JMS Pearce

Hull, England

Medicine has bred many odd but audacious characters, eccentrics, polymaths and “truants.” One might argue that those characteristics attracted such people to careers in medicine: a chicken and egg dilemma. Conversely, some have argued that modern regulated uniformity has infected medicine and stultified originality.

A little-known medical eccentric and heretic was John Walker MD (1759–1830), primarily a vaccinator and writer. Like Wordsworth, he was born at Cockermouth and educated at its free grammar school. In the same town lived the Quaker William Woodville MD FLS, a botanist who from 1791 was physician to the Smallpox and Inoculation Hospitals at St. Pancras in London.1

Walker spent five years in his father’s ironmonger business, engraving ornamental metalwork. He also studied drawing. In 1779 he renewed his artistic work and within a year was publishing engravings in magazines.

His second career began in 1784 near Dublin, where he started a large and successful school, teaching classics and mathematics. However, he continued to produce engravings and educational texts to supplement his meager income. He published Elements of Geography and of Natural and Civil History in 1788 and a Universal Gazetteer Being a concise description, alphabetically arranged, of the nations, kingdoms, states… in the known world in 1795.2

The ebullient, radical Walker moved to London and again changed his career. He undertook a conventional course in medicine at Guy’s Hospital, graduating MD from Leiden University in 1799. He later published his thesis on the function of the heart and blood vessels. He became a licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians London in 1812. Anne Bowman, a native of Cockermouth, had financed his medical studies. They married but were childless.

If Walker’s medical education was conventional, his career was not. After art, engraving, writing, and teaching he visited Paris and there met the leading politicians of the French Revolution. We can see his unconventional idealism when he became secretary to the Theophilanthropist Society, of which Thomas Paine was a prominent member. Theophilanthropism was a form of deism, whose adherents like Voltaire believed in the existence of a God of reason, fraternity, and humanity. By 1802 it was deemed unlawful.

Walker rarely practiced medicine. His work was confined to vaccination. This unusual career path was in step with his quarrelsome, eccentric character, and his skepticism about orthodox medical treatment, religion, and politics. Nonetheless, he was a man seeking spiritual virtues1 who embraced pacifism and radical causes that opposed slavery, employment of children as chimney sweeps, and cruelty to animals. Though raised as a Baptist, he considered himself a Quaker but tried unsuccessfully to join the Quaker Society of Friends. Despite their rejection, he followed their outward conventions, including their drab clothes. And he defied social etiquette by his refusal to remove his hat at dinner.

Jennerian vaccination

Variolation—inoculating skin with fresh smallpox lesions3—was brought to Europe from Asia in the eighteenth century with a mortality rate of around two to three percent. It was replaced by vaccination when in May 1796 Edward Jenner (1749–1823) bravely inoculated cowpox matter from Sarah Nelms, a dairymaid, into his gardener’s eight-year-old son James Phipps, resulting in only a mild illness. In July, Jenner again inoculated the boy with matter from a fresh smallpox lesion. No disease developed. Smallpox vaccination was born. Variolation was banned by Act of Parliament in 1840 and vaccination with cowpox was made compulsory in 1853. After successful freeze-dried modifications, in May 1980 the WHO announced that smallpox had been eradicated worldwide.

With his friend Dr. Marshall, John Walker, at the request of the Neapolitan government, took “vaccine lymph” to Naples, Malta, and Gibraltar. On his return, he accompanied the army to Egypt, where he administered Jenner’s vaccine to thousands of troops.

Back in London in 1802, he immediately began to practice vaccination. With a handsome salary he was appointed secretary and resident vaccinator to the Royal Jennerian Society at its headquarters in Salisbury Square—a charity set up by Jenner with the eminent Quaker physician John Coakley Lettsom MD FRS (1744–1815). However, Walker’s behavior and techniques were far from impeccable; he and the usually placid Jenner fell into conflict,1,5 which caused serious and prolonged disputes with Jenner’s Society, culminating in Walker’s forced resignation in 1806 (Fig 1).

Jenner’s procedure was at first frequently and vehemently attacked as injurious and sometimes ineffective,4 although thousands of Londoners were successfully vaccinated. Its opponents included many senior physicians. Enthusiasm for vaccination abated, subscriptions declined, and alleged cases of smallpox after vaccination were publicized. The days of the Royal Jennerian Society soon ended. Shortly afterwards, the dedicated Walker continued to vaccinate for the National Vaccine Institute, which became the most successful vaccination charity of its day, and it was Walker who revived the flagging Jennerian Society in 1813. He vaccinated six days in every week, at six or more stations of the society.5

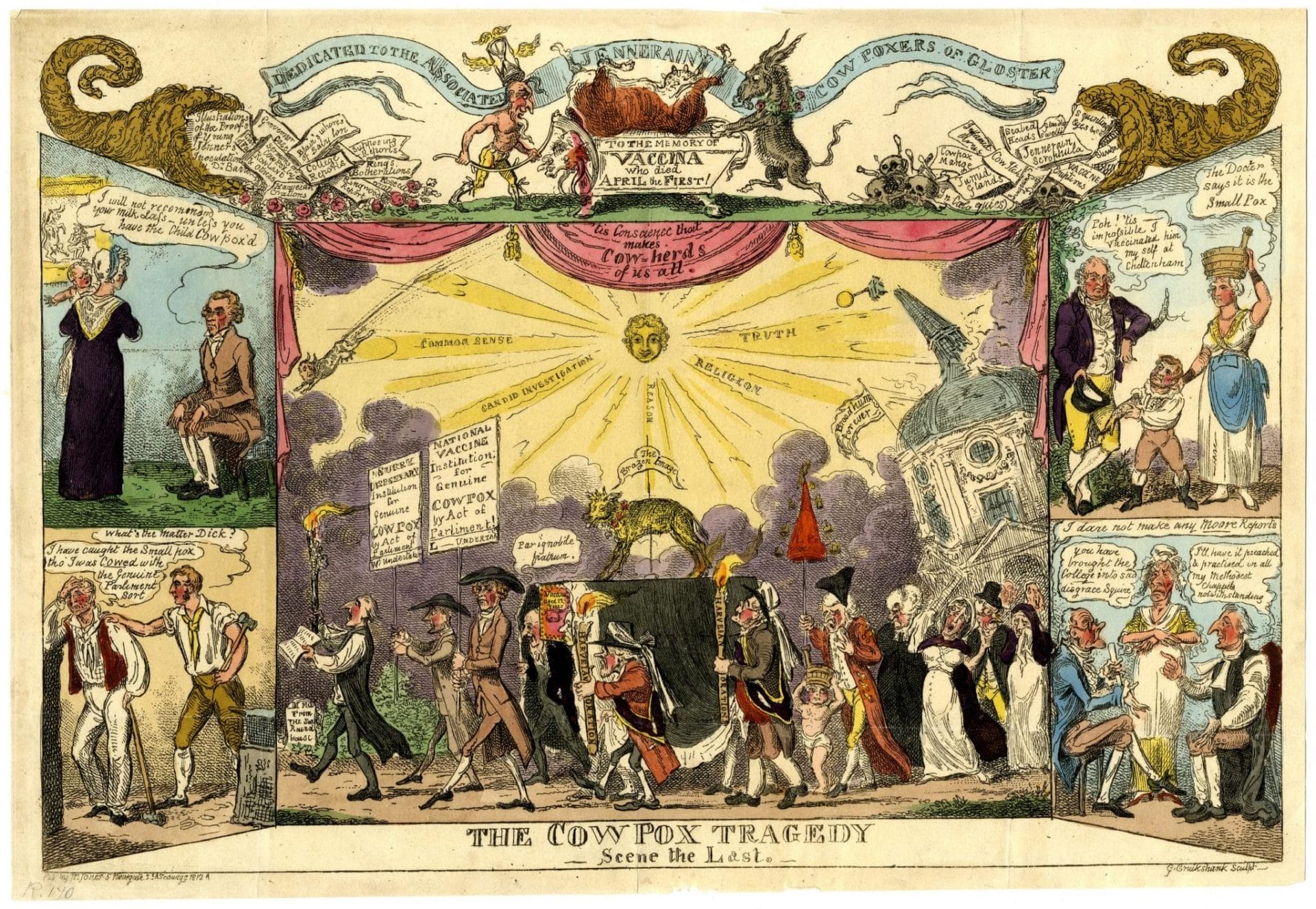

In the British Museum collection is an intriguing satirical cartoon of 1812 by the foremost British illustrator and caricaturist George Cruikshank: The Cow pox tragedy- scene the last– (Fig 2). The British Museum’s account describes:

“A large central design flanked by four small designs arranged… as in a plate published in 1803 by the Royal Jennerian Society, called ‘A comparative View of the Effects on Individuals and Society between the Small-pox and Cow-pox’. The main design is a funeral procession (right to left), the coffin inscribed ‘Vaccinia aged 12 Years’. Two bearers are seen under the pall; one points to two men heading the procession holding up placards; he says: ‘Par ignobile fratrum.’ Like Walker, the men are plainly dressed and Quaker-like. The placards read: ‘National Vaccine Institution for Genuine Cow Pox by Act of Parliament… L– Undertaker’ and ‘Surry Dispensary Institution for Genuine Cow Pox by Act of Parliament. . . W [? John Walker] Undertaker’.”

Despite its early vagaries, Benjamin Waterhouse performed the first vaccinations in Boston in July 1800 using material provided by Jenner. President Thomas Jefferson quickly promoted its use.

John Walker died in London on 23 June 1830, possibly from pleurisy of uncertain cause. Ever the medical skeptic, he refused medication. His biographer John Epps portrayed him:

Such was this extraordinary man. He knew human nature well. He did not seem to take any notice, but was always noticing. He scorned being influenced by trifles. The laugh of ignorance he did not regard; and the finger of contempt he did not observe. He felt pleasure in his own ways; and no displeasure of others could alter him.1

And, Munk’s Roll comments:

Whatever were Dr. Walker’s peculiarities and failings, and that they were many is admitted by his eulogist and biographer, Dr. Epps1 he deserves the greatest praise for his untiring efforts in behalf of vaccination, of which he was the apostle in this metropolis for more than a quarter of a century. During the whole of that period he vaccinated six days in every week, at six or more stations of the society, and was accustomed to boast towards the end of his life, that he had vaccinated altogether more than one hundred thousand persons.”5

The eccentricities of both Jenner’s and particularly John Walker’s practices might prompt us to consider that in modern times, much ultra-structured uniformity dominates medicine, led by those of lesser gifts of mind who have sought and often achieved undeserved prominence. By devising rules and creating arbitrary committee-based classifications and criteria, they obscure the natural variation of biological behavior and inhibit innovative research. The result is often a formalized but wholly artificial structured order, a uniformity that tends to suppress or conceal the sometimes quirky quests and unconventional searches for scientific truth.

References

- Epps John. The Life of John Walker, M.D. 8vo. London. 1831. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=9HOKF91dJF4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA3&dq=John+Walker+MD+&ots=R4-FKTqIkW&sig=a8TLzF_yPbKXfHrdPtxxCtsw7NI#v=onepage&q=John%20Walker%20MD&f=false.

- Brunton D. John Walker. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. http://oxforddnb.com/viewbydoi/10.1093/ref:odnb/28500.

- Pearce JMS. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Smallpox. Hektoen International Summer 2020.

- White William. The Story of a Great Delusion in a Series of matter-of-fact Chapters. London: E. W. Allen, 1885.

- Munk William. John Walker. Inspiring Physicians, also known as Munk’s Roll. (1759–1830). Vol III, Pg. 106.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.