanuel College and joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, going from student to Lieutenant in 1889.2 After service, evidently in India and Hong Kong, he set up a medical practice as a self-employed surgeon in Redcar by 1901.3 He was successful, employing a cook and a maid in his home, Dundas Villa. He also housed his widowed sister and her daughter, whom he later adopted. He was stocky and dapper, with a brown suit, large mustache, and wise expression. His surgery functioned as a small hospital. It pre-dated Redcar’s Stead Memorial Hospital and was much closer than the existing North Ormesby Hospital.

|

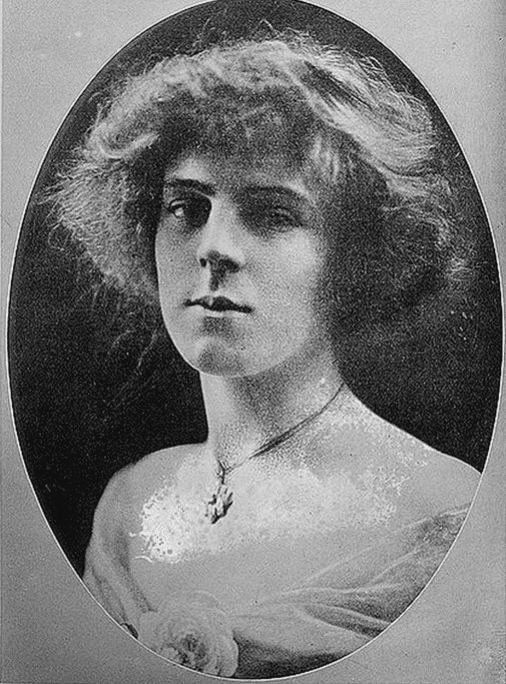

| Fig 2. Sir Hugh and Gertrude Bell, by Edward Poynter. Source: Wikimedia Commons/therountons.com US-PD |

He returned late in life to military medicine in the First World War,2 serving for most of the conflict from late 1914 on the Western Front. He was one of the first RAMC doctors attached to the Royal Flying Corps. Operating in field hospitals on injuries from crash landings was intense and high-pressure, but invaluable experience. Often in the deep end with common surgical emergencies, his personal field kit included surgical and anesthetic equipment. He did not talk about his experiences in detail after returning home.

Gertrude Bell

Dr. Robinson looked after the Bell family in Redcar. Sir Thomas Hugh Bell inherited the Teesside Ironworks. He was a decent employer, renowned for looking after his workers. His daughter, the phenomenal Gertrude, (Fig 2) was famous as a diplomat, forming the Hashemite Kingdoms of Iraq and Jordan. Her work in the Arab world and interest in archeology brought her into contact with Lawrence of Arabia. Hugh Bell was not just a client, but also a friend of the leaders of the Arts and Crafts movement. He commissioned Phillip Webb to build his house, Red Barns, in Redcar. William Morris made the Redcar Carpet (Fig 3) for Red Barns, which is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, as well as supplying the wallpaper. On occasional visits there, Dr. Robinson had the rare artistic privilege of seeing those treasures in their intended grouping.

Sir Hugh outlived his daughter, who sadly died of a barbiturate overdose in 1926. She normally took them to sleep and smoked heavily. There is a suggestion that she was diagnosed with lung cancer in her last stay in England from July to September, 1925.4 Lung cancer can cause depression and suicidality, both from distress and the chemical effects of the disease on the mind. Tumor diagnosis would have been possible with the early x-ray service when she returned home. Gertrude Bell’s house had a private railway platform halt and Park View in Middlesbrough, down the line, was at the time a pioneering x-ray clinic. Dr. Robinson could refer patients there. In the 1920s a room was fitted out with lead lining, behind floor-to-ceiling oak panels, in the radiologist’s house. It still exists, no longer for x-rays, but as a consulting room. It is a delight to enter, passing a beautiful Art Deco lamp of a lady torch bearer fixed to the stair newel.

|

| Fig 3. Design for the Redcar carpet, William Morris. Source: Wikimedia, Planet Art CD, PD |

My view is that Gertrude’s overdose was probably an accident. She wrote to her stepmother5 from Baghdad twice on the 7th of July,6 five days before she died. These letters are lengthy, detailed, spirited, and full of the enjoyment of ideas, plans, and experiences. There is nothing hypomanic about them to suggest a subsequent depressive switch. Nothing indicates that she was ever mentally ill. Other letters that year from Baghdad are similar. There is no depression in them. Accidental double-dosing in confusion does, on occasion, tragically kill. There is also a report that she asked a maid to wake her up. The lung cancer, too, is questionable with the timing of the history. At the time, three months of survival from diagnosis would have been likely, not eleven months of normal activity. There is another clue. In her letter to her stepmother on 29 September 1925,6 Gertrude noted that a friend spoke of her company at dinner: “You must be a habit, like a drug or something which one can’t do without once one has begun it.” This suggests Gertrude herself had the barbiturate issue at least in her subconscious mind.

Gertrude’s barbiturates probably came from a British Forces doctor in Baghdad, where local pharmacy was undeveloped.7 Robinson’s reputation was as a sharp diagnostician and cautious prescriber. With a modern medical conscience, he warned of risks and side effects. For modern operations today, super-specialization is practiced for safety. In some areas of medicine, breadth of experience and ability can make a better doctor. My grandfather never saw Dr. Robinson preside over any disasters. He knew his limits and did not pass them.

Esther Cleveland

Dr. Robinson also cared for Esther Bosanquet (Fig 4) and her family. She was the daughter of President Grover Cleveland and the only child of a US President to have been born in the White House. She married a Yorkshire Ironworks manager and lived most of her long life of philanthropy in the wonderful Kirkleatham Old Hall, on the outskirts of Redcar in a Carolean philanthropic development.8 Esther’s daughter was Philippa Foot, professor of philosophy at UCLA. What was it about Redcar and pioneering, successful women? You cannot help but feel that learning, decency, tolerance, and philanthropy made a liberating culture—perhaps a kind of Arts and Crafts Enlightenment. Whilst Esther’s mother had opposed women’s suffrage, Esther paid for Philippa’s education in Ascot and Oxford to break the mold of futile home tutelage. Esther bridged the attitudes of two very different generations in a way that we now know contributes so much to health and well-being.

|

| Fig 4. Esther Bosanquet, née Cleveland. Source: Bains News Service PD. Library of Congress. |

A busy character-doctor

Alfred Robinson worked hard. His many patients loved him. He wrote and lectured on history, and had a great enthusiasm for the archeology of Yorkshire of all periods. He was keen on saving lives at sea, significant in Redcar history for centuries. He supported the lifeboat crew as their doctor and fundraiser, in which he scorned wasting money on prerequisites.9 One of his lectures survives10 about the Zetland life boat. This is still preserved in the town and is the world’s oldest surviving one, built in Georgian times.11 Dr. Robinson campaigned to restore it and keep it in Redcar. When the National Maritime Museum was scratching for it, he said, “You can take it from me they won’t get it.”10 He arrived in Redcar too late to prevent the demolition of the Georgian seafront hotel where Nathaniel Hawthorne had worked on The Scarlet Letter.

In an introduction to a local history work12 with the Bell family as the main subscribers, Dr. Robinson made it plain how important it was to do educational and social work. The discovery of a Caribbean swordfish on Redcar Beach excited him: “An armed alien, which had wandered from its haunts,”13 a double metaphor, perhaps, as this was just before he returned to military medicine in France. He greatly appreciated medical humor and from his time in Asia kept up-to-date in the science of snake venom. He fully recognized the value of good writing and kept his humanities interests as a hinterland of escape. His one personal eccentricity from medical science was to sprinkle hydrochloric acid instead of malt vinegar on fried potatoes.

My grandfather was proud of his knowledge of the hepatorenal pouch of Rutherford Morrison, gleaned from Robinson’s teaching. Dr. Robinson’s love of history also rubbed off—he would trot out phrases like “Those were the days when Lister was poisoning everybody with Carbolic” and relished in telling me, as a little boy, anecdotes from his dear old boss about the worst medical smells. He assisted Dr. Robinson on occasion operating on patients’ kitchen tables. They even had a bout of fashionable, prophylactic appendectomies, requested by 1920s middle-class hypochondriacs.

|

| Fig 5. Dr. Robinson’s bomb-damaged copy of Gray’s Anatomy. Source: photo © author. Public domain for non-commercial use. |

Epilogue

Alfred’s end could not have been predicted. One evening in 1941, a Luftwaffe bomber did not do the usual raid on the ironworks, but emptied its racks over the last strip of Redcar’s suburb before the North Sea Coast. One bomb hit Dr. Robinson’s surgery, a second hit his house, and the third hit his club, where he died with many of the town’s dignitaries.

My grandparents thought a lot of Dr. Robinson, a physician with a warm heart whose interests and public-spirited activities were infectious. His surviving writings and press reports all bear that out. When my grandfather joined the volunteers clearing the bomb sites, he picked up Dr. Robinson’s well-thumbed Gray’s Anatomy with the cover blown off. (Fig 5) He also found a Mesolithic flint axe collected by him on the Moors. Like lasting memories of good works, the axe was polished, impressive, and unscathed.

References

- England and Wales Census, 2 April, 1871.

- Carey, GV (ed). The War List of the University of Cambridge, CUP, 1921.

- England and Wales Census, 5 April, 1891.

- eleanorscottarchaeology.com – under Gertrude Bell, also personal communication on gaps in the archive

- This was the writer Florence Bell, who wrote the play Alan’s Wife, anonymously, with the American suffragette Elizabeth Robins. Gertrude’s own mother died when she was three, but her letters show that she was very attached to her stepmother.

- http://gertrudebell.ncl.ac.uk/letters.php

- Al-Jumaili AA, Hussain A, Sorofman B. Pharmacy in Iraq: History, Current Status and Future Directions. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2013. 70, 368 – 372.

- https://hekint.org/2017/05/10/kirkleatham-hospital/

- Daily Mail, Hull, 9.9.31.

- Cleveland Standard, 20.3.37

- Personal communication from Royston Barker MBE, on his discovery of the Zetland shipbuilder’s plate

- Fallow TM. Ed’s Robinson A S, Batty J E. A History of an Ancient Church at Coatham. Sotheran, Redcar, 1929.

- News reports chronology, 11.10.14, via redcar.org

This article is partly based on conversations with the author’s grandfather in the 1970s and 80s.

STEPHEN MARTIN is a semi-retired neuropsychiatrist, Honorary Professor of Psychiatry at Chiang Mai University, and Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society.

Leave a Reply