Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“And my ‘medicine’ was the thing that gained me entrance to…[the] secret garden of the self…I was permitted by my medical badge to follow the poor, defeated body onto those gulfs and grottos[sic].”1

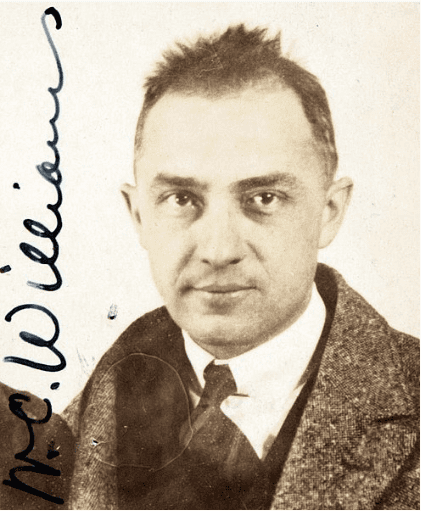

— William Carlos Williams, M.D.

William Carlos Williams (1883 – 1963), poet and physician, was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, the elder of two sons of Englishman William George Williams and Raquel Hélène Rose Hobeb, a Puerto Rican of French, Dutch, Spanish, and Jewish heritage.2 He was admitted to the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1902 after studying at an academically superior high school. In 1906 he began two years of residency at two hospitals in New York City, with concentration in obstetrics and pediatrics. Then he augmented his pediatric knowledge by studying in Leipzig.

Williams started general medical practice in 1909 in the town of his birth and remained in practice, always in Rutherford, for forty years. He began writing while in medical school and continued until near the end of his life. He wrote four novels, five plays, fifty short stories, and about 600 poems.3 His poetry is considered to be in the same category as Whitman, Longfellow, Sandburg, and Frost.4

In 1950, Williams received the National Book Award for Paterson, a book-length poem. He was chosen in 1952 to be the new Consultant to the Library of Congress, a position that later became Poet Laureate of the United States. He had a stroke that year and delayed accepting the position.

Soon after the end of World War II, the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics began a “cold war” of competing for global supremacy. The American government was worried about the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, the Berlin blockade (1948 – 1949), the communist victory in the Chinese Civil War (1949), the testing of an atomic bomb by the USSR (1949), and the joint Chinese-North Korean invasion of the American ally South Korea (1950). These events, combined with American xenophobia and attitudes towards communism, led to a “Red Scare” (1947 – 1957), a fear that domestic or foreign communists were infiltrating or subverting the American society and its federal government.5

The response of the federal government was to investigate. The US House of Representatives created the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The committee heard testimony from former American members of the Communist Party and from former Soviet spies, which confirmed that acts of espionage were going on. At the same time, Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin, chair of the Government Operations Committee in the US Senate, required many people to testify about their loyalty to the US and their sympathy for left-wing causes.6 Hundreds of academics, labor union leaders, and people in the entertainment industry were accused and smeared by innuendo. Many lost their jobs and became unemployable because of a “blacklist” that prohibited hiring listed people.

The House and McCarthy Committees used the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (the domestic intelligence and security service of the US and its principal law enforcement agency7) to investigate suspected individuals. Because Williams had been appointed consultant to the Library of Congress, he had to be investigated to determine his loyalty to the US. The FBI began its investigation in 1952, but this was not the first time they had been interested in him. During the Second World War, Williams’ friend from his days at the University of Pennsylvania, the poet Ezra Pound, had broadcast anti-American and pro-fascist propaganda from Italy. In one of his broadcasts, he mentioned “ol’ Doc Williams of Rutherford, New Jersey.”8 The subsequent investigation of Williams correctly ascertained that he had no anti-American or pro-Axis sympathies.

The investigation of 1952 produced a file of 153 pages about Williams and his activities.9 In the late 1930s he had signed petitions and spoke at rallies advocating friendship between American and Soviet citizens, civil rights, and support for the republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. Politically conservative elements in the US wanted to use Williams’ appointment as a way to attack the Library of Congress and its financial support of artists. The FBI conducted interviews in Rutherford with the police chief, the town’s newspaper editor, and various teachers, as well as with academics all over the country. They uncovered no evidence that Williams was a “subversive.” He saw himself as “an American Democrat and a liberal and a virulent anti-fascist…at heart apolitical.”10

The FBI, under its chief, J. Edgar Hoover, pressured the Library of Congress to rescind Dr. William’s appointment despite his innocence. The story released to the press was that Williams’ poor health prevented him from accepting the position.

Dr. Williams was never told what was in his FBI file.

References

- William Carlos Williams. The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams, New York: New Directions Publishing, 1967.

- Carl Lindgren. Läkare med penna och patos, Stockholm: Carlsson Bokförlag, 2021.

- Richard Carter. “William Carlos Williams (1883 – 1963): physician-writer and ‘godfather of avant-garde poetry,’” Ann Thoracic Surg, 67(5), 1999.

- Lindgren.”Läkare.”

- NA. en.wikipedia.org. Red Scare-Wikipedia ND.

- NA. en.wikipedia.org. Red Scare-Wikipedia ND.

- NA. en.wikipedia.org Federal Bureau of Investigation-Wikipedia. ND.

- Williams. “Autobiography.”

- SP Sullivan. “He was one of Jersey’s most famous poets. The FBI worried he was a communist.” NJ.com, 2018.

- Sullivan. “One of Jersey’s.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan. He has long admired William Carlos Williams both as a poet and as a physician.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 2 – Spring 2022

Leave a Reply