Iain Macintyre

Edinburgh, Scotland

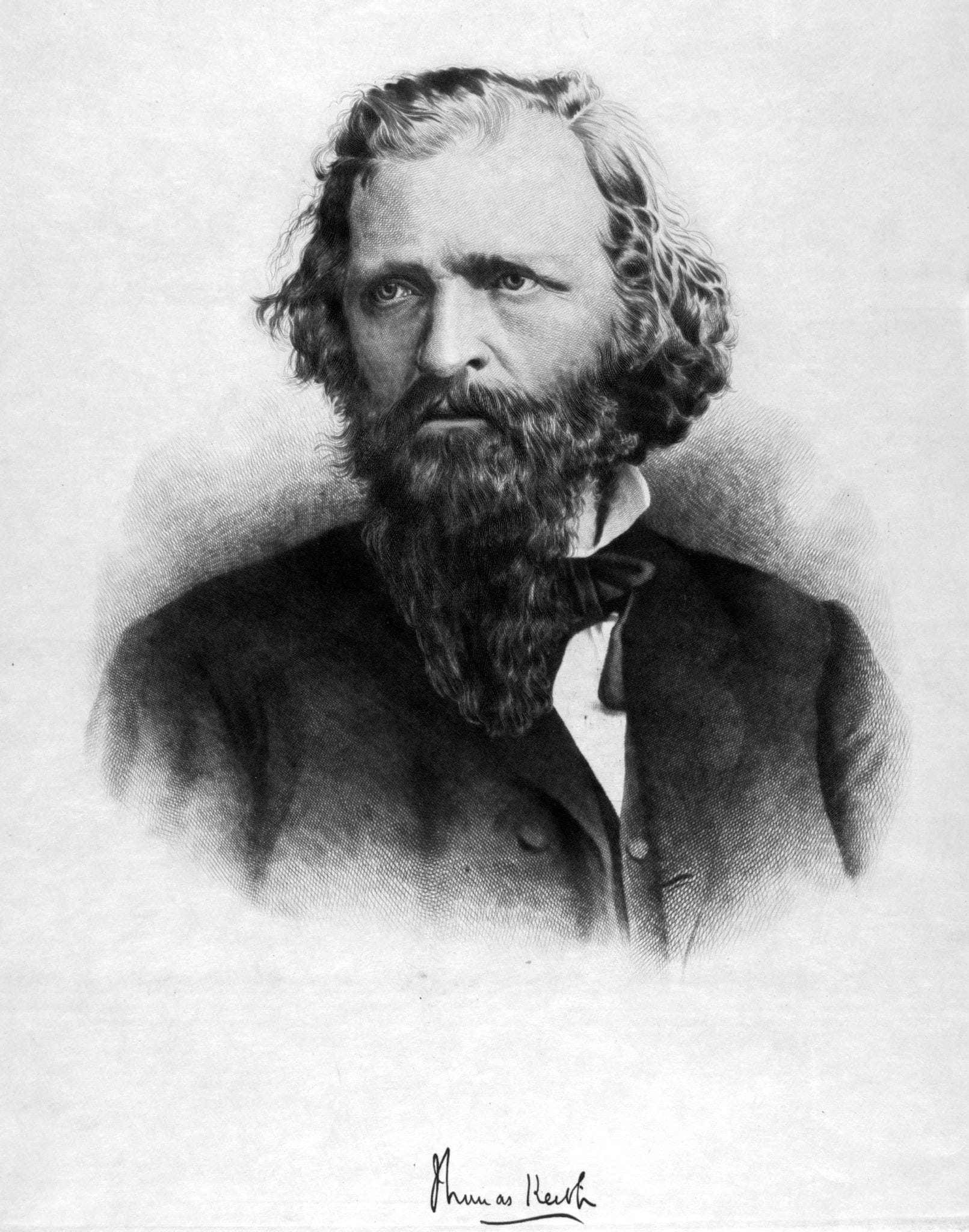

“His success so far outstripped that of all other operators, that it became a wonder and admiration of surgeons all over the world.”1 So wrote J Marion Sims (1813–1883), arguably the most famous American surgeon of the 19th century and often described as the father of surgical gynecology.2 Sims was describing the results achieved by the Scottish surgeon Thomas Keith whose published mortality rates from the dangerous and controversial operation of ovarian cystectomy were the lowest in the world. Determined to see for himself what lay behind this success, Sims crossed the Atlantic on two occasions to watch Keith operate and to discover the “secret” of his remarkable surgical outcomes. Sims’ accolade brought Keith a degree of fame, but his medical colleagues and his obituarists seemed unaware of an earlier, equally pioneering contribution in the new art and science of photography.

Thomas Keith was the son of the Rev. Dr. Alexander Keith (1792–1880) who took an early interest in photography through his friendship with the brothers Sir David (1781–1868) and Dr. James Brewster (1777–1847), both notable photographic pioneers. Moreover, in 1843 he had sat for a photographic portrait by the celebrated early photographers David Hill and Robert Adamson. In 1844 Rev. Keith traveled to the Holy Land, with his elder son George Skene Keith (1819–1910), where George took about 30 daguerreotypes of places of Biblical interest in Palestine and Syria, 18 of which were used as the basis for etchings to illustrate his father’s book Evidence of the Truth of the Christian Religion.3

In 1845 Thomas Keith became apprentice to Dr. (later Sir) James Young Simpson (1811–1870) and his obituary would describe him as the last medical apprentice in Edinburgh.4,5

After graduating MD from the University of Edinburgh he was assistant to Professor James Syme (1799–1870) and learned from him the importance of absolute cleanliness in the surgical wound, an important lesson at a time when cleanliness was not yet a feature of surgical practice. Keith also learned from Syme the value of meticulous attention to detail, particularly with hemostasis.6 Keith was succeeded as house surgeon by the young Joseph Lister (1827–1912), and the two remained friends for life. Keith went into practice with his brother George, who, with Simpson, had taken part in the famous experiment at 52 Queen Street, Edinburgh in 1847 during which the anesthetic effects of chloroform were discovered.7

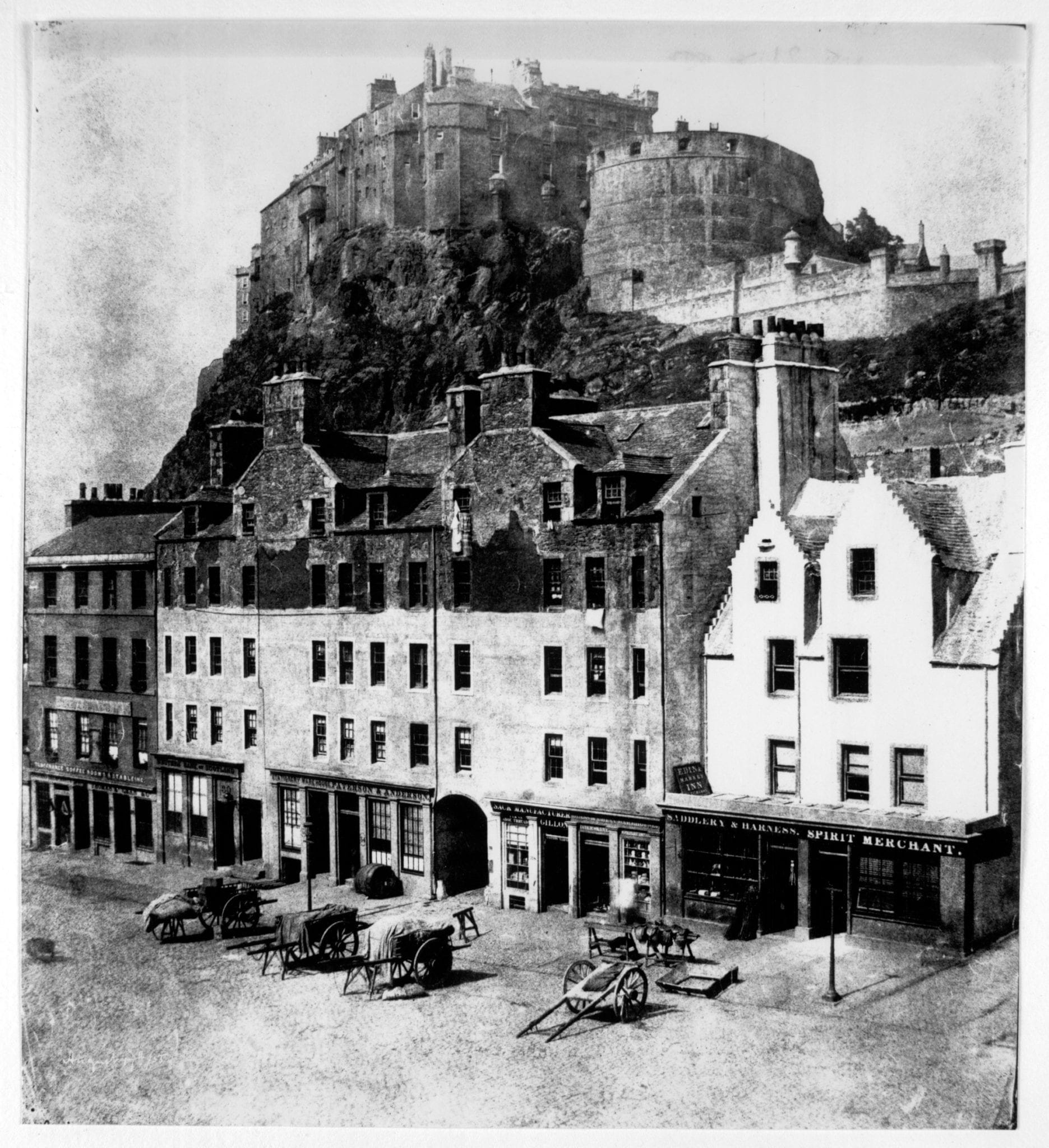

Over the years, Thomas Keith came to specialize in gynecology and in 1862 performed his first ovariotomy, but in the years 1853–1856, he devoted much of his time to photography leaving a legacy of images acclaimed both for their technical innovation and their aesthetic qualities.

Photographer

Keith simplified and improved the waxed paper technique developed by Gustave le Gray (1820–1884). This did not require the coating of heavy glass plates just before and after exposure so that the photographer did not need to rush home to process them. Keith published the details of his technique in 1856, noting that the original technique was “not suitable for our climate.” He describes various changes he tried in the chemical solutions, in timing, and in temperature, all carefully recorded along with their effects on the final image. This account shows his meticulous attention to detail and his willingness to innovate and experiment.8

Keith’s 1853–1856 photographs have been admired by photographic historians for their flair in composition and superb use of light.9

Ovariotomy

After 1856 Keith devoted himself to surgery, in particular to the new and, at that time, controversial and dangerous procedure of ovariotomy.

Ephraim McDowell (1771–1830) in Kentucky reported the first successful performance of this procedure in 1809.10 In Britain, Thomas Spencer Wells, who performed his first ovariotomy in 1857, published each of his cases in detail and robustly justified the procedure in the medical press.11 Yet the mortality rate when he published his first fifty cases in 1862 was 34%. Mainstream surgical opinion took the view that the high mortality rate did not justify performing the operation. Yet huge ovarian cysts could cause severe debility as they were invariably diagnosed at a late stage when they could weigh up to 120 lb (55 kg) and contain up to six gallons (27 L) of fluid.

Keith began to perform the procedure in 1862 keeping meticulous records from the outset. His technique paid strict attention to cleanliness and used “antiseptic dressings,” initially the tar bags used by Spencer Wells and, from 1866, carbolic solution.12

His detailed case reports in the Edinburgh Medical Journal13 were supplemented by published summaries in the Lancet of every 50 cases. This showed that his mortality rate progressively fell from 22% in the first 51 cases to 18% after 150 cases.14

This compared to mortality rates of between 30% and 34% in other contemporary published series.

Yet Keith was soon able to improve his results still further, publishing a series of 50 cases with a mortality rate of only 8%15 in marked contrast to Spencer Wells’ later series which showed a mortality of 23%.16 Keith had been taught the antiseptic technique by his friend Joseph Lister and in 1878 he published a detailed series of 49 patients done “under the carbolic spray” with a mortality of 4%.16

These remarkable results inspired J Marion Sims to visit Keith. “I wished to see,” he wrote, “if there was anything peculiar to himself to account for his great success.” Sims published a detailed account of his observations17 which he considered so important that he published a fuller version as a monograph.1

Sims was particularly impressed with Keith’s attention to hemostasis, noting “he leaves no bleeding points, never closes the wound until he is sure that all bleeding has ceased; till he is sure that the peritoneum is perfectly dry.” He went on “Keith never hurries” yet “. . . I have never seen anyone cut down to the peritoneal cavity more quickly, though always carefully, remove a tumour with greater celerity, or close up the external wound so rapidly. . .”

Sims’ description of Keith the man offers further insights. “He has large, deep-blue eyes full of benevolence and gentleness . . . is as modest as a woman and of a character altogether lovely.” Part of the “secret” which Sims discovered was that “. . . his whole soul is wrapped up in his work, and after he has performed a difficult operation, he eats and sleeps but little till he knows that his patient is out of all danger.”

The American’s admiration for “this great and good man” is evident, and on return home, Sims adopted various aspects of the technique which he had seen in Edinburgh. As a result of this and other accolades Keith acquired an international reputation and patients were referred from all over Europe. He was asked to operate abroad, in Italy, in Boston, and in Mexico.4,5 Keith spent his last 7 years in London where he died in 1895.4,5

Conclusion

Thomas Keith’s photography shows scientific application, artistic creativity, and a deep understanding of the many subtleties of this new art form. John Hannavy, the photographic historian, describes his negatives as “a hugely important photographic treasure” and considers that his photography “combined technical excellence with pictorial mastery.”9 Keith’s contribution to photography was of such significance that it is remarkable that it did not appear in any of his obituaries. By contrast, his great contribution to improving the outcome for the new procedure of ovariotomy was recognized in Britain and around the world.

References

- Sims, JM. 1880. “Thomas Keith and ovariotomy.” American Journal of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children 13: 290-303.

- Wall, LL. 2006. “The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record,” Journal of Medical Ethics. 32(6): 346–350.

- Ritchie, LA. 2004. “Keith, Alexander (1792–1880).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Accessed 09 01, 2020. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/ 15262.

- Anonymous. 1895. “Obituary. Thomas Keith.” British Medical Journal 1003–1005.

- —. 1895. “Obituary. Thomas Keith.” The Scotsman, 10 October.

- Peddie, A. 1890. “Dr John Brown: His Life and Work; with Narrative Sketches of James Syme in the Old Minto House Hospital and Dispensary Days.” Edinburgh Medical Journal. 35: 1048–1062.

- Anonymous. 1910. “Obituary. George Skene Keith.” British Medical Journal 1: 237-238.

- Keith, Thomas. 1856. “The waxed paper process.” Photographic Notes 1: 101–104.

- Hannavy, J. 1981. Thomas Keith’s Scotland: The work of a Victorian amateur photographer 1852–57. Edinburgh: Canongate.

- McDowell, E. 1817. “Three cases of extirpation of diseased ovaria.” Eclectic Repertory and Analytical Review 7: 242–244.

- Wells, TS. 1862. “Table of cases of ovariotomy performed by Mr Spencer Wells.” Lancet 2: 687-689.

- Keith, Thomas. 1869. “Antiseptic surgery.” Lancet 94: 249-251.

- Keith, Thomas. 1863. “Cases of ovariotomy.” Edinburgh Medical Journal 8: 897-904.

- Keith, Thomas. 1872. “Third series of fifty cases of ovariotomy.” Lancet 100: 702-703.

- Keith, Thomas. 1876. “On the results of the cautery in the treatment of the pedicle in ovariotomy.” Lancet 107: 562.

- 1880. “Ovariotomy.” British Medical Journal 1: 931–932.

- Sims, J Marion. 1880. Thomas Keith and ovariotomy. New York: W. Wood & Co.

IAIN MACINTYRE, MD, FRCSEd, worked as a surgeon in Edinburgh. He has had a long association with the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and he was Vice President of the College during its 500th anniversary celebration. He was surgeon to the Queen in Scotland until he retired in 2004. Since retiring he has been involved in the history of medicine and his books include Surgeons Lives, an anthology of biographies of Fellows of the RCSEd and Scottish Medicine – an Illustrated History of which he was joint author. He is a past President of the British Society for the History of Medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021