Vicent Rodilla

Alicia López-Castellano

Valencia, Spain

|

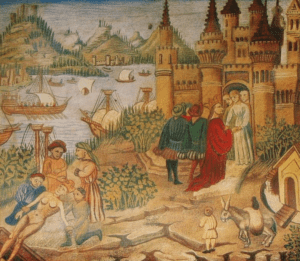

| Figure 1. A miniature from Avicenna’s Canon representing the Salernitan Medical School. Source |

The first medical school in the Western world is thought to be the Schola Medica Salernitana (Figure 1), which traces its origins to the dispensary of an early medieval monastery.1 The medical school at Salerno achieved celebrity between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, before it was overshadowed by universities at Bologna (1088), Montpellier (1220), Padua (1222), and particularly nearby Naples (1224). Contrary to common belief, women of this era had roles not solely as wives, mothers, and nuns, but also practiced medicine and surgery as fully titled physicians.2 Women who worked as practitioners, teachers, and authors of medical texts at the Medical School of Salerno were collectively named Mulieres Salernitanae (The women of Salerno).

The most prominent and well-known of these women is Trota de Ruggiero, but others include Abella Salernitana, Rebecca Guarna, Mercuriade, and Costanza Calenda. Their names are recorded in the Collectio Salernitana, a five-volume collection of previously unpublished documents and medical treatises from the Salerno Medical School published between 1852-1959.2,3

Very little is known about Abella Salernitana (also known as Abella de Castellomata) other than she taught about black bile (madness) and was the author of two texts: De atra bili (On black bile) and De nature seminis hominis (On the nature of the seminal fluid), which are no longer in existence.4

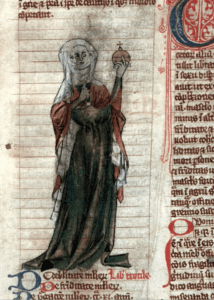

Both Rebecca de Guarna in the 1200s and Mercuriade in the fourteenth century were students and later teachers at Salerno and authored treatises mentioned in Collectio Salernitana.3 Rebecca Guarna wrote De urinis, which included instructions for diagnosis using samples of urine (Figure 2). She is also the author of two other books: one on fever, De febribus, the other on the embryo, De embrione. Mercuriade wrote treatises on unhealthy fevers (De febre pestilenti), on treatments (De curatione), and on ointments and perfumes (De unguentis).4

|

|

Figure 2. A drawing showing a standing female healer clothed in red and green with a white headdress, holding up a urine flask to which she points with her right hand. From: Miscellanea medica XVIII, Published: Early 14th century, Folio 65 recto (=33 recto), London, Wellcome Library, MS 544. Source. |

Costanza Calenda, the daughter of a medical professor at Salerno and Naples, is considered to be the first woman to have earned a doctorate in medicine from Naples University around 1422.4 No written works by Calenda are still in existence, although she is known to have lectured ex-cathedra at Naples University.5

The best-known of the Salernitan women is undoubtedly Trota (or Trocta) de Ruggiero. Born around 1050, she became a renowned physician and professor (magistra) at Salerno and authored several medical texts. She was married to Giovanni Platerarius, a distinguished physician at the Salernitan Medical School, and was the mother of two sons, Giovanni and Matteo, both physicians and professors (Magistri Platearii) at Salerno.6 Trota de Ruggiero wrote a book about female ailments, De passionibus mulierum ante in et post partum (On women’s diseases before during and after birth), known as the Trotula major, which according to some scholars is the first major treatise on gynecology.2,5 This book has sixty-three chapters on topics such as menstruation, conception, pregnancy, birth, and general diseases. She was very advanced for her time as she dealt with birth control, looked for causes of infertility not only in women but also in men, and stressed the importance of personal hygiene, exercise, and balanced nutrition.4,7,8

Trota de Ruggiero also made important contributions to dermatology and cosmetic science. In De ornatum mullierum (On women’s cosmetics), also known as the Trotula minor, she describes detailed formulas for cosmetic use and for the treatment of skin ailments. Some of the ingredients she mentions are still used today in dermatology and cosmetics.6,9

It seems, however, that the extant copies of Latin originals or vernacular translations known as De curis mullierum (On treatments for women), also known as The Trotula (the little works of Trota), are an ensemble of texts by three different authors, although some parts are originals by Trota de Ruggiero.3,10 It has been suggested that Georg Kraut in 1544 rearranged the texts as if they had been written by a single author.10 In the twentieth century, John F. Benton, a historian at the Californian Institute of Technology, discovered the text in a thirteenth-century manuscript in Madrid, and Monica H. Green, a medieval history professor at Arizona State University, discovered a partial copy of the manuscript in Oxford.3,10 For both of them, Trota’s authentic work is the Practica secundum medicine (Practical medicine according to Trota), which covers ailments such as fevers, wounds, and internal diseases that are not specific to women.3

|

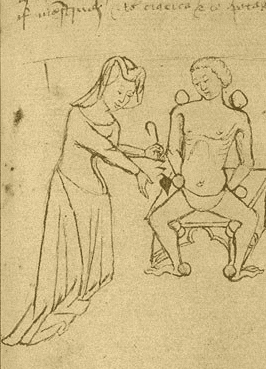

| Figure 3. Medieval female physician practising bloodletting. She is making cuts to the patient with a sort of lancet. (From an early 15th century English manuscript, The British Library). Source. |

Trota was a renowned physician, whose fame spread to France, England, and Northern Europe where copies of her books circulated in Latin or were translated to other languages. Anecdotally, she has also been described as one of the most beautiful women of her time and was held in such high esteem that at the time of her death in 1097, her funeral procession stretched for over three kilometers along the streets of Salerno.6

Women have been recorded practicing all branches of medicine and surgery (Figure 3) during the Middle Ages,3,4 something that would not be seen again until the nineteenth century.

References

- Pasca M. The salerno school of medicine. Am J Nephrol. 1994;14(4-6):478-482. doi:10.1159/000168770

- Della Monica M, Mauri R, Scarano F, Lonardo F, Scarano G. The Salernitan school of medicine: Women, men, and children. A syndromological review of the oldest medical school in the western world. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2013;161(4):809-816. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35742

- Green M. Women’s medical practice and health care in medieval Europe. Signs (Chic). 1989;14(2):434-474. doi:10.1086/494516

- Whaley L. Women and the Practice of Medical Care in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1800. Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2011.

- Bayon HP. Trotula and the Ladies of Salerno: A Contribution to the Knowledge of the Transition between Ancient and Mediaeval Physick. Proc R Soc Med. 1940;33(8):471-475..

- Bifulco M, De Falco DD, Aquino RP, Pisanti S. Trotula de Ruggiero: The Magistra mulier sapiens and her medical dermatology treatises. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(6):1613-1616. doi:10.1111/jocd.12882

- Bifulco M, Ciaglia E, Marasco M, Gangemi G. A focus on Trotula de’ Ruggiero: A pioneer in women’s and children’s health in history of medicine. J Matern Neonatal Med. 2014;27(2):204-205. doi:10.3109/14767058.2013.804056

- Ferraris ZA, Ferraris VA. The women of salerno: Contribution to the origins of surgery from medieval Italy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64(6):1855-1857. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(97)01079-5

- Cavallo P, Proto MC, Patruno C, Sorbo A Del, Bifulco M. The first cosmetic treatise of history. A female point of view. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2008;30(2):79-86. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2494.2007.00414.x

- Green MH. In search of an “Authenic” women’s medicine: the strange fates of Trota of Salerno and Hildegard of Bingen. Dynamis. 1999;19:25-54. doi:10.4321/106141

VICENT RODILLA, PhD, is a lecturer at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera in Valencia, Spain. Amongst other subjects, he teaches the history of medicine and an introduction to epidemiology to medical students. He has an interest in the visual arts and their representation of medicine.

ALICIA LÓPEZ-CASTELLANO, PhD, is professor of Pharmaceutical Technology and Medical Devices at Universidad CEU Cardenal Herrera in Valencia, Spain. Besides Pharmaceutical technology she also teaches health products and cosmetics.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Women in Medicine

Leave a Reply