Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“[W]e can seize the opportunity to honor the too-often-neglected accomplishments of [B]lack Americans in every endeavor throughout our history.”1

– President Gerald Ford, 1976

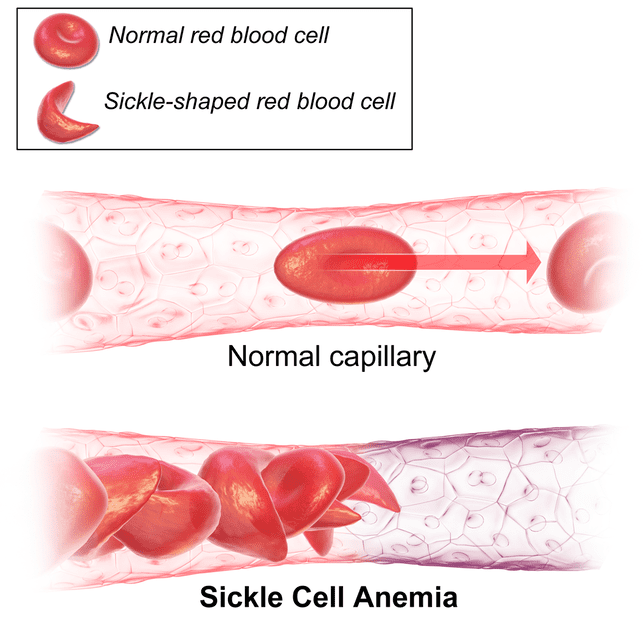

Sickle cell anemia. Illustration by BruceBlaus on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Marilyn Gaston, MD (b. 1939), grew up in a poor family, with both parents working at low-wage jobs. She graduated from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in 1964, one of six women in her graduating class, and the only Black person. During her pediatric residency, she decided to learn as much as possible about sickle cell anemia. In 1972, she became the director of the Sickle Cell Center in Cincinnati. She left that position in 1976 when she was invited to join the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.2,3

Sickle cell anemia, or sickle cell disease, is a condition caused by the presence of two genes that both produce an abnormal form of hemoglobin, hemoglobin S. Red blood cells containing only this abnormal hemoglobin will deform and change shape under certain stressful conditions such as dehydration or fever. They no longer pass easily through capillaries and cause “crises” of vaso-occlusion, resulting in pain, tissue death, or strokes. Splenic infarctions result in an increased susceptibility to certain bacterial infections.

One in 365 Black children in the US is born with sickle cell disease. Today, ninety percent of people with sickle cell disease survive to age twenty; fifty percent survive beyond age fifty.4 New York State began newborn screening for sickle cell disease in 1975.5 The Netherlands began a voluntary screening program in 1974 and nearly all newborns were tested. Spain began a similar program in 1978, and the French West Indies in 1983.6 If a child tested positive, however, there was nothing that could be done other than monitoring for signs of infection or vaso-occlusive crises.

This feeling of hopelessness diminished greatly with the publication of an article by Gaston and colleagues in 1986: “Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell anemia.”7 In this study, due to their susceptibility to bacterial infections, children younger than three years of age were randomized to receive either 125 mg of penicillin-V potassium twice a day or placebo. The study was stopped eight months earlier than originally planned because there was an 84% percent reduction in the incidence of infection in the penicillin group. No deaths from pneumococcal septicemia occurred in the penicillin group, but three occurred in the placebo group. The article recommended that newborns be screened for sickle cell disease, and, if positive, they should start receiving oral penicillin prophylaxis by four months of age.

Within a year of the article’s publication, forty states started screening programs.8,9 Wisconsin began in 1988,10 Missouri in 1989.11 Abroad, France began screening in 1995, the UK in 2002, and the Canadian province of Ontario in 2006.12 As of 2019, Germany and Italy do not yet have sickle cell disease as a target disease in their newborn screening.13

In 1990, Dr. Gaston became the director of the Bureau of Primary Health Care of the US Health Resources and Service Administration. The mission of this agency is to increase poor Americans’ access to health care, and this has been the cornerstone of Dr. Gaston’s efforts. She was also appointed Assistant Surgeon General of the United States that same year.

Since her “retirement” in 2001, she has concentrated on “promoting the importance of prevention as a health care strategy.”14

References

- Ford, Gerald. “Message on the Observance of Black History Month,” Feb 10, 1976. Selected Speeches, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library & Museum, Feb 1, 2002. https://fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/speeches/760074.htm.

- “Marilyn Gaston.” Wikipedia.

- “Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD,” Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), Maryland State Archives. msa.maryland.gov/msa/speccol/sc3500/sc3520/014500/014533/html/msa14533.html.

- “Sickle cell disease.” Wikipedia.

- Cynthia Minkovitz et al. “Newborn screening programs and sickle cell disease,” Am J Prev Med 51(1 suppl 1), 2016.

- Yvonne Daniel et al. “Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in Europe,” Int J of Neonatal Screening Feb 12;5(1), 2019.

- Marilyn Gaston et al. “Prophylaxis with oral penicillin in children with sickle cell disease,” NEJM 314(25), 1986.

- “Marilyn Gaston, MD, sickle cell disease pioneer and public health advocate,” Sickle Cell Medicine and Humanities Project. sicklecellmedicineandhumanitiesproject.wordpress.com/3-2/.

- “Update: Newborn screening for sickle cell disease – California, Illinois, and New York, 1998,” Centers for Disease Control Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 49(32), 2000. https://cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4932a1.htm.

- “Sickle Cell Trait” Tri-Fold Brochure P44566, Wisconsin Department of Health Services, 2014. https://dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p4/p44566.pdf.

- “Timeline of Newborn Screening.” Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. https://health.mo.gov/living/families/genetics/newbornscreening/toolkit/pdf/timeline.pdf.

- “The history of sickle cell: 2006 – Newborn screening for sickle cell begins in Ontario,” Sickle Cell Association of Ontario. sicklecellontario.ca/about-sickle-cell/the-history-of-sickle-cell/.

- Daniel et al, “Newborn screening.”

- Maryland State Archives, “Marilyn Hughes Gaston.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Leave a Reply