Arpan K. Banerjee

Solihull, United Kingdom

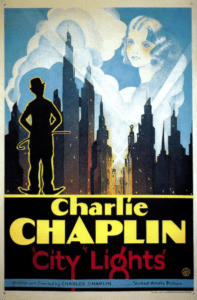

Fig 1. Poster for Chaplin film City Lights. 1931. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

For doctors and lovers of cinema, 1895 was an important year. On November 8, 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen, a fifty-year-old professor of physics, discovered X-rays in his laboratory in Wurzburg, Germany. On March 22 1895, the Lumiere brothers presented the first film on a screen to an audience of 200 in Paris.

X-rays changed medical practice throughout the last century. Cinema revolutionized entertainment and became a new form of art. Films are now used in the education of tomorrow’s doctors, exposing them to the humanities in addition to rigorous scientific training. A wide range of human experience, including suffering and illness, has been depicted in cinema.

In the early days, films were short, silent, and black-and-white. Cinematic pioneers included George Melies in France and D.W. Griffiths in the US. The physical comedies of Buster Keaton and Charles Chaplin eventually gave way to include more serious subjects. With the advent of sound in the 1920s and color a decade later, films remained an important source of entertainment, but also a medium to explore important social issues. As censorship relaxed in some countries, cinema also became a way to tackle serious, controversial subjects.

The history of medical progress can be documented through the study of cinema. Films with medical themes enable us to vicariously experience the human condition with more empathy. Physicians, surgeons, and psychiatrists are commonly portrayed in films, although pathologists, anesthetists, and radiologists are infrequently represented.

Biopics of medical scientists have provided an insight into scientific discovery. Examples include Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet (1940) about the development of antibiotics and The Great Moment, a 1944 Preston Sturgess film that chronicles William Morton’s discovery of anesthesia. Mervyn Le Roy’s film Marie Curie from 1943 with Greer Garson is another fine example of the genre. It was based on the 1938 biography by her younger daughter Eve Curie.

Not all films portray research or medical ethics favorably. The 1978 film Coma based on Robin Cook’s 1977 novel of the same name is a good example of malfeasance and medical misconduct. The ultimate “mad scientist” story must be Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus, based on Mary Shelley’s 1918 Gothic novel. The story has been told many times in film, including an early version from 1910 produced by Thomas Edison and the classic Hammer production from 1957, The Curse of Frankenstein.

Family doctors were portrayed as early as the silent movie era, as in the little seen D.W. Griffith production of The Country Doctor made in 1909. A fine early twentieth-century portrayal by Trevor Howard of an emotionally reserved British country doctor is seen in David Lean’s 1945 film Brief Encounter based on the play by Noel Coward.

Idealistic physicians were shown in films like The Citadel, directed by King Vidor in 1938 and based on A.J. Cronin’s semi-autobiographical novel about a young doctor working in a Welsh mining community who struggles to enforce his high ethical standards. It is claimed this book had an influence on the creation of the British National Health Service in 1948.

A similar type of idealistic physician is portrayed in Ibsen’s famous play The Enemy of the People, which was made into a film with Steve McQueen in 1978 and a later version in 1990 by the Bengali director Satyajit Ray titled Ganashatru. The story concerns Dr. Stockman, who is unaffected by the corruption around him, follows his conscience, and does what is right in spite of the adverse consequences of his actions. It remains a salutary tale today, more than a century after it was penned by Ibsen in 1882.

Heroic surgeons have been the subject of many films. An arrogant surgical stereotype was portrayed by Alec Baldwin in the 1993 film Malice, including the declaration: “Let me tell you something. I am God.” Not all portrayals of surgeons are unsympathetic. A more empathetic surgeon was depicted in the 1991 film The Doctor, where a surgeon played by William Hurt develops a disease himself, enabling him to acquire the empathy he previously lacked.

A science fiction film from 1966, Fantastic Voyage directed by Richard Fleischer and adapted by David Duncan from a story by Jerome Bixby and Otto Klement, depicts a miniaturized vessel inserted into the bloodstream of a patient who had a stroke so that the miniaturized doctors could break up the clot in the brain. Who would have imagined, half a century later, that radiologists with their catheters would be able to do this procedure non-invasively without the need for miniaturization!

Psychiatrists have had plenty of exposure in films, ranging from the wacky psychiatrist Dr. Fritz Fassbender played by Peter Sellers in Clive Donner’s 1965 film What’s New Pussycat written by Woody Allen, to the mad Hannibal Lector in the 1991 film The Silence of the Lambs. Psychiatry has been much parodied in film, possibly because of people’s inherent discomfort with mental health issues.

Compassion and humanity in medicine were brilliantly shown in the Japanese film Red Beard, a 1965 Akira Kurosawa masterpiece in which Dr. Niide, or “Red Beard,” played by Toshiro Mifune comes to teach a newly-qualified doctor that treating poor patients can lead to greater fulfillment than lucrative private work. This is a film about social injustice, which is highly recommended for all medical students and doctors. The film was based on short stories by the Japanese writer Yamamoto as well as Dostoevsky’s lesser-known novel Humiliated and Insulted.

The oeuvre of the great Swedish film and theater director Ingmar Bergman and his obsession with illness and death provides a feast of study material for doctors. His films included Persona, a 1966 film about a mute patient, and Cries and Whispers, a harrowing 1972 film about a woman dying of cancer and her sisters’ struggle with her dying. In 1957 he directed two films: The Seventh Seal, in which a knight faces Death in a match of chess, one of the great iconic images of the cinema; and Wild Strawberries, where a retired doctor reflects on his life while traveling to receive an award.

In Ikiru, another masterpiece by Kurosawa, a man dying of stomach cancer tries to do something in his last days to give his life meaning. The death of a child is movingly depicted in Satyajit Ray’s 1955 Bengali film debut Pather Panchali set in Calcutta, India. The film features the haunting sitar music of Ravi Shankar as the father realizes his young teenage daughter has died.

Disability is depicted in the 1950 film The Men, in which a young Marlon Brando portrays the frustrations of a paraplegic; the 1931 silent Chaplin film City Lights portrays blindness; and The Elephant Man movingly depicts a man with a disfigurement as a person with feelings like any other.

Films covering mental health issues and addictions are an important genre and have proliferated in recent years. An early example includes Ray Milland’s famous portrayal of alcoholism in Billy Wilder’s 1945 film The Lost Weekend; a more modern take includes Nicholas Cage in Leaving Las Vegas in 1995. Frank Sinatra in 1955 portrayed a drug addict in Otto Preminger’s The Man with the Golden Arm and more realistic depictions can be seen in films like Trainspotting from 1996. In 1975 the Oscar-winning film One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest was one of the first to realistically portray patients in a psychiatric hospital. Peter Brook in his 1967 Marat Sade also dealt with insanity. Schizophrenia was the focus of the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind and neuroses are portrayed in several films of Woody Allen such as Annie Hall and Interiors. Films such as Florian Zeller’s 2021 Oscar winner The Father adapted from his play have made Alzheimer’s disease an important subject for the cinema.

Cinema has provided a new art form through which the vicissitudes and complexities of human life can be explored and analyzed. It also serves as a mirror reflecting the human condition and the society in which we live, and empowers us all to be better human beings.

ARPAN K. BANERJEE, MBBS (LOND), FRCP, FRCR, FBIR, qualified in medicine at St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School, London. He was a consultant radiologist in Birmingham from 1995–2019. He served on the scientific committee of the Royal College of Radiologists 2012–2016. He was Chairman of the British Society for the History of Radiology from 2012–2017. He is Chairman of ISHRAD and adviser to Radiopaedia. He is the author/co-author of numerous papers and articles on a variety of clinical medical, radiological, and medical historical topics and seven books, including Classic Papers in Modern Diagnostic Radiology (2005) and The History of Radiology (OUP 2013).

Leave a Reply