JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

| Fig 1. A painting of Mary Wortley Montagu by Jonathan Richardson the Younger. Via Wikimedia. |

There are few examples of people with no medical training who independently make significant advances in medical practice. One such person was the elegant, aristocratic Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762)—daughter of Evelyn Pierrepont, first Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull—whose portrait is in the splendid Library Room at Sandon Hall, Staffordshire. It was painted in 1725 by Jonathan Richardson the Younger (Fig 1), but the artist has deceived the viewer by kindly concealing her unsightly facial scarring, the remnant of smallpox infection in 1715. Lady Mary was an unusually brilliant and audacious woman, who in childhood at Thoresby Hall in Nottinghamshire set herself to “stealing” her education, studying Latin when, she said, “everyone thought I was reading nothing but romances.”1

She became a widely respected, if eccentric, traveler and writer of letters, poetry, and prose. In 1712 she eloped with and married Edward Wortley Montagu of Wortley Hall in South Yorkshire. They moved to London in 1715 where she soon immersed herself in intellectual society and in the courts of both George I and the Prince of Wales. In the same year she survived an attack of smallpox.

Lady Mary accompanied her husband when he was appointed British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople in August 1716. They traveled through Europe during which she wrote long letters describing her travels. With her restless intelligence, she investigated Turkish and European cultures and customs, which she detailed in erudite, amusing letters and notes for a travel book. When her husband was recalled to London in 1718 she formed several influential friendships in regal and aristocratic circles. She also embarked on a personal quest to control or eradicate smallpox (variola).i

Smallpox

In Lady Mary Montagu’s time, smallpox had replaced plague as Europe’s most devastating disease. The first written description of smallpox2 was in Arabic by Rhazes in about AD 910; Thomas Sydenham3 lucidly described the British epidemic of 1667–69. But smallpox was mentioned in Egyptian writings as early as 3700 BC, and pox scars were found on the mummy of the pharaoh Rameses V.

In Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s time, the eighteenth century, smallpox had killed 400,000 Europeans each year with a mortality rate of 15 to 45 percent. But how was this pestilence to be prevented?

Giacomo (Jacobus) Pylarini had initiated variolation (the inoculation of material from human smallpox) in three children in Constantinople4; and Emanuel Timonius (1669–1718) of Constantinople (made FRS in 1703) commended this practice to the Royal Society in 1714 with his paper communicated by John Woodward MD, FRS.5

Lady Mary had a vested interest. She had not only lost her brother to smallpox but had nearly perished with it herself. In Turkey she discovered that inoculation (with live smallpox virus) was a common procedure in folk medicine, administered by old Greek women who made it their business. Charles Maitland was the Aberdeen-educated surgeon at the embassy. With him she investigated the Greek women’s practice (Fig 2):

The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless by the invention of ingrafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated.

. . . the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lye upon the head of her needle, and after that binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell.

— Letter from Lady Montagu to Mrs. S.C., Adrianople, April 1, 1717

|

| Fig 2. Letter from Lady Montagu to Mrs. S.C., Adrianople, April 1, 1717. |

While residing in Turkey, with Maitland’s help she bravely had her nearly five-year-old son inoculated.ii She was not the first Western European to have a child inoculated, but she was the first to bring the practice back to England.6

In Spring 1721, with an epidemic raging in England, she persuaded a reluctant Maitland to inoculate her daughter.7 The method consisted of “inoculating” pus from a person who suffered from smallpox into an arm vein of one who had not yet been attacked by the disease. This operation usually caused a mild illness, which then protected against further attacks.

She interested Caroline, Princess of Wales, in the procedure. Caroline had her own children inoculated successfully,8 and then arranged the famous experiment when Maitland inoculated six condemned prisoners in Newgate gaol, the so-called “Royal Experiment” conducted in the presence of the royal physicians Sir Hans Sloane and Dr. John George Steigertahl. In return, all six lives were spared from hanging. For this she was widely condemned in a vicious debate between those defending and those attacking the practice. Lady Mary contributed a text under the pseudonym “a Turkey Merchant.” In it, she not only defended inoculation but attacked the crude techniques sometimes performed in England, challenging the doctors of the day. Despite this, variolation was introduced to America in 1721 and Jan Ingen-Housz inoculated the Austrian Royal family, which included the child Marie Antoinette. The estimated mortality rate was 2 to 3%. In the winter of 1721–22, Thomas Nettleton, a Yorkshire physician aware of earlier accounts of variolation, inoculated over thirty people in Halifax, all of whom developed mild smallpox and survived.9

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu has been described as a literary bluestocking and leader of society in London. She had a brief affair with Alexander Pope that ended badly with scathing satires and acrimonious writings from them both. In later visits to Italy and France, she had affairs with Francesco Count Algarotti and with an Italian bandit Ugolino Palazzi. “Bluestocking” she was not.

She left England and her husband in 1739 to live abroad, returning to England shortly before her death from cancer. She died at Great George Street, Mayfair, on 21 August 1762, and was buried in Grosvenor Chapel in South Audley Street. Isaac Reed edited her poems posthumously in 1768. Her letters and travels were first published in 1785. James Dallaway published The Letters and other Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in 1803.

Jenner’s Vaccinationiii

|

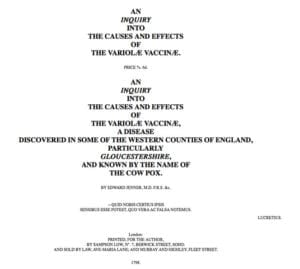

| Fig 3. Jenner’s Variolae Vaccinae, 1798. |

The subsequent history is too well known to justify detailed repetition. Edward Jenner (1749 -1823), prompted by the observation of John Fewster,10 a local surgeon, famously observed that milkmaids who had cowpox (vaccinia) were resistant to smallpox. In May 1796, a dairymaid named Sarah Nelmes consulted him about a rash on her hand. He diagnosed cowpox and decided to test whether cowpox inoculation gave protection from smallpox. On the 14th of May, Jenner made scratches on the arm of James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of his gardener. He rubbed in material from the cowpox lesions on Sarah’s hand. James became ill and recovered fully a week later. But would it protect him from smallpox? On 1 July 1796, he variolated the boy. To his great relief, James did not develop smallpox, on this or on a subsequent occasion when retested. The accuracy of this delightful account has been questioned9 although his biographer certainly verified the details.11

In 1798, Jenner published his experiments on smallpox, citing twenty-three personal cases in his famous book dedicated to the illustrious physician Caleb Hillier Parry of Bath.12 (Fig 3) In it he stated:

what renders the Cow-pox virus so extremely singular, is, that the person who has been thus affected is for ever after secure from the infection of the Small Pox; neither exposure to the variolous effluvia, nor the insertion of the matter into the skin, producing this distemper.

Despite many controversies, further experiments confirmed Jenner’s conclusions. Jennerian vaccination superseded variolation.13 In May 1980 the World Health Assembly announced that the world was free of smallpox. On the 200th anniversary of Jenner’s discovery, a British stamp was issued with a drawing of Blossom (Sarah Nelmes’s cow); within the cow’s markings Jenner is shown inoculating James Phipps.

The eminent broadcaster Andrew Marr in 2012, commented:

No human being who has ever lived has saved more lives in history than the simple country doctor from Gloucestershire.

End notes

- Latin variola, a pustule, pox (first used to describe smallpox in 1593)

- From Latin inoculare to engraft, from in- + oculus eye, bud

- First used in 1799, from Latin vaccīnus (< vacca cow),

References

- Grundy I. Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley. Oxford: OUP, 1956.

- Norman JM, editor. Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography. 5th ed. Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1991, 837, no. 5404. Translated by Channing into Latin and into English. See Medical Classics 1939;4:22-84.

- Sydenham T. Observationes medicae in circa morborum acutorum histioriam et curattionem. 4th ed. London: G. Kettilby, 1685. Cited in: Norman, Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography.

- Pylarini Giacomo. “Nova et tuta variolas excitandi per transplantationem methodus.” Phil Trans 1714-16;29:393-9.

- Timonius E. “An Account of the Procuring the Small Pox by Incision or Inoculation, as it has for some time been practiced at Constantinople Philos.” Trans 1714-16;29:72-82.

- Halsband R. “New light on Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s contribution to inoculation.” J Hist M Allied Sci. 1953;8(4):390-405.

- Arbuthnot J. Mr Maitland’s account of inoculating of the smallpox. London: J. Downing: 1722. Cited in: Norman, Garrison & Morton’s Medical Bibliography.

- Erikson A. “Smallpox inoculation: translation, transference and transformation.” Palgrave Commun 2020;6:52. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0431-6.

- Nettleton T. “A Letter from Dr. Nettleton Physician at Halifax in Yorkshire to Dr. Whitaker concerning the Inoculation of the Smallpox.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 1722;32(370):35. Cited in: Boylston A. “Smallpox inoculation: prelude to vaccination.” Hektoen Int Fall 2014.

- Dunea G. “Edward Jenner and the dairymaid.” Hektoen Int Spring 2018.

- Baron J. The Life of Edward Jenner MD. London: Henry Colburn, 1827.

- Jenner E. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae, a disease discovered in some western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire, and known by the name of Cow Pox. London: Sampson Low, 1798. Full text at: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29414/29414-h/29414-h.htm.

- Edwardes EJ. A concise history of small-pox and vaccination in Europe. London: HK Lewis, 1902.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 4 – Fall 2020

Summer 2020 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply