Stephen Martin

Thailand

Thomas Richardson Colledge (1797-1879) was an ophthalmic surgeon who practiced in Macao, China, for a quarter of a century in the late Regency era. Colledge’s daughter, Frances Mary Martin (1847-1918) wrote a brief biography of him in 1880.1 It is an absorbing and touching account, and important in relation to an extraordinary medical painting by George Chinnery (Fig 1). Although Colledge’s missionary writing has survived,2 Martin’s biography and Chinnery’s painting remain the richest record of his medical work.

Colledge

In 1818 Colledge was appointed Civil Surgeon in Macao on the advice of King George IV’s surgeon, Sir Astley Cooper. Colledge established “with the help of friends, an Ophthalmic Hospital for the Chinese,” which was the first hospital of western medicine in China.3 He co-founded and was president of The Medical Mission in China for forty years, later carrying on this work back in England. Frances Martin noted: “His one assistant was a half-Chinese, half-Portuguese named Afun, a Roman Catholic, and the best man, my father used to say, he ever knew.” Colledge worked in China when there was a marked contrast in medical training, regulation, and practice between China and the west.2 While there were broad restrictions on what foreigners could do, Macao was open to foreigners who conducted business and their families,4 which supported the work of both Colledge and Chinnery.

Chinnery’s painting was commissioned by the East India Company (EIC) at a cost of £500.00, which was a huge sum of money but was the going rate for a master canvas. The painting was shipped to England on completion and a print of the canvas engraved by William Daniell in 1834, entitled “Thomas Colledge Esq’re Member of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, and Surgeon to the British Factory in China, attending at his private Opthalmic (sic) Infirmary in Macao.”5 Many decades later, the painting was donated by an EIC Director to the Chinnery family and came to Salem, USA by descent.

Chinnery

George Chinnery (1774-1852) was a precocious talent, first exhibiting at the Royal Academy in London when he was seventeen. He started professionally by painting miniatures.4 He was troubled with psychiatric difficulties across the bipolar spectrum, with repeated episodes of vast overspending, restlessness, anger, and impulsivity,6 alternating with hypochondriasis and melancholia.4 Sir Charles D’Oyly drew Chinnery in late middle age, dancing vigorously with a wild expression.7 Chinnery twice left his family, heading for India in 1802 and next for China. He spent half a century in Asia and is buried in Macao.

There is no evidence that Chinnery’s mental health ever impaired his art for long. He adopted Sir Thomas Lawrence’s romantic swagger form, but isolated in Asia, he continued creating quasi-photographic compositions of the Enlightenment well into Victorian times, with rich use of his sitter’s symbols and emblems. He channeled his manic energy into many different types of media on paper and canvas. He had a prolific output of drawings of Bengali and Cantonese life, which leave no doubt as to his fondness for Asia.7 Ellis Waterhouse8 described him as painting “with considerable brilliance and charm.”

The painting

In Chinnery’s commissioned painting of Colledge, a Chinese female patient sits on a William IV chair. Her pretty coral earrings tastefully match the finial of her parasol. Her spectacle frames are the same style as those in a self-portrait by Chinnery.9 Afun shows energetic movement and an intelligent, attentive expression. Colledge delicately touches the patient’s head while engaging with Afun, and a boy holds the eye chart (Fig 2). The table, also William IV, has a gadrooned pedestal with six books and an instrument case. Chinese and Indian furniture makers at the time copied English fashions. A leather binding embossed with gilded Royal arms lies on the floor.

Several maps show the hospital above Macao’s Inner Harbor, which is seen under a banana leaf and tree in the background. This is a similar backdrop to a portrait of Colledge’s American successor, Dr. Peter Parker, who was also portrayed with a Cantonese assistant by the Chinese artist Lam Qua. Another interesting Chinese-American interplay is that at the time of the painting Afun’s son, Ayok, had emigrated to New York to work for Harriet Low, a school friend of Colledge’s American wife, Caroline Matilda Shillaber of Salem.10

On Colledge’s consulting room wall is a painting of a Cantonese shore, with a small fishing boat in the central foreground and a fisherman’s hut. The building to the right has an angled corner, typical of Chinese shops, allowing carts to turn with less risk of hitting the building or any customers. There is no strong symbolism in the picture, just a love of the area. It looks like a small landscape by Chinnery. He had also painted a personal commission for the Colledges’ wedding in 1833,11 a richly-colored canvas of Colledge, his wife Caroline playing the harp, and their dog.12

Ophthalmology

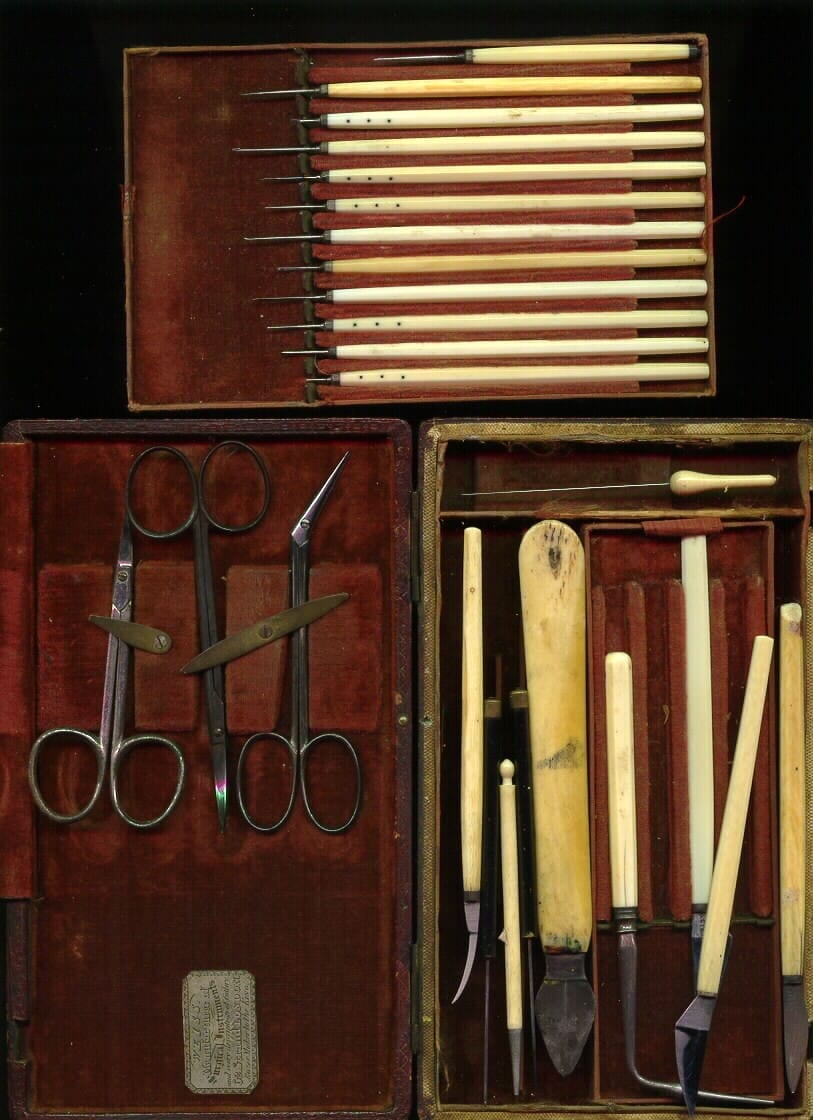

As portrayed in the painting, Colledge’s instrument box is sophisticated (Fig 3). The lid contains four sets of fine forceps and scissors and, in the center, speculum forceps for opening eyelids. The base of the box holds about ten ivory-handled instruments, likely to be hooks, knives, needles, and spoons. Whilst there are many additions to the modern armamentarium of ophthalmic surgical instruments, a version of Colledge’s set is still in use in the modern operating theatre. The ophthalmoscope was invented later, in 1851. A set of similar instruments by John Weiss (Fig 4) survives from Colledge’s time. The Weiss company still makes ophthalmic instruments today, having traded from 1787. The label address in Figure 3 is 62 The Strand, London, the location of their workshop from 1836 to 1841. Weiss could well have shipped out Colledge’s instruments to Macao.

The patient who is waiting has a grubby post-op bandage over his eyes, which perhaps does not bode so well prognostically as the cheerful scene in the right-hand side of the picture.

In the mid nineteenth-century, test letter charts were used by many hospitals. They were standardized by Snellen in the Netherlands in 1862. The current position of the Museum of the College of Optometrists is that it was Snellen’s work which generated foreign language test charts.13,a This makes Colledge and Afun notable pioneers of optometry charts with their own Chinese versions; Afun’s involvement is a strong likelihood. Colledge’s spoken Cantonese was probably competent, but we do not know whether he could write it, a much more difficult achievement. Chinnery’s transcription of the Chinese characters for simple words looks accurate.

Colledge obtained his medical degree in Aberdeen about six years after the painting, before settling in 1844 in a new villa, Lauriston House, (Fig 5) which still stands in Cheltenham. Having surgical experience before obtaining a medical degree at a later date echoes the physician versus barber surgeon divide of the eighteenth century. Much had happened in the regulation of medicine while Colledge was away, including the UK’s Anatomy Act of 1832, partly led by Astley Cooper.

Colledge’s daughter wrote about the “despair” of the London medical community that after returning to England he was in Cheltenham and not amongst them, but settling in the English provinces makes sense. It meant less competition and resembled the elegant, small-town life around the port of Macao.

Significance

It is striking that the EIC had a picture of racially-integrated medical philanthropy in China. While colonialism must always be analyzed head-on by historians, John Cavell’s approach14 that “colonisation was not a monolith” is important to learn the many-faceted lessons of that time. Colledge was free to sail to Macao after the peace of the Treaty of Paris, bringing needed medicines. He appeared to have had good working relationships with his patients and his assistant Afun. After his return to England, patients who had known him in Macao even moved to live near him in Cheltenham. When Colledge’s family sailed out of Macao, “every European was onboard ship to wish him ‘bon voyage,’ and the sands and rocks around crowded with Chinese.”

References

- Frances Mary Martin, née Colledge. Thomas Richardson Colledge. Born 1797. Died 1879. Looker-on Printing Company, Cheltenham, 1880. Archive.org

- Fu L. The protestant medical missions to China: Dr Thomas Richardson Colledge (1796-1879) and the founding of the Macao Ophthalmic Hospital. J Med Biogr. 2013 May; 21(2): 118-23.

- Ravin J G. Thomas Colledge A Pioneering British Eye Surgeon in China. Arch Ophthalmol. Oct 2001;119 (10): 1530-1532.

- Carr A. George Chinnery 1774-1852. Arts Council Gallery, London 1957.

- http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O755565/portrait-of-thomas-richardson-colledge-print-daniell-william/

- Foskett D. British Portrait Miniatures. Methuen, London, 1963.

- Conceição A Jr. George Chinnery. Macau. Galeria de Museu Luís de Camões. Macao, 1985.

- Waterhouse E. The Dictionary of British 18th-Century Painters. Antique Collectors’ Club, Suffolk, 1981.

- npg.org.uk/collections/search/portraitExtended/mw01285/George-Chinnery

- Davis N. The Chinese Lady. Afong Moy in Early America. OUP, 2019. Reviews the American Harriet Low’s account of Afun, Ayok and Caroline Shillaber.

- Tillotson G H R. Fan Kwae Pictures. The Hong Kong Bank Art Collection. Spink and Son Ltd, London, 1987.

- HSBC Collection, Hong Kong.

- https://www.college-optometrists.org/the-college/museum/online-exhibitions/virtual-ophthalmic-instrument-gallery/test-charts.htm

- Carroll J M. Canton Days. British Life and Death in China. Rowman and Littlefield, London, 2020. P 305.

Note

- Graham Kyle, FRCS Ed, kindly commented on discussing Harriet Low’s observation that the patient had recovered from blindness: “The trial frame with correcting lenses is being raised onto the patients brow, and a card to test near vision is being picked up, suggesting that the patient needed lenses for distance vision, but not for near; ie was short-sighted. Post-operative cataract patients in those days (prior to lens implants) were very long sighted and required strong (thick) lenses for distance vision, and even stronger lenses for near. If the patient were completely blind, and had had her sight restored, then the likely diagnosis was either optic nerve inflammation which spontaneously recovered (as does not infrequently occur), or hysterical blindness.”

Picture credits

- Fig 1. Reproduced here with the kind permission of the Peabody Essex Museum. Gift of Cecilia Colledge, in memory of her father, Lionel Colledge, FRCS, 2003. M23017.

- Fig 4. Accessed at medicalantiques.com and reproduced here with the kind permission of Douglas Arbittier MD MBA.

- Fig 5. Google Maps, 2020.

STEPHEN MARTIN is a retired UK neuropsychiatrist, Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society, and honorary professor of psychiatry at Chiang Mai University Medical School, Thailand.

Leave a Reply