Brody Fogleman

Harsh Jha

Noel Brownlee

JuliSu DiMucci-Ward

Spartanburg, South Carolina, United States

|

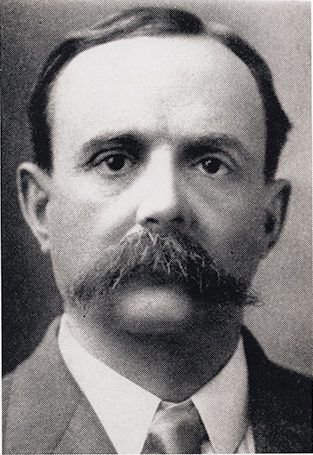

| James Woods Babcock (1856–1922). Photo courtesy of the Waring Historical Library, MUSC, Charleston, SC. |

Pellagra is a disease of vitamin B3 (niacin) deficiency. Niacin is the precursor for many physiologic processes involving nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), an enzyme that carries out long biochemical processes essential to a wide range of metabolic functions. While the understanding of niacin physiology is relatively new, the disease of pellagra is an ancient one, found wherever poverty-stricken populations and grain-based diets exist. Pellagra is classically described through the “four D’s,” which include diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death.1 Appreciating that dementia is a key manifestation of pellagra is crucial in understanding why a South Carolina insane asylum’s superintendent became a key figure in the American history of pellagra.

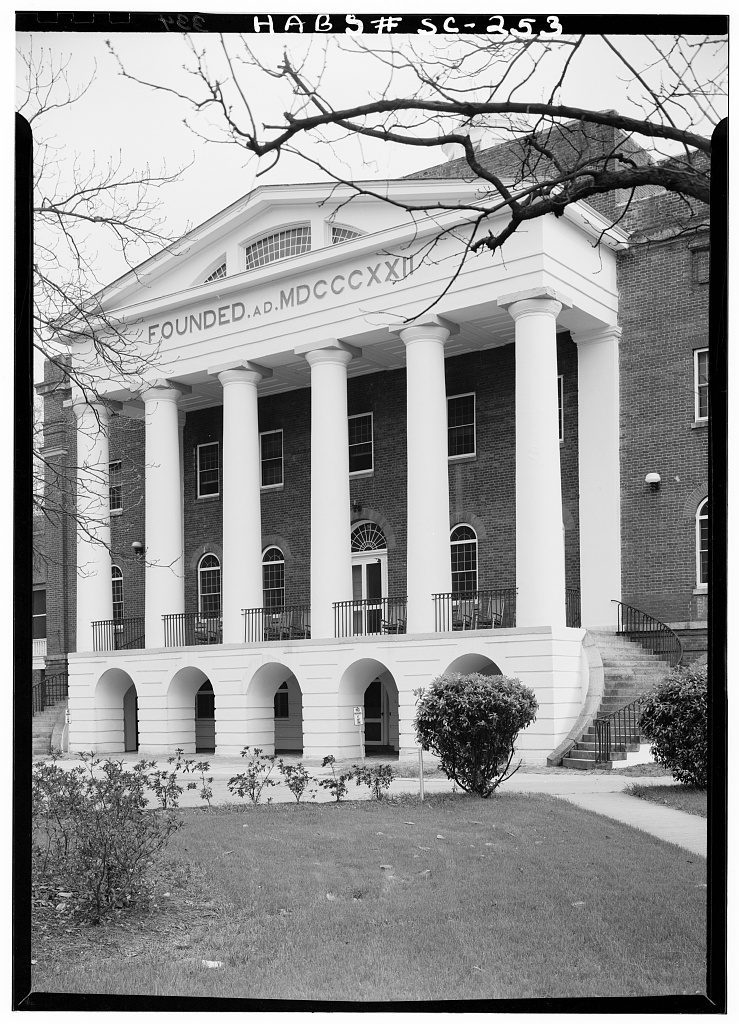

James Woods Babcock (1856–1922) was an American psychiatrist tasked with overseeing the state of South Carolina’s sole institution for the mentally ill—the South Carolina Insane Asylum in Columbia, South Carolina.2 He was the superintendent at that facility from 1891 to 1914, the notable bulk of his career. Dr. Babcock was best known for being one of many to describe the disease of pellagra, known now as niacin deficiency. He found himself in a situation similar to many modern physicians: trained as a scientist but practicing in the unfamiliar rapids of politics and business.2

Dr. Babcock’s tenure at the South Carolina Insane Asylum is well documented in the book Asylum Doctor by Charles S. Bryan.2 While not the first to diagnose pellagra in the US, Dr. Babcock traveled to Italy and independently verified in 1908 that the disease he had observed in his work was the same pellagra that was well known in Italy. This formal recognition that pellagra did exist in the US led to a dramatic rise in the number of pellagra cases being properly identified by physicians in the early 1900s.3

In his book about Dr. Babcock, Dr. Charles S. Bryan captures the dual perspective through which Babcock is judged: as a capable physician making strides in diagnosis and treatment, and as an incapable administrator who failed to produce demonstrable results.2 The divergent views surrounding Babcock’s contributions, or lack thereof, to solving pellagra is evident when examining historical literature. In a letter by Dr. F.M. Sandwith in Transactions of The National Association for The Study of Pellagra, Babcock and others were described as “prominent pioneers in awakening the interest of the medical profession in the United States to the importance of [pellagra].”4 It is claimed in Asylum Doctor that he did not have the necessary resources to fully support the National Association for Study of Pellagra in the first place. This is the groundwork for the claims of Babcock’s failures.5

Dr. Babcock, among others, was a prominent pioneer at the first pellagra conference in 1908 and was thanked for his “enthusiasm and energy in initiating and carrying to a successful conclusion the present meeting [conference].”6 The conference proceedings were reminiscent of modern scientific discourse, as various opinions clashed and dulled each other’s momentum. At the time, the prevailing medical opinion was influenced by the recently discovered germ theory, which suggested that pellagra was an infectious disease transmitted by a biting insect.7 Babcock’s opinion that pellagra was a disease caused by an impoverished diet was unpopular—accepting this hypothesis would have been an indictment on Southern ways of life.7 In Transactions of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, Babcock writes of the political will to suppress case reports of pellagra as a disease affecting Americans.8 He notes that he “demonstrated a case of pellagra to the asylum officer in charge, but was not asked to extend my observations, and I know that the presence of pellagra there was subsequently denied.”8 The misconception of his theory as an attack on Southern culture was further enhanced by the fact that many other diseases common in this region were the result of infectious agents such as hookworm.9

|

| The State Lunatic Asylum of South Carolina located in Columbia, South Carolina. Photo via Historic American Buildings Survey, SC-253. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. No known restrictions on publication. |

The pellagra conferences in South Carolina, of which Babcock was recognized as a prominent leader, marked a critical turning point in the history of medicine and scientific advancement. Dr. Rupert Blue described the issue of pellagra in the South as a “national danger.”10,11 He contended that a solution for pellagra would require the cooperation of the US federal government, states, and most importantly, the general public. Just as today, the people drive common interest and elect officials to influence the goals of the majority—a component, as described by Dr. Blue, that was essential to urging lawmakers to obtain federal aid.10,11

The modern reader will appreciate the parallels between Babcock’s struggle and those faced by current scientists. Scientific research will have a hard time gaining traction if going against the dominant trends of politics and dogma. Similarly, this situation justifies Babcock’s limited success during his tenure at the South Carolina asylum—his every request for proper funding was ignored by a Senate unwilling to acknowledge that Southern austerity could have negative impacts on constituents.

The devastating outcomes of the pellagra epidemic in Southern US states can be attributed to poverty. It was later recognized that the root issue was malnutrition, a result of a monotonous diet. This was most likely a ramification of the introduction of the Beall degerminator, a machine used to process corn that inadvertently removed major nutrients like niacin. This caused political frustration in the South and exacerbated economic struggles as the cause of pellagra became more thoroughly understood.12

A century later, the fortification of affordable foods with niacin has led to pellagra now being a symptom of particular kidney, liver, and oncologic pathologies, rather than an explicit disease of an impoverished diet. The cultural mythos of poverty still depicts the poor as wasting and underweight, while the reality is that affordable foods for the poor are deficient in nutrients, not calories. Tamargo et al. notes the current implications of food insecurity, making the generalization that the association between higher body mass index (BMI) and development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is stronger in food-insecure individuals than for those with adequate access to food.13

While B3 fortification of modern foods has nearly eradicated pellagra in the US, niacin remains relevant for modern epidemiologic efforts. Linder et al. notes that niacin decreases hepatic lipogenesis and is synergistic with other dietary lifestyle modifications, finding in a study of 202 subjects that “high baseline niacin intake predicted a larger decrease of liver fat.”14 A potential explanation may be that niacin inhibits DGAT2, a protein that performs the final step in liver fat production.14 This highlights the argument that while the historical perspective of pellagra may be easily neglected in modern medicine, it is crucial for clinicians to have an understanding of the history of diseases like pellagra. Just as the discovery of pellagra as a disease required an understanding of the historical and social context in which it occurred, appreciating the history of diseases today can provide valuable insights into their current and future impacts. Even though the disease may not be clinically apparent, the consequences of its deceptive silence may have wide-ranging effects that are yet to be fully elucidated.

James Babcock’s fight against pellagra can best be summarized as successful in the broader sense, with modest success at his own facility. Because of a lack of funding and political initiative, conditions at his own facility did not substantially improve during his tenure. In the broader scheme of things, his 1908 confirmation of American Pellagra as the same disease widely recognized in Europe paved the way for a rising recognition of endemic pellagra cases in the Southern US. Furthermore, his spearheading of the conferences of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra brought the disease to a renewed national and global consciousness, establishing the groundwork for the eventual discovery of pellagra’s underlying etiology. Babcock’s successes and failures offer a valuable lesson to contemporary scientists and physicians, highlighting the need to understand the historical context of disease recognition, etiologic discovery, and medical advancements within a persistently evolving political and economic landscape.

References

- Beardsley, Ed. “Pellagra.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies. Accessed Dec 12, 2022. https://scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/pellagra/.

- Bryan, C. Asylum Doctor: James Woods Babcock and the Red Plague of Pellagra. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 2014.

- Transactions of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra. Columbia, SC: RL Bryan; 1914. p. 17.

- Transactions of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, p. 97.

- Bryan, Asylum Doctor, p. 247.

- Lavinder, CH. The National Conference on Pellagra, Held at Columbia. Sage Publications, Inc. p. 1702. https://jstor.org/stable/pdf/4564077.pdf.

- Bryan, Asylum Doctor, pp. 96-105.

- Transactions of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, p. 17.

- Bollet, Alfred J. “Politics and pellagra: the epidemic of pellagra in the US in the early twentieth century.” The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 65, no. 3 (1992): p. 211.

- Transactions of the National Association for the Study of Pellagra, p. 3-4.

- Bryan, Asylum Doctor, p. 228.

- Bollet, “Politics and pellagra,” pp 211-21.

- Tamargo, JA et al. “Food insecurity is associated with magnetic resonance–determined nonalcoholic fatty liver and liver fibrosis in low-income, middle-aged adults with and without HIV.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2021;113(3):593-601. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa362.

- Linder, K et al. “Dietary niacin intake predicts the decrease of liver fat content during a lifestyle intervention.” Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-38002-7.

BRODY M. FOGLEMAN earned his BS in Biomedical Engineering from North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill in 2021. He is currently a second-year medical student pursuing his Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree at Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, with an expected graduation date of 2025. Brody is passionate about medical humanities, global health, and exploring the role of social factors that influence health outcomes. He plans to pursue a residency in internal medicine and specialize in gastroenterology.

HARSH JHA is a University of Florida alum and current third-year medical student pursuing his Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree at Edward Via College, with plans to graduate in 2024. He is notably interested in the history of medicine, representation of disease in historic art, as well as modern topics such as general surgery, nutritional medicine, and exercise physiology. Harsh’s non-medical interests include home cooking, amateur farming, and short distance running.

DR. NOEL BROWNLEE completed his undergraduate education at Wofford College, his PhD in cancer biology at the Medical University of South Carolina, and his MD at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine followed by graduate anatomy and clinical pathology studies at Duke, Wake Forest, and Johns Hopkins University Hospitals. He is currently professor and chair of pathology at the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine and has a longstanding interest in the history of medicine and South Carolina.

DR. JULISU DIMUCCI-WARD, Assistant Professor for Prevention and Public Health at Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine, has expertise in human nutrition and healthcare genetics. With experience as a clinical dietitian and diabetes educator in various settings, she, with her team, discovers and implements prevention and treatment strategies for individuals at risk of disease or injury. Dr. DiMucci-Ward aims to mentor medical students to become champions for prevention and public health.

Winter 2023 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply