John Raffensperger

Fort Meyers, Florida, United States

Harald Hirschprung, a Danish pediatrician, in 1888 described the clinical course and pathology of two infants who died with congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis.1 Gastroenterostomy was adopted for the treatment of infants with pyloric stenosis, but surgical treatments were hampered by delayed diagnosis, malnutrition, and a lack of knowledge about electrolyte abnormalities. Chicago surgeons trained at Cook County Hospital and associated with area medical schools were among the first in the country to successfully operate on infants with pyloric stenosis.

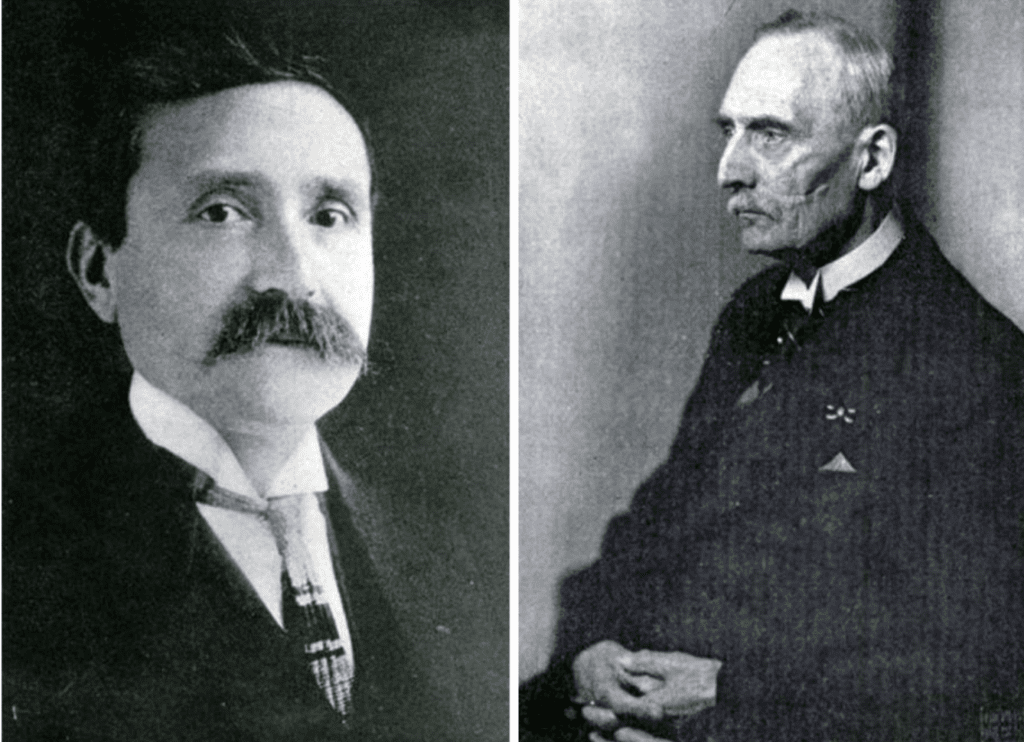

John B. Murphy, the “Stormy Petrel of Surgery,” graduated from Rush Medical School in 1889, was an intern at Cook County Hospital, then studied surgery with Theodore Billroth in Vienna.2 In 1904 Murphy performed a gastroenterostomy on a seven-week-old infant who was four pounds beneath his birth weight. The severely malnourished baby died twelve hours after surgery. George F. Thompson, who reported the case, described the bile-free vomiting, gastric distention, and palpable tumor characteristic of pyloric stenosis.3

Arthur Dean Bevan performed a gastroenterostomy on December 10, 1905, on an infant who thrived after surgery, and by the age of eleven months was taking whole milk, crackers, toast, and egg. This was the first survivor of the procedure in Chicago.4 Weller Van Hook, who had been an intern at Cook County Hospital and was the Chief of Surgery at Northwestern from 1899 to 1908, also operated on a baby who survived.5

By 1911 Bevan had operated on four infants, three of whom survived. He recommended gastric lavage before surgery and the administration of subcutaneous fluids.6 He said, “The children I have operated upon have developed in every way as healthy normal children. I pray you to give these poor little chaps the benefit of a good job of plumbing done early under the best aseptic and operative technique.” Arthur Dean Bevan graduated from Rush Medical College in 1883 and was chief of surgery at Presbyterian Hospital until 1934. He was a founding member of the American College of Surgeons, president of the American Medical Association in 1918, and president of the Chicago Surgical Society in 1908. In 1968 William Longmire addressed the American Surgical Society and counted Bevan as one of the “wise men in American Surgery.”7

In 1914 Harry. M. Richter reported on twenty-two operations for pyloric stenosis with only three deaths. This was the largest series in the United States with the lowest mortality rate.8 Richter, one of the most skillful and versatile surgeons of his day, had been a Cook County intern and was the surgeon-in-chief at Northwestern from 1929 to 1932. His son and grandson carried on the tradition of excellence in surgery.

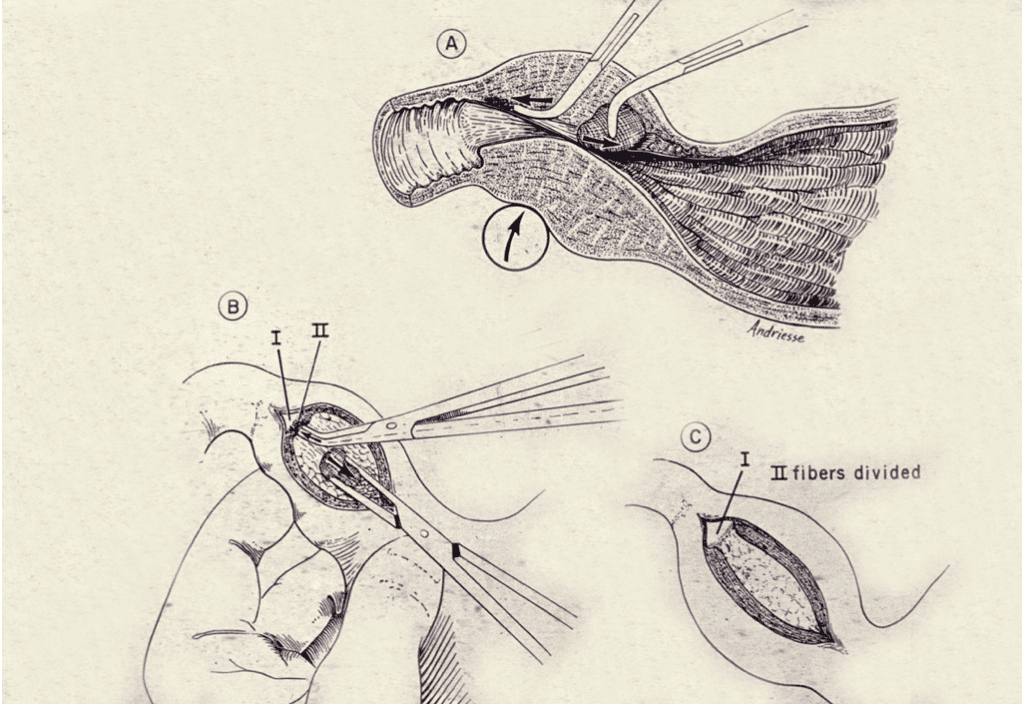

German was the language of science and medicine during the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Consequently, American surgeons overlooked the work of Pierre Fredet, a French surgeon. In 1907 Fredet separated the hypertrophied muscle down to the mucosa and then sutured the muscle transversely.9 In 1908 he reported on 135 infants treated with his method, stressed the need for operation before the onset of malnutrition, and described the metabolic alkalosis associated with the vomiting.10

Conrad Ramstedt of Munster, Germany, in 1911 modified Fredet’s operation by not suturing the muscle.11 The Ramstedt operation, because of its ease and simplicity, and a lower mortality than gastroenterostomy, became the treatment of choice for congenital pyloric stenosis. This operation is still used more than one hundred years later.

Dean Lewis, a Rush graduate in 1899 and a Cook County intern, said, “Gastro-enterostomy is well stood by infants if performed rapidly and without much trauma. Five infants have survived the operation and have developed normally.”12 Despite this success with gastroenterostomy, by 1917 Lewis had performed the Ramstedt pyloromyotomy on four infants with no deaths. These were the first reports of the Ramstedt operation in Chicago.13 Dean Lewis was a professor at Rush and chairman of surgery at the University of Illinois until he was called to Johns Hopkins to follow Halstead as professor of surgery.

In 1930 Bevan, demonstrating a Ramstedt operation to a “wet clinic,” said, “We have developed a technique which makes the Ramstedt operation one of the most finished pieces in the entire field of abdominal surgery.” During that clinic, he also did two cholecystectomies, drained an abdominal abscess, repaired bilateral undescended testicles, and performed a radical mastectomy for cancer.14

Edwin Miller, a graduate of Rush and the Cook County Hospital internship, joined the Rush faculty in 1915 and then served in France during World War I. He and Sumner Koch were attending surgeons at Cook County Children’s Hospital from 1920 until 1947. During that time, he published many papers on children’s surgery. Miller served in New Guinea during the Second World War and was surgeon-in-chief at Presbyterian Hospital from 1949 until 1954. In 1933, during a symposium called “Important Operations in Children,” Miller discussed errors in diagnosis of pyloric stenosis, perforation of the duodenal mucosa, incomplete separation of muscle fibers, bleeding, and evisceration. He suggested using a magnifying glass to ensure complete separation of the muscle and a transverse incision through the posterior sheath of the rectus muscle to prevent evisceration.15 In a 1964 report to the Chicago Surgical Society, he summarized the post-operative course of his patients who had a gastroenterostomy during infancy; all four had episodic gastrointestinal bleeding and two had definite marginal ulcers.16

Surgeons were concerned about leaving the gastric mucosa uncovered by muscle. Alfred Strauss, a Rush graduate in 1908, and Isaac Abt at Michael Reese Hospital studied a model of pyloric stenosis in dogs and modified the Ramstedt operation by cutting thin flaps of muscle that were sutured back around the mucosa.17 By 1918 Strauss had sixty-five surgical cases with three deaths.l8 By 1926 Abt and Stauss had reported on 221 patients with seven deaths—a 3% mortality rate.19 They recommended bismuth x-rays to make the diagnosis, infusions of subcutaneous saline, and blood transfusions. The operation lasted only twelve to fifteen minutes and feedings were commenced one hour after surgery. Of the seven infants who died, two were moribund upon admission to the hospital, one had peritonitis, two died with influenza during the epidemic of 1918, one had a pulmonary embolus, and one had multiple intestinal atresias. Max Thorek, who had been an intern at Cook County and founded the American Hospital and the International College, further modified the Ramstedt pyloromyotomy.20

Many physicians thought pyloric obstruction was caused by spasm rather than hypertrophy and avoided surgery. John Gerstley of Michael Reese treated spasm of the pylorus with paregoric, bromides, and thickened feedings given every two hours. He said, “Take the child away from the hands of nervous mothers and give the infant to calm unemotional nurses.”21 Perhaps his patients had milk intolerance or nervous mothers rather than hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Many infants who came to surgery were in fact malnourished as a result of delay in diagnosis. Isaac Abt, a Cook County Hospital intern and first director of the Sarah Morris-Michael Reese Children’s Hospital, educated physicians about early diagnosis and the need for surgery.22

Harry Oberhelman, while an attending surgeon at Cook County and chairman of surgery at Loyola, reported on eighty-five infants treated from 1925 until 1946.23 In three cases the diagnosis was wrong, two required re-operation, and there were four duodenal perforations. There were nine deaths, a mortality rate of 10.7%. Five deaths were due to “shock,” two resulted from evisceration, and one operation was incomplete. Another baby died with “cerebromalacia.” Dr. Oberhelman reported that during the last six years covered by his report, there had been only one death in fifty-one cases. John Keeley, Oberhelman’s associate and later an attending surgeon at Cook County and chairman of Loyola’s surgical department, was responsible for this improved survival. In 1949 Keeley discussed the need for pre-operative treatment of dehydration and nutritional deficiencies. He also recommended a high transverse incision, which essentially eliminated the postoperative evisceration seen so commonly in malnourished babies.24

Willis J. Potts, another graduate of Rush Medical School, became an associate professor at Rush and was on the staff at Children’s Memorial Hospital. In 1938 he reported to the Mississippi Valley Medical Society on operations for pyloric stenosis performed at Children’s Memorial Hospital.25 Ten of seventy-eight patients died between 1923 and 1932, a mortality rate of 12.8%. Between 1932 and 1937 the mortality rate was reduced to 3.55%. Potts emphasized palpation of the abdomen for the pyloric tumor with the stomach empty, while the baby relaxed with a sugar nipple. He also advised giving these infants 200 mL of dextrose in saline subcutaneously and recommended blood transfusions for especially sick babies. He avoided barium x-rays and emphasized emptying the stomach before an operation under ether anesthesia. Potts served in the Pacific during World War II and returned to Chicago to become the first full-time pediatric surgeon in Chicago. He is best known for his work with “blue babies.” In 1959 Potts reported on 760 operations between 1938 and 1959 with only one death, which occurred in a three-and-a-half-pound premature infant that he had personally operated upon.26

Earlier diagnoses and improved intravenous nutritional therapy markedly improved the pre-operative condition of these infants during the 1960s. The high transverse incision eliminated evisceration as a postoperative complication; routine emptying of the stomach and improved anesthetic techniques eliminated pulmonary complications. The mortality rate for infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis declined to near zero but misdiagnosis with severe malnutrition continued to be a problem.

Experienced clinicians are unduly proud of their ability to make the diagnosis by observation of peristaltic waves and palpation of the pyloric tumor. There are times when the baby simply will not relax and palpation is difficult. Gastrointestinal x-rays are not always reliable and there is reluctance to do barium studies for fear of aspiration. By the mid-1970s, real-time ultrasonography offered a safe technique to literally “see” inside the abdomen.27 Arnold Shkolnik interned at the Cook County Hospital in 1959 and completed residencies in pediatrics and radiology. He spent his entire professional career as a radiologist at Children’s Memorial Hospital. Shkolnik with ultrasonography demonstrated the hypertrophied muscle as a thick, hypoechogenic ring around a central “donut hole” in babies with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. This non-invasive technique solved the problem of delayed diagnosis.28

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, with greater ease in making the diagnosis and the virtual elimination of death and surgical complications, attention turned to eliminating pain, cosmetic improvement of the incision, reducing costs, and shortening the hospital stay. Minimally invasive surgery in the form of laparoscopy has replaced open methods for the Ramstedt operation.29

References

- H. Hirschprung, Falle von Angeboreber Pylorustenose,Beobachter bei Sauglingen, Jahrb.D.Kindeh, 27 [1885]:61-68

- Davis, L. J.B. Murphy, Stormy Petrel of Surgery, G.P. Putnam and Sons, 1938, New York, N.Y.

- Thompson, George F. Congenital Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis in Infants with report of an operated case. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, Vol. 3, October, 1906, pp521-530

- Cheney, H.W. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, Operation Followed by Recovery: Archives of Pediatrics, Feb. 1907, Vol. 24, pgs. 146-153

- Arey, Leslie B. Northwestern Medical School, 1859-1978, pg. 557, Northwestern Medical School, 1979, Chicago, Ill.

- Bevan, A.D. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, American Journal Diseases of Children Vol. 1, #2 Feb. 1911 pp. 85-95

- Ravitch, Mark, A Century of Surgery; Vol. l 1880-1980 Lippincott and Co. Philadelphia, 1981, pg. 1257

- Richter, H.M. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, A Study of Twenty-two Cases with Operation by the Author. Journal of the American Medical Association Vol. LXII Jan. 31, 1914, pgs. 353-356

- DuFour, H. and Fredet, P. La Stenose Hypertrophique Du Pylore Chez le Nourrison Et Son Traitment Chirurgical, Bulletin et Memoires. Societe de Medecine De Paris. 1907 24, 1221 208-217

- DuFour, H. Fredet, P. La Stenose Hypertrophique Du Pylore Chez Le Nourrison et Son Traitement Chirugical Revue de. Chirugie, 1908, 37 208-253

- Ramstedt, C., Zur Operation der Angeboren Pylorostenose, Medizin Klinische 8, [1912]: 1702

- Lewis, D. Grulee C. The Pylorus After Gastroenterotsomy for Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, Journal of the American Medical Association, 64, Jan. 30, 1915 pp 410-412

- Dean Lewis, Clinic at Presbyterian Hospital, Chicago International Clinics, Vo1.11 1918 pp79

- Bevan, A.D. Clinic of Arthur Dean Bevan, Presbyterian Hospital, Chicago Surgical Clinics of North America Vol. 10, #2 April 1930 pgs. 185-189

- Miller, E. Complications of Pyloric Stenosis, in Symposium on Important Operations in Children, Chicago. Surgical Clinics of North America, Vol 13, #5, 1933, Chicago. pp. 1111-1115

- Miller, E. Hill, B.J. Long Range Follow up of Infants Upon Whom a Gastroenterostomy had Been performed during the First Weeks of Life. Proceedings of the Institute of Medicine, #24-25 1962-65, pg. 137

- Strauss, A.A. A New Method of Pyloroplasty For Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. LXV #18 Oct 30, 1915 1533-1537

- Strauss, A.A. Clinical Observations on Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, Report of 101 Cases. Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 71 #10 Sept. 7, 1918, pp 807-810

- Abt, LA. Strauss, A.A. Clinical Study of 221 Operated Cases of Hypertrophic Congenital Pyloric Stenosis: Medical Clinics Of North America, Vol. 9, March 26, 1926, pp 1305-1315

- Thorek, M. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis with Special Reference to Surgical Treatment. Illinois Medical Journal Vol. 44 Nov. 1923, 334-338

- Gerstley, J. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis Re-feeding a Method of Treatment and Possible Prophylaxis Illinois Medical Journal, #47, May 1925, pp 371-374

- Abt. LA. Baby Doctor, McGraw-Hill Book Co. Inc. and Whittlesey House, Londonn-New York, 1944 pages 134-154

- Oberhelman, H.A. Eighty-Five Infants with Pyloric Stenosis Treated at the Cook County Hospital Read at the Chicago Surgical Society, March 3, 1946. Proc. Institute of Medicine, Chicago, #16, 1946, pg 234

- Keeley, J.L. Transvers Incision for Pyloroplasty; Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics 89, Dec. 1949, pp 748-751

- Potts, W.J. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis Presented at the 4th annual meeting of the Mississippi Valley Medical Society, Hannibal Mo. Sept. 28, 1938, Mississippi Valley Medical Journal Vol. 61 May 1939 84-87

- Potts, W.J. The Surgeon and the Child, W.B. Saunders Co. 1959, pp. 153-157

- Teele, R.I. Smith, E.H. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of Idiopathic Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis New England Journal of Medicine 296; 1149-1150 1977

- Shkolnik, A. Applications of Ultrasound to the Neonatal Abdomen; Radiologic Clinics of North America Vol. 23 #1 March 1985, pp141-156

- Hall NJ, Pacilli M, Eaton S, et al. Recovery after open versus laparoscopic pyloromyotomy for pyloric stenosis: a double-blind multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Vol. 373, 2009, pp390-398

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, graduated from the University of Illinois in 1953, interned at the Cook County Hospital, served in the U.S. Navy and returned to Cook County for training in surgery. He was on the attending staff at Cook County until 1970 when he went to the Children’s Memorial Hospital. He is the author of surgical texts, novels, and works of medical history, including The Old Lady on Harrison Street: History of the Cook County Hospital, 1883-1995.

Acknowledgments

Heather J. Stecklein, Librarian and Archivist at the Rush University Medical Center for biographic material on Drs. Arthur Dean Bevan, Dean Lewis, and Edwin Miller. Richard Sims, Special Collections Librarian, and an expert at finding references, found many of the original papers in the Galter Library of Northwestern University.

Leave a Reply