Lloyd Klein

San Francisco, California, United States

The main cause of death during the American Civil War was not battle injury but disease. About two-thirds of the 620,000 deaths of Civil War soldiers were caused by disease, including 63% of Union fatalities. Only 19% of Union soldiers died on the battlefield and 12% later succumbed to their wounds. But thousands of soldiers and citizens alike died from typhoid, tuberculosis, mumps, measles, and dysentery. These communicable illnesses spread rapidly in both Union and Confederate Army camps because of crowding, poor hygiene, lack of sanitary disposal of garbage and human waste, and inadequate nutrition. In addition, mosquito-borne illnesses such as malaria and yellow fever caused acute and chronic disease. Amputations were associated with a high rate of post-operative infections, leading to disability and death. Today, antibiotics, sterile surgical technique, and publicly funded mosquito eradication are hallmarks of modern medical and public health systems.

Infectious disease: The problem of diagnosis

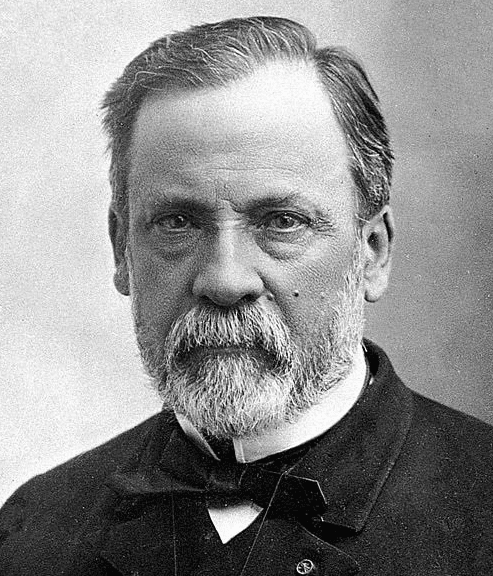

At the time of the Civil War, Louis Pasteur in France and Joseph Lister in Britain were just beginning to study the possibility that some diseases were caused by microorganisms. Although the concepts of epidemics and communicable illness were recognized, no one understood what caused them or the need for sterility in preventing them. The germ theory of disease and practice of sterile wound care did not develop widely for another ten to twenty years.

Obviously, this created serious problems during the war, but it also poses a problem for the historical analysis of disease. Blood, urine and sputum cultures did not exist, nor the many other laboratory tests we now take for granted. For example, nineteenth-century physicians categorized malaria according to how often fever spikes or “paroxysms” occurred. A “quotidian” fever recurred every twenty-four hours, a “tertian” every forty-eight, and a “quartan” every seventy-two. P. vivax malaria was commonly referred to as “intermittent fever” or “ague,” while malaria caused by P. falciparum was known as “congestive fever,” “malignant fever,’” or “pernicious malaria” because of its potentially lethal result.

Common Illnesses

It is estimated that half of all deaths in the Civil War were from dysentery or malaria. Both conditions occurred in the same kinds of environment. Shigella, Salmonella (typhoid), and E. histolytica, often as food-borne contaminants, caused many cases of diarrhea and dysentery. However, malaria is also associated with intestinal illness in 5–38% of cases, most often presenting as chronic diarrhea. The syndrome can be clinically identical to bacillary dysentery. It is a slow, wasting disease and was almost incurable during the Civil War.

Crowded living conditions introduced new germs and diseases to men of disparate backgrounds. This lack of natural immunity led to epidemics of measles, chickenpox, pertussis, and other so-called “childhood” illnesses, which could be lethal. Pneumonia was also a significant cause of death.

Malaria and yellow fever, both mosquito-borne illnesses, were pervasive in the western theater, where hot weather and standing water were believed to cause vapors (“mal air”) to arise from rotting vegetation. The organisms responsible for these diseases and their mosquito vectors were not fully established until decades after the war.

Although quinine as a cure and a preventative measure for malaria was well known, having soldiers take the bitter liquid was difficult. Often it was mixed with rum or whiskey. Quinine was plentiful in the North because of a government-funded business to produce it, but it was scarce in the South. Attempts to find an alternative in the South proved fruitless.

Sanitation

At the beginning of the war, the wounded and ill were treated in unsanitary and crowded conditions. The need for strict sanitation became apparent as the war continued. Requirements to drink only pure water, to keep latrines away from campsites, and not to eat spoiled food were poorly understood before the war. Consequently, dysentery, yellow fever, smallpox, and typhoid, among others, ran rampant in camps. The United States Sanitary Commission was created early in the war to raise money for medical supplies for the Union Army and to provide hygienic advice to Union Army soldiers.

Because of the efforts of Jonathan Letterman, the Surgeon General of the Union Army, hospital care was improved. He designed well ventilated hospital wards, which helped to limit the spread of disease. He also developed standard procedures and requirements for hygiene and hospital care, including an inspection plan to ensure these standards were met. The exceptional leadership of women in the Sanitary Commission was also key, and included Clara Barton, Dorothea Dix, and “Mother” Bickerdyke.

Surgical treatment of battle wounds

Battle descriptions in the memoirs of those who were there never fail to mention the cries of anguish of the wounded. The wounds produced by artillery, large bore bullets, and Minié balls were ghastly. Civil War battle casualties generally included 20% dead and 80% wounded, which created a huge problem for managing many wounded soldiers. About one out of seven died from his wounds, often from infection rather than blood loss.

Bone fractures from large bore armaments were defined as “compound” and bones broken into many fragments were called “comminuted,” both of which are terms that are still used today. These types of fractures provide perfect breeding grounds for bacteria and bone infections, called osteomyelitis, and would inevitably cause death if limbs were not amputated. The prolonged use of antibiotics is the modern treatment, which Civil War surgeons did not have.

Amputation

Amputations were the most common surgical procedure of the Civil War. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (MSHWR) reported the treatment of 174,000 shot wounds of the extremities. In these cases, 4,656 were treated by surgical excision and 29,980 by amputation, with a 26.3% mortality rate overall.

Although a gruesome procedure, amputation actually saved the lives of thousands who, had an infection from the wound been allowed to spread, would have died. Civil War surgeons did the right thing under the circumstances. Later scientific studies showed that wounded soldiers treated by Union or Confederate surgeons had lower mortality in all situations, including amputations, than did the British and French in the Crimean War.

Badly torn tissues where bullets or shells injured the body almost always became infected. The metal would break through the skin, carrying unsterile material into the fracture. Erysipelas, a streptococcal infection, caused many deaths, as did staphylococcal infections. Tetanus was a less common cause of infection but had a high mortality rate.

Civil War surgeons were derisively called “sawbones” because of the many amputations they performed. They were often inadequately trained and in many cases not qualified. Medical education in those times included only a two-year curriculum, with surgeons receiving an optional year of hands-on experience. Many military surgeons worked bravely and did the best job they could, often working dangerously close to the front lines. After the first year, Union surgeons decided that only the most technically expert would continue to operate.

Sterile technique during surgery had not become standard. Joseph Lister was its only proponent, and his advice was not initially heeded. Surgical cleanliness was a mere afterthought. Surgeons used the same instruments on patient after patient, never cleaning them. They wiped them off on an apron or in a bucket of water contaminated with the blood of many patients; there was no such thing as a sterilization process. Routine hand washing between cases and surgical gowns, drapes, and gloves had not yet been invented.

Gangrene

Gangrene as a consequence of surgical wound infections caused many deaths and prolonged recovery for months, even years. Many treatments were tried, including whiskey, cathartics, balanced diets, and topical agents including poultices of mud, flaxseed, slippery elm, or charcoal. Attempts with chlorinated soda water, extremely strong sodium hypochlorite solutions, nitric acid, tinctures of iodine and iron, and turpentine were applied. These are highly toxic substances. Not only did they not cure the infection, but they caused even more damage to healthy tissue. The use of maggots to clear dead tissue from wounds was initiated by a Confederate surgeon and remains an area of research today. Dr. Middleton Goldsmith was a surgeon in the Union Army during the Civil War who worked in Louisville, Kentucky. After treating many soldiers with gangrene, he made a brilliant observation. Goldsmith noticed that patients with gangrene recovered more often in wards where aerosolized bromine was used. He therefore placed volatile bromine in all patient wards, with surprising success. Buoyed by this experience, he developed a method of applying bromine deep into muscular layers after wound debridement. This involved injecting bromine subcutaneously once and then applying it topically to exposed surfaces. In an era when the mortality rate for hospitalized patients with gangrene was 45%, Goldsmith’s method, tested in over 330 cases, yielded a mortality rate of less than 3%. The report included data, photographs, and case reports. Goldsmith’s revolutionary bromine therapy is not as well recognized as the work of Pasteur and Lister, but his contributions were made earlier. Bromine is still frequently used as an antiseptic in modern medicine.

Which campaigns were most affected by disease?

Chickahominy Fever, an illness prevalent in 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign, is now thought to have been a combination of malaria and typhoid. Malaria was a serious problem in the Vicksburg campaigns of 1862 and 1863. Salmonella was rampant in the western theater in 1864. And typhoid fever resulted in many deaths, especially among officers, likely related to contaminated food during long campaigns in the field.

Conclusion

Events of the Civil War cannot be simplified to merely battlefield movements or strategic planning. Acknowledging the roles of communicable food- and insect-borne illnesses, their differential effects on the two armies, and the diverse ways the two governments reacted to their existence, enhances our understanding of the Civil War.

Further reading

- Alfred Jay Bollet, A. M. Bell, “Trans-Mississippi Miasmas: Malaria & Yellow Fellow Fever Shaped the Course of the Civil War in the Confederacy’s Western Theater,” East Texas Historical Journal 47 (2009).

- A.J. Bollet. The major infectious epidemic diseases of civil war soldiers. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2004; 18: 298.

- J.S. Sartin. Infectious diseases during the Civil War: the triumph of the “Third Army.” Clin Infect Dis 1993; 16:580.

- Bell AM. Trans-Mississippi Miasmas: Malaria & Trans-Mississippi Miasmas: Malaria & Yellow Fellow Fever Shaped the Course of the Civil War in the Confederacy’s Western Theater. East Texas Historical Journal 2009; 47:3–13.

- Miller GL. Historical Natural History: Insects and the Civil War. American Entomologist 1997; 43:227-245.

- Brown M. The American Civil War as a biological phenomenon: did Salmonella or Sherman win the war for the North? https://hekint.org/2017/01/22/the-american-civil-war-as-a-biological-phenomenon-did-salmonella-or-sherman-win-the-war-for-the-north/

- Gilchrist MR. Disease and Infection in the American Civil War. The American Biology Teacher. 1998;60(4):258–261.

DR. LLOYD W. KLEIN, MD, is Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. He is a nationally recognized cardiologist with over thirty-five years’ experience and expertise. He is also an amateur historian who has read extensively and published previously on the Civil War, with a particular interest in political and military leadership and their economic ramifications.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 3 – Summer 2022

Leave a Reply