Michael Denham

New York, New York, United States

|

|

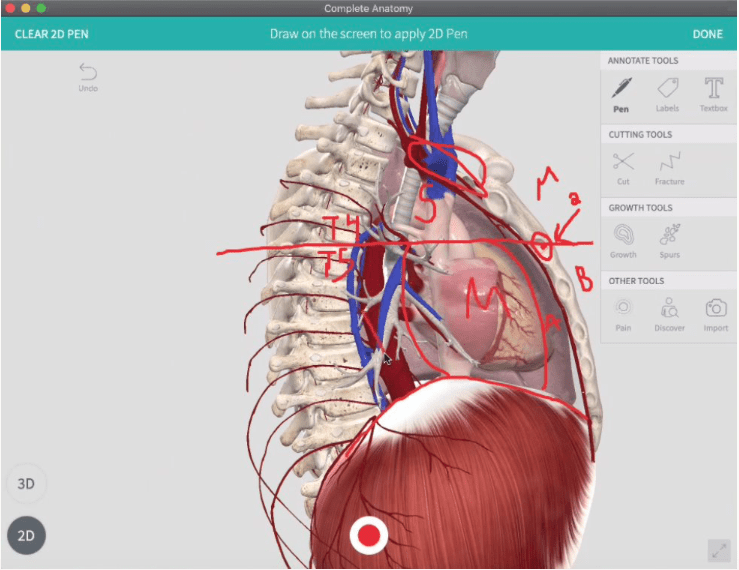

An instructor uses Complete Anatomy, a virtual anatomy software, to illustrate sections of the chest. By Michael Denham. |

As the COVID-19 pandemic emerged in early 2020, anatomy departments across the United States struggled to develop contingency plans to continue training the country’s future physicians. Would this year’s class of 22,239 medical students be the first in American history who could not learn gross anatomy on cadavers?

Many medical schools decided to maintain in-person dissection by dramatically limiting the number of students in the laboratory, keeping them far apart, and requiring masks. But some thirty of the approximately two hundred medical schools in the United States shut down in-person dissection completely, at least for the fall semester. Instead, they used digital technologies to mimic the experience of working with a cadaver.

Pivoting with such short notice was like changing the course of a cruise ship. Running an anatomy program is incredibly technical and involves a complex network of moving parts. Anatomy labs cost millions of dollars to build, and operating them requires coordination between body donation programs, educational faculty, sanitation staff, and services for embalmment and cremation. Although exact costs around maintenance and operation of these labs are usually kept private, programs often spend about $2,0001 per cadaver for the initial preparation and transportation of the bodies, with each cadaver teaching between four and eight students.

The pandemic forced faculty and students to adapt to new educational situations at an impressive scale, ushering in new investments in digital technology that may have permanent implications beyond a single class.

Videos of cadavers are publicly available on sources like YouTube, usually in the form of “prosections”—a process of examining dissections done by others. However, David Morton, an anatomist at the University of Utah, feels that many existing resources are outdated or suffer from poor video quality. In April of 2020, he began creating short videos of faculty teaching anatomy on cadaveric specimens.

Morton has considerable experience in making publicly accessible anatomy resources. His YouTube account of educational anatomy videos, The Noted Anatomist,2 has over 209,000 subscribers, and his videos have been viewed over 10.7 million times. Morton hopes to use his existing platform to share his newly developed series of videos.

When the pandemic made it clear that anatomy instruction would be disrupted, Claudia Krebs, an anatomist at the University of British Columbia, planned to mail out virtual reality headsets, which students could use to view and manipulate virtual models of the human body. She had been developing software for this with the intention of allowing students in rural communities to participate in remote anatomy sessions. But to respond to COVID-19, she would have to scale up her “little boutique project” from twenty rural students to over a thousand.

“I checked in February and March, and virtual reality goggles were sold out,” says Krebs, when interviewed about her experience. “I think there was a run on toilet paper and virtual reality goggles.”

She was forced to pivot. In May she began developing a platform that would allow students to view three-dimensional images of cadaveric specimens, which students would explore using a lab manual. Creating these images relied on a combination of 3D laser scanning and photogrammetry, a process of extracting 3D information from a series of 2D photographs.

Just a few months later, a new lab was being developed and deployed for use by hundreds of students across Canada each week.

As institutions struggled to retrofit their courses for the pandemic, there were mounting concerns about what would be lost in the education of this year’s first-year medical students. There were also signs of a generation gap, since older instructors who had been holding digital improvements at arm’s length—as merely adjunctive to dissecting cadavers—were forced to accede to their younger, more digitally inclined colleagues.

But many of the virtual tools were not quite ready to completely replace dissection. The sheer number of images and labels required to do that simply were not yet prepared—leading students to struggle for longer than normal to visualize an anatomical structure. One anatomy faculty member at a New York City medical school says she cannot believe the number of times faculty members have been forced to edit a virtual lab module on the fly by rapidly adding labels or altering information.

“It’s the little things, like that, that are so numerous and so overwhelming,” she says. “How many of those little things have we forgotten?”

Today, I wonder how much reverence for the human body is learned by directly working with cadavers. There’s a camaraderie to the sharing of VapoRub among peers to rub under noses to combat the smell of preservation agents slowing the decay of flesh, a bond forged across living and dead as analogies between preserved muscle tissue and prosciutto abound.

For many, the dissection of a donor’s body in an anatomy course grounds the first months of medical school in the hard realities of medicine: the messiness of flesh, the long hours spent standing on aching feet, and the ultimate outcome of death for us all.

This is not to say that death or tragedy begets some higher, more commendable illumination. Rather, clinical gross anatomy serves as an arena in which students encounter these issues early on, before facing them while caring for patients, potentially for the first time.

Quite simply, sometimes you are not ready to deal with a living person until you make mistakes on a dead one.

References

- Jeff S. Simpson. “An Economical Approach to Teaching Cadaver Anatomy: A 10-Year Retrospective.” The American Biology Teacher 76, no. 1 (2014): 42-46. Accessed August 12, 2021. doi:10.1525/abt.2014.76.1.9.

- Morton, David. The Noted Anatomist. YouTube Channel. YouTube. https://www.youtube/channel/UCe9lb3da4XAnN7v3ciTyquQ.

MICHAEL DENHAM, MPhil, is a third-year medical student at the Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. As an undergraduate, he studied Chemical Engineering and Economics at Louisiana State University before receiving a master’s degree in Health, Medicine, and Society from the University of Cambridge. His academic interests include health care delivery, clinical research, and medical humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 4 – Fall 2021

Leave a Reply