Jayant Radhakrishnan

Darien, Illinois, United States

|

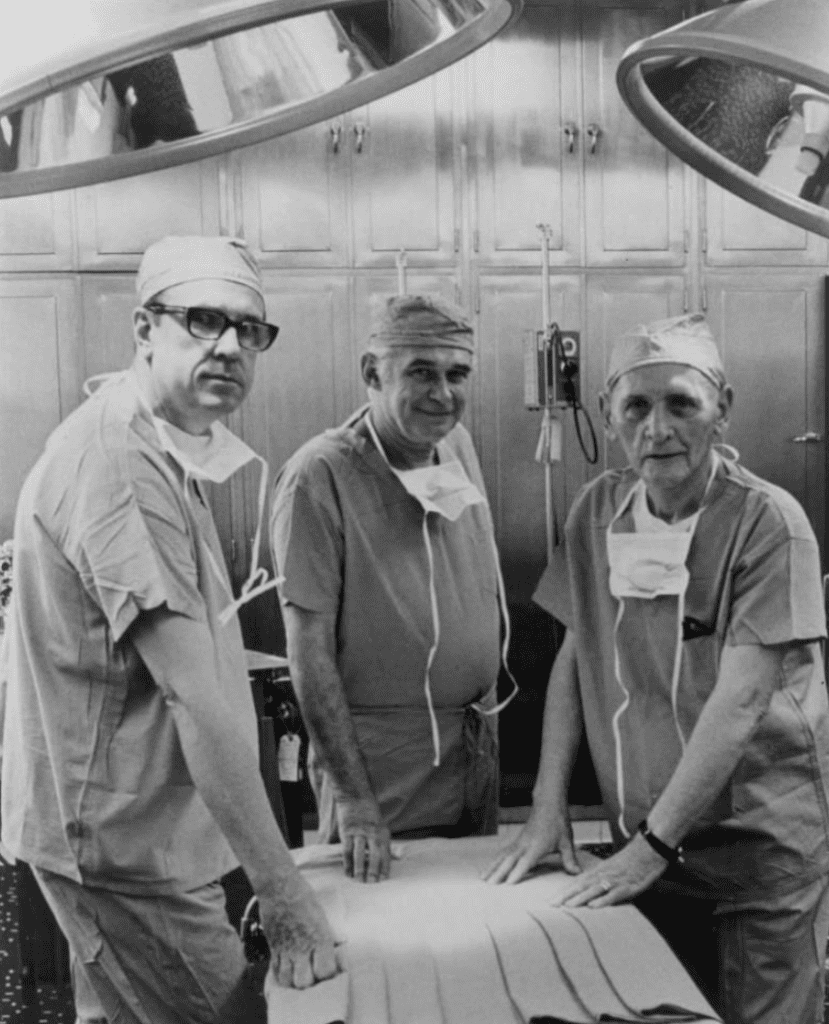

| The first kidney transplant was performed by Dr. Richard Lawler, Dr. James West, and Dr. Raymond Murphy at Little Company of Mary Hospital, Evergreen Park, IL. Photo courtesy of OSF Little Company of Mary Medical center. |

Dr. Joseph Murray deservedly received the Nobel Prize in 1990 for his magnificent pioneering work in the field of renal transplantation.1 However, it is not widely known that religious sisters from the congregation of the Little Company of Mary also deserve much credit for their support of renal transplantation in those early days, when transplants failed more often than they succeeded.

Three Little Company of Mary sisters—Mother Patrick, Sister Veronica, and Sister Philomena—first came to Chicago in 1893 from Rome. Initially they cared for the sick on the south side of Chicago by traveling to people’s homes. Realizing the need for a hospital, they took a chance in the middle of the Depression and bought a tract of swampy, isolated land in Evergreen Park, Illinois and established a 150-bed hospital in 1930. When the hospital opened, its entire staff consisted of twelve physicians and the sisters.

Attempts at transplanting kidneys in animals and humans since the turn of the twentieth century had met with limited success.2,3 In human renal homotransplants in the 1930s and 40s, the renal vessels were anastomosed to the femoral vessels or the brachial artery and cephalic vein, for reasons related to the fact that failure and removal of the transplanted kidney was anticipated.2,3 Intraabdominal placement of the kidney was considered a very risky step. The doctors at Little Company of Mary Hospital had practiced this procedure many times on animals and cadavers. They crossed a major barrier when Drs. Lawler, West, McNulty, Clancy, and Murphy carried out the first intraabdominal human renal transplant in the world on June 17, 1950 (Figure 1).

The transplant recipient was a forty-four-year-old white woman named Ruth Tucker (Figure 2), whose polycystic kidneys were minimally functional. Her kidney donor was a forty-nine-year-old white woman with the same ABO and Rh blood types who had exsanguinated from esophageal varices secondary to cirrhosis of the liver. After removing the native, almost nonfunctional left kidney, the surgeons placed the transplanted kidney in the left renal fossa and the donor’s renal vessels were anastomosed to those of the recipient. Upon removal of the clamps “the color of the kidney changed from bluish-brown to reddish-brown.”4 The surgeons carried out a stented ureteroureterostomy for urinary drainage. The serum creatinine dropped from 2.3 mg% to 1.2 mg% over the next three months, and at fifty-two days after surgery an intravenous infusion of indigo-carmine dye was excreted by both the transplanted and native kidneys. A retrograde pyelogram on the sixty-second postoperative day demonstrated a partial stricture at the uretero-ureteral anastomosis, which they planned to revise at a later date. Based on laboratory tests on January 25, 1951 (seven months after the transplant), the kidney seemed to be functioning, but on April 1, 1951, more than nine months after transplantation, there was no urine output, although the kidney still looked viable upon exploration.5 Even though the transplanted kidney failed, it gave the remaining native kidney time to recover and the patient lived four more years.

|

| Ruth Tucker, 44, pictured above, of Jasper, Indiana was the recipient of the first kidney transplant. For over four years after the operation, she resumed an active lifestyle, and died of coronary occlusion unrelated to the transplant. Photograph courtesy of OSF Little Company of Mary Medical Center. |

It is intriguing that Drs. Lawler and West were both on the staff of the Stritch School of Medicine of Loyola University and the Cook County Hospital, yet they chose to operate at Little Company of Mary Hospital. Their decision is best explained in James West’s own words: “what we needed was the trust of the sisters. The sisters of Little Company of Mary knew us well enough to trust us with doing this radical, bizarre operation.”6 West pointed out that neither the surgeons nor the hospital notified anyone that they had carried out the transplant since they wanted to be certain the patient survived the procedure. West further stated, “This was very controversial, even in the medical community. We had many doctors who supported it, but many were against it. The clergy in particular opposed this procedure – they were opposed to the idea that you could take tissue from someone who was dead and put it in someone who was alive and it would come back to life. It was like, once it was dead it should stay dead.”6

Although neither the hospital nor the surgeons publicized what they had accomplished, a relative of the patient informed the media and created a worldwide frenzy. The media wanted interviews, patients with kidney problems wondered whether they were candidates for a transplant, and physicians wished to be able to observe and learn from future transplants. However, neither Lawler nor West ever participated in another renal transplant. When asked, Lawler is reported to have said at his retirement in 1979, “I just wanted to get it started.” He died at Little Company of Mary Hospital on July 26, 1982.7

West retired form surgery in 1981 and helped launch the Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage, California on October 4, 1982 along with the former First Lady of the United States. He was affiliated with the center until he retired in 2007 at the age of ninety-three. He died on July 24, 2012 at his home in Palm Desert, California.8

At a time when organs from one human being had never been successfully transplanted into another, and immunosuppression and tissue typing were unknown, these remarkable nuns were so convinced of the possible future benefits of the procedure that they were willing to take on the religious, medical, and political establishments, even if the patient succumbed as a result of the operation. When news of this successful operation leaked out, it resulted in great public interest around the world and surgeons took to the task in earnest. The first long-term success in renal transplantation was when Dr. Murray transplanted a kidney between identical twins on December 23, 1954.9

References

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1990. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2020. Thu. 12 Mar 2020. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1990/summary/’

- Hume DM, Merrill JP, Miller BF, Thorn GW (1955). Experiences with renal homotransplantation in the human: report of nine cases J Clin Invest 34;327-382.

- Matevossian E, Kern H, Huser N, Doll D, Snopok Y, Nahrig J, Altomonte J, Sinicina I, Friess H, Thorban S (2009). Surgeon Yurii Voronoy (1895-1961)-a pioneer in the history of clinical transplantation: in memoriam at the 75th anniversary of the first human kidney transplantation. Transplant International 22;1132-1139.

- Lawler RH, West JW, McNulty PH, Clancy EJ, Murphy RP (1950). Homotransplantation of the kidney in the human. A preliminary report. JAMA 144;844-845.

- Lawler RH, West JW, McNulty PH, Clancy EJ, Murphy RP (1951). Homotransplantation of the kidney in the human. Supplemental report of a case. JAMA 147;45-46.

- Martin M (2004). Making-and remembering-transplant history. The Catholic New World (Newspaper for the Archdiocese of Chicago). September 2004.

- RH Lawler, pioneer of kidney transplants (1982). The New York Times obituary. July 27, 1982

- Nelson VJ, Los Angeles Times (2012). Dr. James West dies at 98, a founder of Betty Ford Center. Chicago Tribune August 5, 2012.

- Merrill JP, Murray JE, Harrison JH, Guild WR (1956). Successful homotransplantations of the human kidney between identical twins. JAMA 160;277-282

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP, completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending pediatric surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago from where he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.

Spring 2020 | Sections | Nephrology & Hypertension

Leave a Reply