Julius P. Bonello

Adam Awwad

Peoria, Illinois, United States

Since the first wheel rolled out of the mouth of a cave, sports have been a staple in our social fabric. From throwing balls to picking up sticks, from tug-of-war to wrestling, from chess to football, and from horse racing to car racing, sporting events have united humans. Even if your favorite competitor loses, frivolity reigns, but sometimes the old cliché “It’s all fun and games until someone loses an eye” becomes reality. Such was the case on June 30, 1559, when during a festival to honor a treaty and a daughter’s marriage, tragedy struck. A forty-year-old father of ten, husband to an adoring wife, and the reigning King of France lay mortally wounded from an injury sustained during a sporting event.

Henry II was born outside of Paris on March 31, 1519, the second son of Francis I, King of France. He had a normal childhood until the age of seven when he and his brother were sent to Madrid in exchange for his incarcerated father, who had lost a major battle to Spain. At the age of eleven, he and his brother were allowed to return to Paris. Unable to speak fluent French, he was assigned a mentor, the beautiful thirty-year-old Diane de Poitiers. At first it was purely academic, but five years later Henry and Diane would start a lifelong romantic affair. When his elder brother Francis died in 1536, Henry became the heir apparent to the throne. He succeeded his father on his twenty-eighth birthday and was crowned King of France on July 25, 1547.

At the behest of his father, Henry had married Catherine de Medici at the age of fourteen. Childless for the first ten years, both Henry and Catherine sought medical advice and, after examination, were told to alter their sexual positions. Over the next twelve years, Catherine and Henry had ten children.

During his relatively short twelve-year reign (1547-1559), Henry continued both his father’s persecution of Protestants and France’s involvement in the Italian Wars (1515-1559).

Henry was rather draconian in his persecution of the Protestants. He would have Protestant ministers burned at the stake or suffer amputations of their tongues for speaking heresies. The King strictly prohibited the sale or printing of any book considered heretical by the faculty of theology at the University of Paris. Authors or printers, if convicted, could face the loss of their property or even death.

His marriage to Catherine was to contain a dowry consisting of money and the acquisition of three cities in Italy promised by her uncle, Pope Clement VII. However, upon the Pope’s death one year later, the dowry was annulled and the cities stayed in the Kingdom of Savoy. Wanting more land in Italy, Henry declared war against the Holy Roman Empire in 1551. His army was successful in taking the Duchy of Lorraine in what is now northeastern France, but was easily defeated in the Battle of Marciano (1553) in northern Italy. With a defeat by the Spanish at Saint Quentin and England entering the war, Henry was forced to surrender and sign the Peace of Cateau-Cambresis.

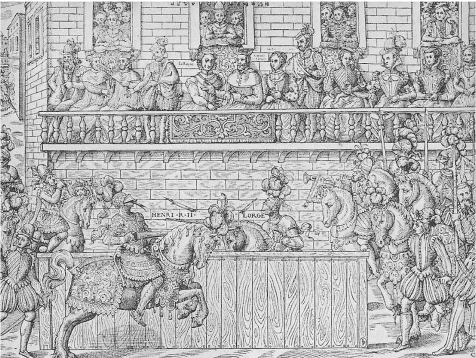

The treaty, signed by King Henry II of France, Philip II of Spain, and Elizabeth I of England in the spring of 1559, put an end to the Italian Wars. The peace was cemented by two weddings: Henry II’s daughter Elizabeth to Philip II of Spain, and Henry’s sister Margaret to the reigning Duke of Savoy. The celebration at the signing included eating, drinking, and sport, specifically jousting.

Jousting was originally popular in the eleventh century as a way for knights to train for combat, but evolved into a form of entertainment thanks to the introduction of the longbow and the arquebus. By the mid 1500’s, jousting had become the sport of kings, enjoyed by the immensely wealthy who could afford the armor (100 pounds per rider) and horses.

Jousting required two warriors dressed in armor, mounted on horses and riding full tilt toward each other while holding a long pointed wooden spear called a lance. The lance, used to hit the opponent in the right shoulder, had enormous impact in clashes up to twenty-five miles per hour. A strike that hit its mark would earn the competitor a point. They would face each other again until the winner unseated the opponent from his horse.

The forty-year-old Henry was an accomplished equestrian and jouster. The King’s opponent was Gabriel Montgomery, captain of Henry’s Scots guard. Gabriel earlier that day had unseated Henry in another jousting event. Catherine thought that Henry was too tired and should retire from the field. However, Henry insisted he could perform once more.

Perhaps it was the overall happiness of the event or maybe a little too much “taste of the grape” that clouded Catherine’s memory, for she had been warned earlier. Nostradamus (1503-1566), the famous astrologer employed by young Catherine to help in her quest for motherhood, later in his life began to write quatrains, short four-line prophecies. His book of 942 quatrains, published in 1555, has rarely been out of print since his death. In one famous quatrain, he wrote that Henry should not engage in either combat or a joust: “The Lion shall overcome the old on the field of war in a single combat (duele); He will pierce the eyes in a cage of gold. This is the first of two lappings, then he dies a cruel death.”

Ignoring his wife’s wishes and possibly being slightly concussed, Henry donned his armor, adorned himself in the colors of his mistress, and entered the arena. Henry pulled down his visor, but in his haste forgot to buckle it. When the trumpets sounded, both opponents galloped towards each other. Both lances hit their mark and shattered. Gabriel, taught to drop his lance to prevent further injury, forgot. His splintered lance slid up to Henry’s helmet, forced the visor open, and buried its splintered end into the King’s right eye socket.

Henry managed to stay on his horse and remain conscious, but his nobles helped him to the ground. He had profuse bleeding from his right eye. Physicians tried to remove the splinters in the arena, but it proved to be too painful. He attempted to walk on his own, but fainted twice. Attendants carried the King inside and placed him on bed rest. Devastated by the injury, Gabriel begged for forgiveness and asked the King to cut off his head and hand. Henry refused and pardoned him. Nonetheless, that night Gabriel could not rest and quickly left Paris.

Despite the heroic efforts of all involved, Henry II would die in ten days. His fatal injury, however, brought together two of the most famous doctors of the sixteenth century: Ambrose Pare, now known as the “Father of Trauma” and already in Henry’s court; and Andreas Vesalius, “Father of Anatomy,” summoned from Brussels to offer medical assistance.

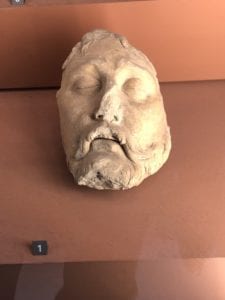

While Pare contemplated a surgical intervention, Henry’s physicians purged him with a potion of rhubarb and bled him of twelve ounces of blood. Pare entertained the idea of trephining, drilling a hole into the skull, but awaited the outcome of an experiment; Catherine had four prisoners decapitated and their heads sent to Pare to re-create the injury. Pare, using Gabriel‘s own shattered lance, thrust the severed heads’ eye sockets to determine the extent of injury. He concluded that the lance did not penetrate the lining (dura mater) of the brain and therefore would not benefit from a trephine. If the King survived, he would lose his eye.

Vesalius arrived three days after the injury. After examining the wound and finding neurologic signs of meningitis, Vesalius felt that the King would not survive. He used the phrase “chironim vulnus,” or the wound will not heal.

The following day, Henry spiked a temperature. This, combined with pus coming from his wound and increasing mental obtundation, were signs of sepsis. Again, both Pare and Vesalius entertained the idea of trephining, but with pus emanating from his wound they both thought it would be superfluous. Over the next three days, his physicians observed bouts of delirium interspersed with frequent sweats and shaking chills. Henry’s left leg and arm stopped moving and he began to experience prolonged convulsions. Despite this overwhelmingly poor condition, Henry was occasionally able to rally enough to make decisions for the country.

On Sunday, July 9, 1559, they made it public that all hope was gone and the bells of Paris were silenced. Again that night trephining was brought up, but when the bandages were removed, they found an overwhelming amount of pus and knew it was hopeless.

On Monday, July 10, Henry took the last sacraments and was pronounced dead about one o’clock in the afternoon

Pare and Vesalius performed an autopsy immediately. They found, as predicted, that the splinters had entered the orbit but did not pierce the skull or the dura mater. They did not see a fracture. According to Pare, a bloody effusion was present between the dura and the inner meninges at the posterior aspect of the cranium, a countercoup injury. Moreover, near the effusion a yellowish cerebral substance had begun to show putrefaction. An abscess had formed.

In 1816, Henry II was reinterred by orders of Louis XVIII after the King’s tomb and corpse were violated during the French Revolution. A detailed description of the skull of Henry II did show a fractured orbital bone. Therefore, it appears that cause of death for Henry II was meningoencephalitis caused by a hematoma of a cerebral contusion initiated by a periorbital fracture. Pare and Vesalius made use of all medical and surgical knowledge at that time. Retrospectively, there would have been no way to save the King from his injuries.

References

- Faria, M. A. (1992). The death of Henry II of France, Journal of Neurosurgery, 77(6), 964-969. Retrieved Dec 13, 2019, from https://thejns.org/view/journals/j-neurosurg/77/6/article-p964.xml

- Dowling, Kamilah A., DNP and Goodrich, James T., MD, PhD, Dsci. Two cases of 16th century head injuries managed in royal European families, Neurosurgical Focus, 41 (1): E2, 2016: 1 – 14.

- Kian Eftekhari MD, Christina H. Choe MD, M. Reza Vagefi, MD, Lauren A. Eckstein MD, PhDd The last ride of Henry II of France: Orbital injury and a king’s demise. Survey of Ophthalmology

Volume 60, Issue 3, May–June 2015, Pages 274-278 - Martin, Graham. The Death of Henry II of France: A Sporting Death and Post-Mortem. Australian Journal of Surgery 2001 vol. 71 318-320.

- Markatos, Konstantinos, Karamanou, Marianna, Arkoudi, Konstantina, Androutsos, Georgios. Henry II of France (1519–1559) and His Death From Meningoencephalitis Following Cranial Trauma, World Neurosurgery Volume 106, October 2017, Pages 442-445

JULIUS P. BONELLO, MD, FACS, has taught students and residents for the last forty-five years at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. He now holds the title of Professor Emeritus of Clinical Surgery. He has eight children and lives in Peoria, Illinois with his wife of thirty-three years.

ADAM AWWAD, BA, is a third-year medical student at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria, where he is co-president of the Health, Humanity, and Society student interest group. His research interests include bioethics and the history of medical science.

Leave a Reply