Philip R. Liebson

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Each year the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology honors a physician “whose scientific achievements have contributed profoundly to the advancement and practice of clinical cardiology.” This award is named after the physician James B. Herrick (1861-1954) who, within a two-year period, presented descriptions that crystallized the focus on two major diseases. Between 1910 and 1912, he discovered and first described the manifestations of sickle-cell disease (now hemoglobin SS) and provided the first definitive description of the clinical manifestations of coronary thrombosis. For many years, sickle-cell disease was known as Herrick’s syndrome.

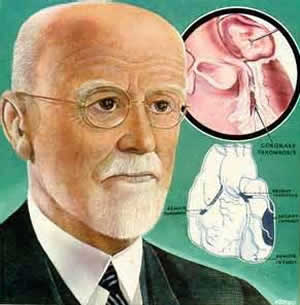

At the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago—known as Presbyterian Hospital when Herrick practiced there—his presence is still felt: the cardiology conference room is named after him, a chair is named for him, and his picture hangs in one of the main conference areas. This last portrays him as an elderly man with a mustache, well-trimmed white beard, and stolid expression. It is ironic that, although he spent over 50 years at the institution, he died less than four months before the first cardiology fellowship was initiated. It was, however, a fitting memorial to the physician who contributed so much to the institution and to cardiovascular medicine.

Herrick was a Chicagoan born and bred. He grew up in Oak Park (a Chicago suburb) and attended the University of Michigan where he graduated in 1882. After teaching for several years in public schools he entered Rush Medical College, receiving his medical degree in 1888. At the time and for many years afterwards, Rush was associated with Presbyterian Hospital. Herrick went into private practice for a few years and joined the staff of Presbyterian Hospital, achieving full professorship at Rush in 1900. Like many clinicians with a bent toward research, he traveled to Europe where he worked with the renowned pathologist Hans Chiara for three months in Prague. Several years later he spent time in a Vienna clinic. His contributions to the medical literature began early. In 1896, for example, he published eleven articles on cardiovascular disease and anemia.1 He continued his education while a professor at Rush by taking courses in chemistry at the University of Chicago, including a laboratory course in physical chemistry with Dr. Emil Fischer, a later Nobel laureate.

In 1904, he was called to evaluate a medical student from Grenada who had a strange illness. He had a sore on his ankle and evidence of previous scarring. On evaluating a blood smear, Herrick found that his red blood cells were sickled. Over the next few years he evaluated the condition and published the landmark paper in 1910.2 Around the same time, in his evaluation of patients with heart attacks, he reviewed pathologic findings and began experiments on laboratory animals, ligating coronary arteries to evaluate their effects. In 1912 he published the description of the relationship between myocardial infarction and coronary thrombosis, entitled “Clinical Features of Sudden Obstruction of the Coronary Arteries.”

Although Herrick’s description of the clinical aspects of coronary thrombosis was the landmark paper, there were predecessors, as Herrick pointed out. The first case of coronary thrombosis described ante mortem was presented in 1878 by Adam Hammer,1,4 and the first completed description of the disease was published in 1910 by Obrastzow and Straschecko.1,5

Much of the paper is a description of previous experimental, pathologic, and clinical studies that demonstrated that sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries is not always fatal. Many of these studies originated from Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, up to within five years of the publishing of his paper. For example, he cites the work of Hirsch and Spalteholz in 1907 to indicate that the coronary anastomoses of the dog are patent, and similar anastomoses are present in humans.1,3,6

Before his paper, many believed that coronary occlusion led to sudden and inevitable death. His article examined the earlier studies that led to this prevailing view. Animal studies in which the coronary arteries were clamped or ligated had produced prompt fatality. Pathologists such as Cohnheim had concluded that the coronary arteries were end arteries and that occlusion of a coronary artery was associated with death within several minutes.

However, later work in experimental animals beginning in the late 1880’s demonstrated survival after coronary ligation. Herrick gave as an example the work of Porter where over half the animals lived after ligation of the anterior descending coronary artery.3 Herrick pointed out that the anesthetic given the animals during such experiments contributed to outcomes. He cited autopsy records that demonstrated anastomoses associated with large artery obstruction that were not the cause of death.

He presented two case studies in which he was involved to demonstrate the clinical findings of coronary occlusion.3 In only one was necropsy evaluation accomplished, by his friend and colleague Dr. Ludwig Hektoen, without whom my article and this symposium would not have been impossible. Herrick concluded on the bases of these and other studies that “there is no inherent reason why the stoppage of a large branch of a large branch of a coronary artery, or even the main trunk (left main), must of necessity cause sudden death.”3

He classified clinical associations with coronary occlusions into four categories: (1) symptomless sudden death; (2) “anginal” pain and shock with death following after several minutes; (3) severe but atypical symptoms that would not indicate cardiac disease but would occasionally lead to fatality; and (4) non-fatal cases with mild symptoms. Using an electrocardiogram, newly available for evaluation, Herrick described the symptoms and clinical pathological findings as congestive heart failure, shock, rupture associated with asystole, and cardiac rhythm disturbance after coronary occlusion, respectively. Although Herrick did not used the term “myocardial infarction” or “heart attack,” it was clear that this was the condition he was describing.

In addition, he recommended various interventions that in later times would be considered contraindicated. For example, he proposed routine use of digitalis preparations and avoidance of nitroglycerine because “digitalis . . . by increasing the force of the heart’s beat, would tend to help in that direction more than the nitrites.”3 He encouraged use of rapid intravenous preparations. Of course, nitrites are now given routinely as soon as acute coronary syndrome is suspected and intravenous or any other use of digitalis, which may produce life-threatening dysrhythmias, is discouraged except as a possible adjunct in treating atrial fibrillation. It is now the policy to rest the heart or decrease left ventricular wall stress under these circumstances by use of agents that slow the heart rate and decrease peripheral vascular resistance.

Herrick also advised absolute bed rest for several days. Before we criticize him for his recommendations, we should recognize that even decades later, in fact through the 1960s, the treatment of myocardial infarction included large doses of digitalis preparations and other inotropic drugs, the regular administration of anticoagulants, and bed rest for at least a week.

Nevertheless, Herrick came to some astute conclusions that have been confirmed subsequently. For example, in regard to the left anterior descending coronary artery, he stated that “the reputation of the descending branch of the left coronary artery as the artery of sudden death is not undeserved.” It should be of interest that it was as late as the early 1980s that angiographic and post mortem observations confirmed Herrick’s conclusions that sudden thrombotic obstruction of a coronary artery produces most myocardial infarctions. This is in comparison to the contrasting evidence that gradual stenosis leading even to complete occlusion may not cause infarction because of the gradual development of collateral anastomoses from patent coronary arteries to the vessel beyond the obstruction.

Despite the depth and importance of his 1912 paper, when Herrick presented the material before the Association of American Physicians, in his words, “It fell like a dud.”7 He continued to espouse his conclusions in what he termed “missionary work.”7 In a further report to the Association in 1918, including two additional cases with autopsies, he again presented his work and published papers on his experimental work with coronary ligations. 8,9

Beyond his initial contribution to the initial consequences of coronary occlusion, Herrick was an early advocate of the use of electrocardiography in diagnosis of this condition. He continued his teaching and practice and was a founder of the Chicago Heart Association. In fact, in 1922, the chair of the grievance committee of the Chicago Medical Association accused the new association of existing for financial gain at the expense of the family practitioner. Herrick successfully defended the group.7

Herrick was a strong advocate for family medicine, but recognized that there were differences in aptitude and scientific interest among physicians. In a paper in 1934 on the practitioner in the future, he summarized his strong feelings:

When analyzing the features involved in this problem and in order to reach conclusions that are sound, one has to give up some idealism, and, as a realist, to confess that not all physicians are born with equal ability. Some are by nature more capable of study, teaching, writing, or carrying on productive work at the bedside or in the laboratory.10,11

Herrick’s many achievements in later years included becoming president of the Association of American Physicians in 1923 (one year after he defended the Chicago Heart Association from attack), and receiving the Kober Medal in 1930 from the Association, its highest award, for his work on cardiovascular disease. The institution of the annual Herrick award by the American Heart Association was mentioned previously. He served as president of several organizations, including the Chicago Pathological Society, Chicago Society of Internal Medicine, American Heart Association, and the Chicago Chapter of the Society of Medical History. His area of interest clearly extended beyond cardiology to general medicine.

Herrick’s interests and writings also extended to the arts and literature. He had a great interest in Chaucer, having read all of Chaucer’s writings. He was a member of the Chicago Literary Club from 1909 until his death in 1954. His eleven essays presented to the Club included such topics as “Why I Read Chaucer at 60,” “William Lilly, a 17th Century Astrologer and Quack,” “Medical Diagnosis for the Layman,” “Castromediano, A Forgotten Patriot and Martyr of the Italian Risorgimento,” and “My Summers in the Garden.”12

As a faculty member at Rush since 1972, I am amused by the comment he made when, at age 78, in 1939, he delivered the principal address at the 50th anniversary of the opening of the Johns Hopkins Hospital:

There was a peculiar pleasure at realizing that they had selected as their speaker not some leader in medicine from the East but a physician from the West, who was, moreover, a graduate of Rush College which, in the opinion of the high-brow critics of the time, was unworthy of being rated as a first-class medical school.10,13

References

- Willius FA, Keys TF. Classics of Cardiology. Volume Two, pp. 815-830, Dover Publications, Inc New York 1961.

- Herrick JB. Peculiar elongated and sickle-shape of red blood corpuscles in a case of severe anemia. Archives Int Med 1910;6:517-521

- Herrick JB. Clinical features of sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries. JAMA 1912;59:2015-2020.

- Hammer A. Ein Fall von thrombotischem Verschlusse einer der Kranzarterie des Herzns. Am Krankenbette konstratirt. Wien med Wchnschr 1878;28: 97-102.

- Obtrastzow WP, Straschesko ND. Zur Kenntnis der Thrombose der Koronar arterien des Herzens. Ztschr f kiln Med 1910;71: 116-132.

- Hirsch and Spalteholz. Koronararterien und Herzmuskel. Deutsch. Med Wchnchr 1907, no. 20.

- Willerson JT. James B. Herrick memorial lecture. Circulation 1994;89: 1875-1881.

- Herrick JB. Thrombosis of the coronary arteries. JAMA 1919;72:387-390.

- Herrick JB, Smith FM. The ligation of coronary arteries with electrocardiographic study. Arch Intern Med 1918;22: 8-27.

- Ross RS. A parlous state of storm and stess. The life and times of James B. Herrick. Circulation 1983;67: 955-959.

- Herrick JB. The practitioner of the future. JAMA 1934;103: 1934.

- The Chicago Literary Club. One Hundred Twenty-Five years 1874-1999. Chicago:2001.

- Herrick JB. Memories of eighty years. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. P. 198.

PHILIP R. LIEBSON, MD, graduated from Columbia University and the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center. He received his cardiology training at Bellevue Hospital, New York and the New York Hospital Cornell Medical Center, where he also served as faculty for several years. A professor of medicine and preventive medicine, he has been on the faculty of Rush Medical College and Rush University Medical Center since 1972 and holds the McMullan-Eybel Chair of Excellence in Clinical Cardiology.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 5, Issue 2 – Spring 2013

Leave a Reply