Giovanni Ceccarelli

Rome, Italy

When Ferdinand Hodler met Valentine Godé-Darel, a thirty-five-year-old woman divorced from a Sorbonne professor ruined by gambling, at the Kursaal in Geneva at the end of 1908 or beginning of 1909, he was already a famous painter. His two paintings Nighta and Day,b in which “the same spirit permeates all things, manifesting itself through the rhythmic succession of time, symmetries and natural balances,” established him, along with Boeklin, as one of Switzerland’s greatest painters. Hodler was about twenty years older than Valentine, but the two quickly became lovers; she (la Parisiennec) became one of his models and Hodler painted several portraits of her, one of which (Lady with hat and featherd) was inspired by Matisse’s famous Femme au chapeau.e

At the end of 1913 a child, Paulette, was born, but almost at the same time, Valentine was diagnosed with uterine cancer. Despite two operations and radium therapy, which had only just been discovered, she died on January 25, 1915. During her illness, Hodler (who was married and involved with other models) was very close to Valentine, and in her last months painted her almost obsessively. An exhibition held in Zurich in 1976 brought together around sixty works (drawings, gouaches, oils) by Hodler in which the progress of Valentine’s illness was documented with dramatic precision. Hodler often indicated the date, including 24 January,f the last one in which Valentine was still alive, and those of 26 January,g in which her body appears motionless in death. This extraordinary series of images (“No one has ever done anything like this,” said Hodler2), became the subject of some medical considerations3, 4, 5 after it became public.

While Hodler was painting Valentine ill and dying, what was weighing on the two protagonists of this story? Hodler spent almost every day between November 1914 and January 1915 with the woman he loved. This was “the time of waiting,” a non-physical, non-measurable time, but a lived time nonetheless. It is what Henri Bergson6 defines as “la durée” (“duration”); a profound time in which one can do nothing but wait, is excluded from acting, and can only be in the present moment. One enters willingly or unwillingly into this time, which is also the experience of those who wait outside the operating theatre for the outcome of an operation on a loved one. It is a time experienced internally, becoming an “absolute” such as that experienced by the character Jaromir Hladik in Borges’ story7 for whom a moment becomes a year. In this time of complete mental absorption, one can truly come to understand our existence, even if “a rustling of leaves” can “make that eternal moment disappear.”8

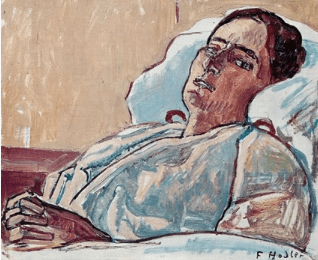

Into this time (which also recalls, but only in part, the waiting for Godot9), Hodler inserts his drawings of Valentine, thus making himself present to himself. It seems to be an act of breaking away; the passing of the days has become almost unbearable. Hodler’s drawings may simply be his way of expressing his “being there” at the side of the suffering woman, just as others were there who assisted by feeding her or, to recall Munch, “moving her pillows.”10 But Hodler paints Valentine’s face (Fig. 1), which is becoming, as the days pass, the face of suffering. It is a face, as Emmanuel Lévinas puts it, “naked before death,”11 and as such does not ask for sentimental pity but conveys the imperative not to be indifferent to death and suffering. From that face emanates a cry, again as Lévinas says, “silent, pre-conceptual, pre-linguistic,”12 which asks only for all our sensitivity. “Giving attention, giving our true attention to a person who is suffering, is a very difficult thing to do, and to succeed in it is almost a miracle,” said Simone Weil.13 Hodler paints that face, he makes an image of it; and an image is inevitably a thing that removes our attention from the suffering person.

Art becomes a means of detaching ourselves, of evading our responsibilities.14 We see Hodler’s work of art, but we no longer see Valentine suffering and dying. The waiting—the durée—should be left empty. Perhaps we should let go of our human desire to fill it with something that only serves to detach us from an unbearable sight. (Maurice Blanchot: “Waiting for waits without haste, leaving empty what is empty.”15) If one looks closely at these paintings, they give the impression of having been completed in a hurry, almost as if the painter realized that his marks were not capable of rendering the duration of Valentine’s suffering. Therefore one could only paint quickly, almost with the expectation that at the end of the painting the suffering would end. But as the suffering continued, one could only begin the process again, until the ultimate ending. Pain and death cannot be shared;16 by externalizing his experience in his art, Hodler shields himself and us.

In Hodler’s work we are not confronted with the actual death of a person from cancer, but with an allegorical fiction in the hall of an exhibition or a museum. This is demonstrated by the title of the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zurich in 1976, in which “Ein Maler von Liebe und Tod: a painter before love and death” came before the names of the protagonists. One might ask whether art, which here we owe to Valentine’s memory, but also to Hodler, without whom she would have been forgotten forever, should interfere with the very human process of suffering and death. When we offer our pity for the dying, we might ask: pity for whom?17

Works of art cited in the text

- a. F. Hodler: The night, 1889-1890, Kunstmuseum Bern.

- b. F. Hodler: The day, 1899, Kustmuseum, Bern.

- c. F. Hodler: La Parisienne (The Parisian) – Bildnis Valentine Godé-Darel, 1909, private collection.

- d. F. Hodler: BildnisValentine Godé-Darel mit Federhut (Valentine Godé-Darel with a hat) , 1909-1910, private collection.

- e. H. Matisse: Femme avec le chapeau (Women with a hat), 1905. Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco.

- f. F. Hodler: Die Sterbende Valentine Godé-Darel, Halbfigure im Linksprofil (The dying Valentine Godé-Darel, half-figure in left profile), jan 24, 1915. Kunstmuseum, Basel.

- g. F. Hodler: Die tote Valentine Godé-Darel (The dead Valentine Godé-Darel), jan 26, 1915. Solothurn Museum.

Bibliography

- Brushweiler J. “Ein Maler var Liebe und Tod: Ferdinand Hodler und Valentine Godé-Darel, ein werkzyklus 1908-1915′. Zurich, 1976.

- Schmidt K. “Ferdinand Hodler portrait series of the sick, dying and dead Valentine Giodé-Darel”. In: “Ferdinand Hodler, a symbolist vision”. Ed. By Schmidt K, Waker B.: Bhattacharya Stettler Th: Kunstmuseum Bern and Szépmuveszeti Museum Budapest, 2008, pp. 275-294.

- Ceccarelli G., Pretolani M., Pretolani E.. “Dying in art’. In: “L’assistenza al morente”. Sgreccia E, Spagnuolo A., Di Pietro M.L. (eds), Milano 1994.

- Pestalozzi B.C. “‘Looking at the dying patient: the Ferdinand Hodler paintings of Valentine Godé-Darel’. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 7, 1948-1950.

- Pestalozzi B.C. “Looking at the dying patient. The paintings of Ferdinand Hodler by Valentine Godé-Darel’. J. Clin. Oncol., 2003, 21 (9, suppl.), 74s-76s.

- Bergson H. “Durée et simultaneité. Fèlix Alcan ed. Paris 1922.

- Borges J.L. “El milagro secreto”. First publication on SUR, Feb 1943; afterwards in “Ficciones”, Buenos Aires: SUR, 1944.

- Benjamin W. “Storyteller’. In: ‘Selected writings’ vol. 3, 1935-1938. Eiland H. & Jennings H.W. eds., New York 2006.

- Beckett S. “En attendant Godot, Éditions de Minuit, Paris 1952.

- Héran E. “Le dernier portrait ou la belle mort. In: “Le dernier portrait” Héran E. & Bolloch J. eds. Paris 2002.

- Lévinas E. “God, death and time’. Columbia Univ. Press 2000, p. 168.

- Lévinas E. “Entre nous. Stanford Univ. Press, 1998.

- Weil S. “Attente de Dieu. First edition: La Colombe ed., 1950; afterwards Fayard ed. Paris, 1966.

- Lévinas E. “La rèalité et son ombre. In “Les temps modernes”, 1948.

- Blanchot M. “L’entretien infini. Gallimard, Paris, 1969.

- Bronfen E. “Over her dead body: death, femininity and the aesthetic’. Manchester Univ. Press, 1992.

- Goodwin J.S. “Mercy for killing: mercy for whom?” JAMA, 1991, 265, 32.

GIOVANNI CECCARELLI, M.D., PhD., (born 1933) is a pediatrician with a degree in art history (Sapienza, Rome University). He specialized at University of Pavia where he obtained in 1968 a “Libera docenza” (free teaching university degree). In 2010 (at seventy-seven years old) he obtained (magna cum laude) a degree in art history at Sapienza, University of Roma. Over the last few years, he has published Malattie di artisti (Diseases of artists), 2017, preface by J. Nigro Covre and F. Pierangeli; and Arte 1860-1960 per incolti curiosi (Art 1860-1960 for curious dummies, 2021). He is a widower, has two children, five grandchildren, and a great-granddaughter. He lives in Rome.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021 and Volume 13, Special Issue– Fall 2021

Leave a Reply