Jayant Radhakrishnan

Nathaniel Koo

Darien, Illinois, United States

Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the world. One would expect consensus regarding its management, but that has not been the case from the time the appendix was first identified.

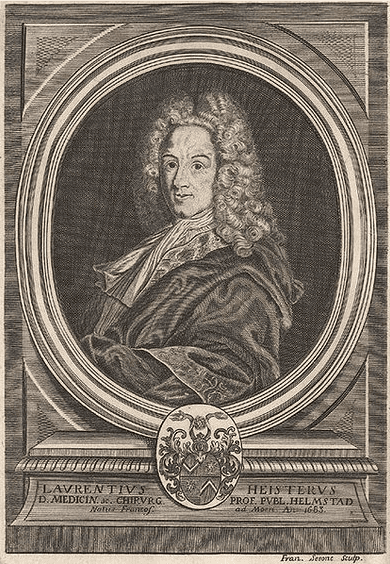

Galen (129–216 CE) was not permitted to dissect human bodies, so he dissected monkeys. Since monkeys do not have an appendix, he was unaware that such an organ existed. Because of Galen’s huge influence on European and Arabic medicine for centuries, other physicians also never recognized it. It is unclear whether Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) first depicted the appendix in an anatomical drawing in 1492 or Giacomo Berengario da Carpi (1460–1530) first described it in 1521. In 1711, Lorenz Heister (1683–1758) wrote about an infected appendix as follows: “I found the vermiform process of the caecum preternaturally black, adhering closer to the peritonӕum than usual.” He deduced that “this instance may stand as a proof of the possibility of inflammations arising and abscesses forming in the appendicula” and advised that “when, in practice, we meet with a burning and pain where this part is situated, we ought to give attention to it.”1 He was ignored.

In 1886, pathologist Reginald Heber Fitz (1843–1913) presented a series of 257 cases and named the inflammation “acute appendicitis.”2 Four years later in a follow-up paper, he reported on seventy-two operated cases of appendicitis, of whom fifty-three survived. He urged early diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment.3 He was heeded.

Before the advent of antibiotics, excision of the infected appendix and drainage of pus was the only treatment possible. Apart from Charles McBurney (1845–1913) in New York, four other surgeons made invaluable contributions in this early period: John B. Murphy and Albert Ochsner in Chicago and John Sherren and Frederick Treves in London.

John Benjamin Murphy (1857–1916) was the most famous surgeon in Chicago at the time. He had been a professor at the College of Physicians and Surgeons (now University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago), at Rush University, and finally at Northwestern University. He was on the staff of many hospitals but he favored Mercy Hospital. William J. Mayo considered him “the surgical genius of our generation.” Nevertheless, many surgeons were bothered by his self-aggrandizement. One such incident is purported to have occurred after President Theodore Roosevelt was shot in Milwaukee by John Schrank on October 14, 1912. The President was transferred by train from Milwaukee to Chicago for treatment. While a host of prominent doctors awaited his arrival at the main railway station in Chicago, Murphy supposedly took an ambulance to the previous station and spirited the injured President away to Mercy Hospital for treatment. Loyal Davis considered him a harbinger of trouble and entitled the biography he wrote JB Murphy, the stormy petrel of surgery.4

On March 2, 1889, after reading two papers on perityphlitis, Murphy convinced a young man at the Cook County Hospital to have an immediate appendectomy although he only had symptoms for eight hours. The patient recovered promptly and uneventfully following removal of his inflamed, non-perforated appendix. True to form, Murphy declared that this was the first case operated upon in the United States, as it preceded McBurney’s operation by twenty days. Based on this one case, he advocated vociferously for early surgery and condemned expectant medical treatment.5 His presentation did not go over well, but being supremely confident in himself, he continued to operate emergently. Within five years he presented a detailed report on 2,000 appendectomies. His mortality rate dropped from 11% in the first 100 cases to 2% in the last 100. During this presentation he again castigated those who wished to wait and watch. He believed that all cases of appendicitis must be operated upon immediately regardless of whether the peritonitis was localized or generalized. In his view, the increased number of deaths reported in patients with generalized peritonitis was because of “excessive manipulation, sponging, flushing, adhesion separating, and prolonged operation.” Postoperatively his patients were kept in the Fowler’s (semi-sitting) position, oral intake was discontinued, and a large amount of water was administered by a slow rectal drip. He supplemented this drip with strychnine for reasons he did not explain, and he induced bowel emptying with small doses of calomel (mercury chloride) beginning eight hours after the operation.6 Murphy was considered a master diagnostician and he demonstrated that skill unto the very end when he correctly prophesied about himself, two days before his death, “I think the necropsy will show plaques in my aorta.”4

Albert John Ochsner (1858–1925) was Murphy’s contemporary but also his antithesis, with no illusions of grandeur. In the preface to the first edition of his popular clinical surgery book (five editions of which were published), he stated “the author lays no claim to the invention of a single new operation, nor has he produced a new or modified instrument…”7 He was Professor and Chair of Clinical Surgery at the University of Illinois with a private practice at Augustana and St. Mary’s Hospitals. In his chairman’s address at the 52nd annual meeting of the American Medical Association, he described his approach to the management of acute appendicitis in 565 patients he treated between January 1, 1898 and May 1, 1901. They were classified into three groups. The first group presented with diffuse peritonitis. Ten of these eighteen patients (55.5%) died. Those in the second group had a gangrenous or perforated appendix on admission. Of 179 patients in this group that he operated upon, nine (5%) died. Those in the third group had recurrent appendicitis and were operated on in the interval between attacks or early in the onset of an attack. Only one out of 368 in this group died. In all, twenty patients died, an incidence of 3.5%. He concluded that intestinal peristalsis spread a localized infection into the generalized peritoneal cavity and that the spread of infection could be contained by discontinuing all oral intake, evacuating the stomach completely by lavage, not using cathartics to empty the bowels, and administering a salt solution by rectal infusion but not a large enema. He also placed patients in Fowler’s position to allow pus to gravitate into the pelvis. He believed that such management converted the most dangerous appendicitis with generalized peritonitis into a mild and harmless disease. He favored surgery after the control of peritonitis in the high-risk group. He also warned practitioners that this form of management did not work as well in the very young and the very old.8

His book on appendicitis was lauded and two editions were published. Clearly, he was an accomplished surgeon who made major contributions to surgery, but he is better known for mentoring his cousin’s son, Alton Ochsner, the founder of the Ochsner Clinic in New Orleans, Louisiana. When Alton started his internship at Augustana Hospital in Chicago, he found it difficult to keep pace with his hard-charging uncle and complained to his family that “he is going to kill me before we get through.” Once, when asked to come early the next morning for medical discussions, Alton complained that he would be too tired that early in the day. The elder surgeon replied, “You are an Ochsner and you can take it.”9

In England, a contemporary of the two Chicago surgeons was the equally accomplished James Sherren (1872–1945). He went to sea at thirteen years of age, rapidly became a proficient sailor, and was a master mariner by the age of twenty-one. At twenty-four, he gave up the sea and enrolled at the London Hospital Medical College. After graduating, he joined the staff of London Hospital. He was initially interested in neurosurgery and started working with the eminent neurologist Henry Head. To understand the sensations experienced when injured nerves regenerate, Head had Sherren and the psychologist WHR Rivers divide all cutaneous branches of his left radial nerve at the elbow while preserving the motor branches. As control for the experiment, they chose not to use the neurologically intact contralateral forearm. They chose instead the glans penis because it “faithfully registers all the features of protopathic and deep sensation experienced in his denervated left forearm and hand…” Consequently, Rivers dutifully retracted Head’s foreskin and dipped the tip of his penis in hot or cold water and recorded the sensations for four years!10

In time, Sherren became interested in the new specialty of abdominal surgery and particularly in the diagnosis and management of appendicitis. His continued interest in the manifestation of cutaneous tenderness in visceral diseases lead to his identification of hyperesthesia in the area between the summit of the right iliac crest, the umbilicus, and the pubic symphysis, now named Sherren’s triangle. He stated that hyperesthesia here was diagnostic of obstructive appendicitis and immediate surgery was indicated.11

After reading Ochsner’s A Handbook of Appendicitis, Sherren agreed with that line of management for appendicitis. In June 1905, he wrote in the Practitioner, “If we are able to see a case within the first 24 to 36 hours when the disease is probably limited to the appendix, operation should be performed and the appendix removed. After this most favourable time has passed I am strongly of the opinion that if possible we should wait until the attack is over and remove the appendix in a quiescent period in three months’ time.”11 He and his trainees standardized Ochsner’s basic concept into the Ochsner-Sherren regimen. Hamilton Bailey, who trained with Sherren, described the regimen in detail and reported on 315 of his own patients treated between August 1927 and November 1929. Four of 242 patients that Bailey operated upon within six hours of admission died, while only one of seventy-three treated by the Ochsner-Sherren method died. Bailey emphasized that the regimen was not a substitute for surgery but preparation for it. Bailey administered one dose of intravenous mercurochrome at the completion of the operation in all patients with a gangrenous appendix. It is unclear why and whether he learned this from Sherren or if it was his own idea.12

In 1926, at the peak of his career and fame, Sherren suddenly left surgery and returned to the sea. Sir Henry Souttar described Sherren’s last day as follows: “One afternoon when he had finished his operating list, he took off his gloves and said to his senior theatre technician, Macgowan: ‘Well, goodbye, that was my last operation.’ He shook hands with everyone in the theatre and then, having changed in the surgeon’s room, he went down in the lift alone. In the front hall waiting for him was Sir Ernest Morris, the House Governor, the only man that knew he had resigned, holding his hat and coat. The hall porter came forward to turn off his light on the board, but Sherren waved him away, stood for a moment looking at his name, and then himself turned off the switch. He shook hands with Ernest Morris, and then left the scene of his surgical triumphs forever.”11

Sir Frederick Treves (1853–1923) was a contemporary of Sherren’s at London Hospital but senior to him. He was also a master mariner and renowned for his treatment of appendicitis. Treves used terms such as typhlitis, paratyphlitis, and perityphlitis but he understood that the problem arose in the appendix. He favored surgery on the fifth day when peritonitis was localized and in recurrent cases, he believed the appendix should be removed between attacks. Treves revealed that his suggestion about removing the appendix between attacks was not well received. He became even more famous in 1902 when King Edward VII developed appendicitis before his scheduled coronation on June 26th. The doctors in attendance unanimously agreed that the King must be operated upon immediately but the King refused, believing it was his duty to go through with the planned coronation at Westminster Abbey. The King kept repeating before Treves, “I must keep faith with my people and go to the Abbey for the coronation” until Treves, in exasperation, finally said, “Then, Sire if you go to the Abbey you will go as a corpse.”13 This stark statement got through to the monarch. On a hastily set up table in the music room of Buckingham Palace, Treves drained the abscess through a generous incision on the rather corpulent belly. He washed out the cavity and left two rubber tubes to drain it, but he did not try to remove the appendix. The monarch was up and smoking a cigar in bed the next morning. Although the King’s appendix was still in situ, “appendicectomies” became common in Britain after that.

Unfortunately, in 1900 Treves missed the diagnosis of perforated appendicitis in his eighteen-year-old youngest daughter, Hetty, and she died. He himself died of peritonitis in 1923, supposedly from cholecystitis. No autopsy was carried out so one can only speculate about the source of the peritonitis.

From these beginnings, urgent excision of the acutely inflamed appendix through an abdominal incision became the standard of care until the 1980s. In 1980 Kurt Semm, a gynecologist, introduced general surgeons to laparoscopic appendectomy.14 After initial skepticism, the technique had a meteoric rise in popularity to supplant the open operation entirely. Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) came into the picture in 2004.15 NOTES appendectomies have been carried out via esophago-gastroscopy,16 through the vagina,17 and by the transcolonic route,18 but the technique has not gained general acceptance.

In the twentieth century, along with surgical innovations, steps were taken to improve diagnostic accuracy of appendicitis by using clinical scoring schemes, specific laboratory tests, and imaging modalities, individually and in combination. The objective was to diagnose the condition early to avoid perforated or gangrenous appendicitis while simultaneously eliminating misdiagnoses and the removal of normal appendices.

Once antibiotics became available, starting with sulfa drugs in 1935, they were used as adjuncts to surgery, especially for complicated appendicitis. From the 1940s, they have also been used to keep the infection in check if surgery was not immediately possible. This approach was particularly useful on submarines in World War II and when US ships were in enemy waters during the Cold War.19

The question being studied now is whether antibiotics can cure appendicitis. To answer this question, one must know how often antibiotic treatment of appendicitis fails and under what circumstances, the recurrence rate after successful antibiotic treatment of acute appendicitis, and how often an antibiotic-treated patient eventually requires surgery. It is also worth knowing whether antibiotic treatment or surgery has fewer complications and which modality is less expensive. Many short-term studies in adults and children have demonstrated successful non-operative treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis with antibiotics.20 Of importance are three sequential reports of 530 adult patients at one, five, and seven years after treatment. At one year, the primary end point for the surgical group was a successfully completed appendectomy while in the antibiotic treated group, it was discharge from the hospital without requiring an appendectomy and no recurrence within a year. The success rate of the surgical group was 99.6%. Among the antibiotic treated group, 72.7% did not require surgery within a year. Of patients who required delayed surgery, only 10% had complicated acute appendicitis and there were no major complications or intraabdominal abscesses in the entire group.21 Within five years, 39.1% of antibiotic-treated patients required appendectomy; this number includes the fifteen who required surgery during the initial hospitalization. Complications were 17.9% higher in the surgery group. While the length of hospitalization was the same in both groups, the surgery group took eleven more sick days.22 Secondary evaluations of this cohort demonstrated that quality of life and patient satisfaction were similar between the appendectomy group and those in whom antibiotic treatment was successful. However, patients who required an appendectomy because antibiotic treatment failed were less satisfied.23 The overall cost of appendectomy was 1.4 times greater than that of the antibiotic-treated group; however, only open appendectomies were done in the study. The length of hospitalization, complications, number of sick days taken by the patient, and cost would be different for laparoscopic appendectomy.

Now that studies have demonstrated that uncomplicated acute appendicitis can be treated safely with antibiotics, studies such as the Appendicitis Acuta (APPAC) II must not only follow the initial patients over the long term to confirm that antibiotic treatment truly helps avoid surgery, but they also have to study details of antibiotic regimens. It has yet to be determined which antibiotics, singly or in combination, have the best results with the least side effects and complications, are the simplest to administer (orally vs parenterally and inpatient vs outpatient), are the most economical to use, and whether this form of treatment can be used safely in countries with wide-ranging medical facilities and in different groups of people.

Acute appendicitis is most common in children and adolescents, hence the feasibility of non-operative management in these age groups is also being investigated. Earlier studies in children gave some conflicting information. A recent study with a five-year follow-up has demonstrated that non-operative care can be safely delivered in children.24

An unexpected effect of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a significant decrease in patients presenting with acute uncomplicated appendicitis. Respiratory infections do not seem to cause appendicitis, however, the annual incidence rates of acute uncomplicated appendicitis and influenza cointegrate. Similar environmental factors, etiologic determinates, or pathogenic mechanisms may affect both their incidences.25 Thus, the decreased incidence of acute appendicitis may owe to the same factors that reduced upper respiratory infections and influenza during the pandemic, i.e., people isolated themselves, maintained social distancing, and wore masks.26 It may also be that patients were treated by telemedicine and at urgent care centers, or that acute appendicitis was being overdiagnosed and overtreated previously and some of these patients would have resolved spontaneously without medical management. On the other hand, it could also be that patients with acute appendicitis were diagnosed with COVID-19-associated gastrointestinal symptoms and some died.27 Contrary to previous beliefs, perforated appendicitis appears to be a different disease not related to diagnostic or therapeutic delay.25

At the start of the twentieth century, the foremost surgeons were trying to decide whether to operate or not for acute appendicitis. In this century, patients will have to decide for themselves whether to have the appendix removed in the first instance and be done with it, or to trust the statistics that they have a greater than 60% chance of never requiring an operation for acute appendicitis. Of course, the unoperated patient would have no way of knowing if an early cancer or a chronic infection is being missed.24 In addition, if they opt for the non-operative approach, every time they have a bellyache they will wonder whether they should make a trip to the emergency room to be checked out and to receive antibiotics.

Patients may even have to decide whether to have a prophylactic appendectomy if studies conclusively demonstrate a genetic predilection to developing acute appendicitis.28 Conversely, patients may have to try and hang on to their appendices if other studies confirm that there is a higher incidence of inflammatory bowel disease, Clostridium difficile infections, and colorectal cancer after appendectomy.29

Heister described appendicitis over 300 years ago and the debate regarding its treatment that started then is still ongoing.

As Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr (1808–1890) said in 1849: “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose” (the more things change, the more they stay the same).

Bibliography

- Heister L (1711): Medical chirurgical and anatomical cases and observations (translated by Wirgman G, London printed by J Reeves 1755) in Major R H (ed). Classic descriptions of disease, with biographical sketches of the authors. Springfield, Illinois & Baltimore, Maryland: Charles C Thomas, 1932. pp. 615-617.

- Fitz RH (1886): Perforating inflammation of the vermiform appendix; with special reference to its early diagnosis and treatment. Reprinted from the Trans Assoc Amer Physicians June 18, 1886. Philadelphia Wm J Dornan printer 1886. Permanent Link: http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/65711100R.

- Fitz RH (1890): Appendicitis: Some of the results of the analysis of 72 cases seen in the past four years. Boston Med Surg J 122:619-620. doi: 10.1056/NEJM189006191222508.

- Rutkow IM (1987): A history of The Surgical Clinics of North America. Surg Clin North Am. 67(6):1217-1239.

- Meyer KA, Hyman S (1959): John B Murphy. An inquiry into his life and scientific achievements. John B Murphy Memorial lecture. On the occasion of the 24th Annual Congress of the International College of Surgeons. In honor of the Chicago Medical Society and three great Chicago Surgical Pioneers. Grand Ballroom Palmer House, Chicago, September 16, 1959.

- Murphy JB (1904): “Two thousand operations for appendicitis” with deductions from his personal experience. Amer J Med Sci 128(2):187-211.

- Ochsner AJ, Percy NM (1911): A new clinical surgery. Chicago: Cleveland Press. Third Edition. pp. 8-9.

- Ochsner AJ (1901): The cause of diffuse peritonitis complicating appendicitis and its prevention. JAMA 36(25):1747-1754. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470250001001.

- Ventura HO (2001): Albert Ochsner, MD: Chicago surgeon and mentor to Alton Ochsner. The Ochsner Journal 3(4);223-225.

- Rivers W.H.R, Head H (1908).”A human experiment in nerve division”. Brain.31(3): 323-450 reprinted by Compston A (2009): From the archives Brain132(11):2903-2905 doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp288

- Moore AMA (1973): James Sherren-Surgeon and sailor. Brit J Surg 60(11):841-846.

- Bailey H (1930): Ochsner-Sherren (delayed) treatment of acute appendicitis: Indications and technique. Brit Med J 1(3603):140-143.

- Ellis H (2015): The first Royal appendix abscess drainage. J Perioper Pract 25(5):115-116 doi:10.1177/175045891502500505.

- Litynski GS (1998): Kurt Semm and the fight against skepticism: Endoscopic hemostasis, laparoscopic appendectomy, and Semm’s impact on the “Laparoscopic revolution”. J Soc Laparoscopic & Robotic Surgeons 2(3):309-313.

- Kalloo AN, Singh VK, Jagannath JB, et al (2004): Flexible transgastric peritoneoscopy: a novel approach to diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in the peritoneal cavity. Gastrointest Endosc 60(1):114-117. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01309-4.

- Rao GV, Reddy DN, Banerjee R (2008): NOTES: Human experience. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin North Am 18:361-370.

- Yagci MA, Kayaalp C (2014): Transvaginal appendectomy: A systematic review. Minim Invasive Surg. Dec 29. doi:10.1155/2014/384706 Corrigendum to Transvaginal appendectomy: A systematic review. Minim Invasive Surg 2015 Jun 28. doi:10.1155/2015/527140.

- Chen T, Xu A, Lian J, et al (2021): Transcolonic endoscopic appendectomy: A novel natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) technique for the sessile serrated lesions involving the appendiceal orifice. Gut 0:1-3 doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323018.

- Radhakrishnan J, Koo N (2021): Atypical appendectomies. Hektoen International Sections/Surgery/Summer 2021. https://hekint.org/2021/07/13/atypical-appendectomies/& https://www.instagram.com/p/CVDXKi7Lnzb/.

- Moris D, Paulson EK, Pappas TN (2021): Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis in adults. A review. JAMA 326(22):2299-2311. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.20502 Comment & response: Talan DA & Huerta S & reply by Moris D, Paulson EK, Pappas TN (2022): JAMA 327(12):1183-1184.

- Salminen P, Paajanen H, Rautio T, et al (2015): Antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for treatment of uncomplicated acute appendicitis. The APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA 313(23): 2340-2348. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.6154.

- Salminen P, Tuominen R, Paajanen H, et al (2018): Five-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy for acute appendicitis in the APPAC randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320(12):1259-1265 doi:10.1001/jama.2018.13201.

- Sippola S, Haijanen J, Viinikainen L, et al (2020): Quality of life and patient satisfaction at 7-year follow-up of antibiotic therapy vs appendectomy for uncomplicated acute appendicitis. A secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg 155(4):283-289 doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2019.6028.

- Patkova B, Svenningsson A, Almström M, et al (2020): Nonoperative treatment versus appendectomy for acute nonperforated appendicitis in children. Five-year follow up of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Ann Surg 271(6):1030-1035.

- Alder AC, Fomby TB, Woodward WA, et al (2010): Association of viral infection and appendicitis. Arch Surg 145(1):63-71.

- Rodgers L, Sheppard M, Smith A, et al (2021): Changes in seasonal respiratory illnesses in the United States during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Clin Infectious Dis 73(S1):S110-117.

- Rosenthal MG, Fakhry SM, Morse JL, et al (2021): Where did all the appendicitis go? Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on volume, management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in a nationwide, multicenter analysis. Ann Surg open 2(1):e048. doi: 10.1097/AS9.0000000000000048.

- Gaitanidis A, Kaafarani HMA, Christensen MA, et al (2021): Association between NEDD4L variation and the genetic risk of acute appendicitis. A multi-institutional genome-wide association study. JAMA 156(10):917-923 doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2021.3303.

- Lee S, Jang EJ, Jo J, et al (2021): Long-term impacts of appendectomy associated with increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease, infection, and colorectal cancer. Internat J Colorectal Dis 36(8): 1643-1652 doi: 10.1007/s00384-021-03886-x.

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP, completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending pediatric surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago from where he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.

NATHANIEL C. KOO, FAAP, is an Assistant Professor of Surgery at the Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. He obtained his medical degree and general surgery training at the University of Illinois, College of Medicine, Chicago. Then after two years of research at Northwestern University he completed a Pediatric Surgery Fellowship at Lurie Children’s Hospital, Chicago. He is an attending Pediatric Surgeon at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022 and Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply