Bedřich (Frederic) Smetana was one of the major figures of nineteenth century European music. Regarded as the founder of the Czech national school of music, he composed The Bartered Bride opera and the symphonic poem “Má Vlast” (My Homeland) with its beloved Vlatava (The Moldau) melody. Like Ludwig van Beethoven, he composed exceptional music even after he lost his hearing.

Smetana was born in 1824 in a small Bohemian town about eighty miles east of Prague and was the son of an affluent brewer and amateur musician. As a child prodigy he performed in a string quartet at age five, gave a solo piano performance at six, and wrote his first composition at age eight. His early musical training was from his father. As he grew up in a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire where German was the main spoken language, he did not learn Czech until much later in life.

As a teenager Smetana continued to study music, at first against his father’s wishes. Aspiring to become a famous composer, he moved to Prague in 1843, earning a meager living in various positions as a music teacher. In Europe’s 1848 year of revolutions, he was briefly involved in the Bohemian independence movement and fought against the Habsburg troops on the barricades over the Charles River. Subsequently he started a piano school and a music institute in Prague, but finding that his career was not going anywhere, he moved in 1856 to Gothenburg in Sweden.

During his time in Sweden he gave concerts, worked as music conductor, and opened a music school. He made the acquaintance of pianist Franz Liszt, who became his mentor and encouraged him to compose music on a large scale. He began to write some of his later well-known compositions and increasingly achieved professional recognition. He had married in 1848 a young pianist and they had four daughters, two of whom died in infancy of tuberculosis and one of scarlet fever. His first wife also dying of tuberculosis (1859), he married a twenty year old woman in 1860 and had two daughters by her.

Perhaps unrelated to his later hearing problems, he had been in an accident at age eleven when a bottle of gunpowder exploded in his face giving rise to an osteomyelitis of the temporal bone. At age thirty-eight (1862) he first developed a constant ringing in the ears and impaired hearing. He was examined and treated by the most eminent specialists in Paris, but his hearing became progressively worse.

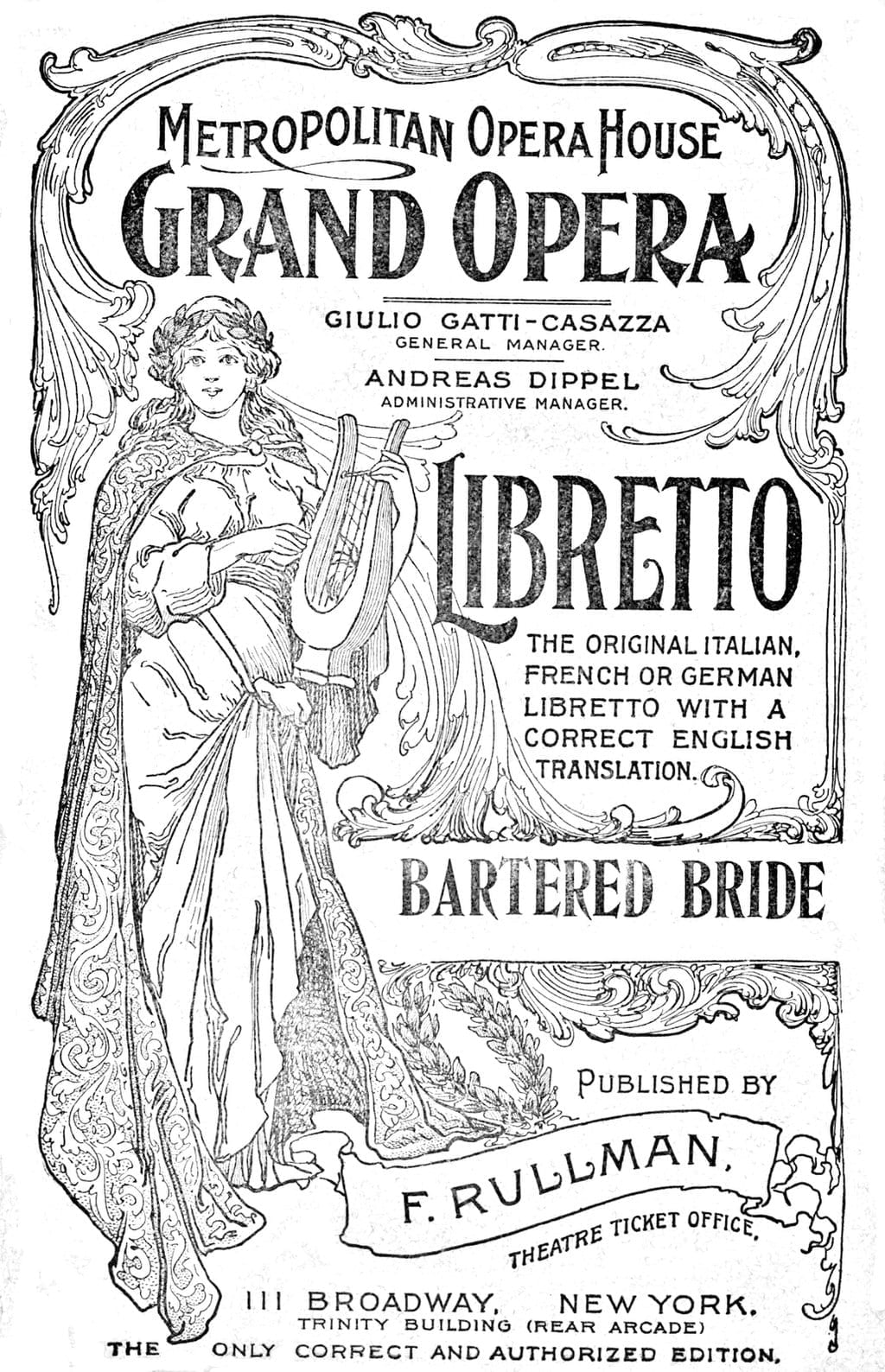

Following the semi-independence of Bohemia in 1861 he returned to Prague, and in 1865 became conductor of the Provincial Theater and briefly its artistic director. In 1866 he produced The Bartered Bride, which established his international reputation. He resigned from his position in 1874 after various political controversies, and also because his health was deteriorating, beginning with a “pus-oozing ulcer” followed by a generalized skin rash as well as by now total deafness.1 He moved to the countryside with his eldest daughter and there was able to compose undisturbed.

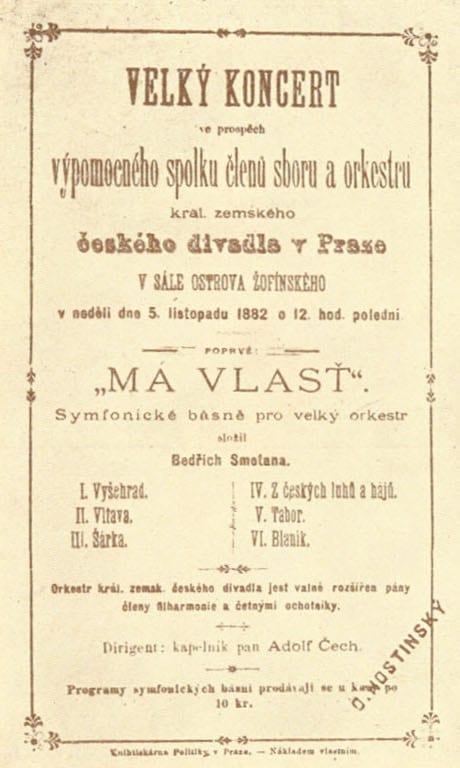

Amongst Smetana’s compositions are two string quartets. His first was subtitled “From My Life,” where its fourth movement is in the form of a rustic dance that breaks off in a whining high E played by the first violin—felt to represent the tinnitus that racked his inner ear and heralded his approaching deafness. The second quartet, his last important work and written in 1882-1883, is considered to be a more troubling representation of his disturbed state of mind toward the end of his life.

Mental symptoms developed in 1881 in the form of confusion, difficulty in speaking coherently, depression, memory lapses, and several episodes of aphasia.1 In early 1884 he began having visual and auditory hallucinations, became incoherent, unable to walk, no longer able to recognize his friends or children, and subject to violent paranoid behavior and rage attacks. Confined to a mental asylum, he died in 1884 at age sixty. His funeral was attended by a large crowd and he was buried as a national hero.

Smetana’s autopsy showed thickening of the meninges due to chronic inflammation, dilatation of the lateral ventricles, and atrophy of the cortex and acoustic nerves, changes accounting for his deafness and compatible with tertiary neurosyphilis or general paresis of the insane. When the body was exhumed about one hundred years later, most but not all authorities agreed with the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Large concentrations of mercury were found in the brain, perhaps the result of treatment, but leaving unresolved the issue whether his earlier auditory symptoms were also due to syphilis.

|

|

|

Reference

- Newmark J, Neurological problems of famous musicians. Journal of Child Neurology, 2009,24:1043, (August).

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply