Anne Jacobson

Oak Park, Illinois, United States

|

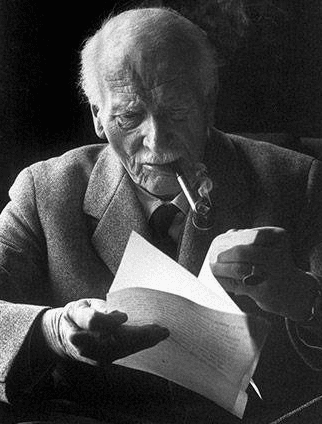

| Carl Jung. Photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Creative Commons. |

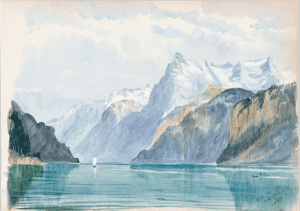

In the autumn of 1913, Carl Gustav Jung was traveling alone by train through the rust and amber forest of the Swiss countryside. The thirty-eight-year-old psychiatrist had been lately troubled by strange dreams and a rising sense of tension, but the snow-capped peaks of his beloved Alps soothed him as the train chugged past glacial lakes and sunlit valleys. Nature had always been a balm, even from his earliest childhood memories on the shores of Lake Constance.1,2

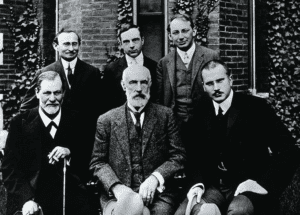

Jung had felt adrift and disoriented since his public and painful split with Sigmund Freud the year before. The two men had once seemed kindred spirits, talking for hours without rest the first time they met. Jung, who had trained and worked with Eugen Bleuler at the Burghölzli Psychiatric Clinic in Zurich, had long recognized that he differed from most of his psychiatric contemporaries in that he saw more to his patients’ psychological functioning than the classification and symptomatology of mental illness. His early work performing word association tests with institutionalized patients had caught the attention of Freud, a professional rogue himself, and the elder doctor had anointed the junior psychiatrist as heir-apparent to his new and controversial school of thought. But Freud had also positioned himself as a father figure to the young doctor and asked Jung to take an oath to forever maintain Freud’s sexual theory as the central doctrine of psychoanalysis.3-5

Even at that early stage in his career, Jung understood from his extensive clinical and research work and from his own rich inner experiences, that there were many factors and conflicts that molded the human psyche besides sex. Freud, after a series of letters and conversations, including two occasions where he worked himself up so mightily that he fainted and then accused Jung of a repressed wish to kill his father-figure, expelled Jung from his inner circle, leaving the young psychiatrist without a professional realm within or outside of academia.6,7

The years leading to this rupture had been stressful indeed; in addition to the tension with Freud, Jung had a growing practice as a psychoanalyst, conducted research, lectured at the University of Zurich, was asked to speak internationally, and had a growing young family at home with his wife, Emma.8 But the unrest he felt in the autumn of 1913 seemed different: “The pressure which I had felt was in me seemed to be moving outward, as though there were something in the air. The atmosphere actually seemed to me darker than it had been. It was as though the sense of oppression no longer sprang exclusively from a psychic situation, but from concrete reality.”9 The feeling had been growing more intense when, on the train ride through the idyllic Swiss countryside, he “was suddenly seized by an overpowering vision: I saw a monstruous flood covering all the northern and low-lying lands between the North Sea and the Alps . . . I realized that a frightful catastrophe was in progress. I saw the mighty yellow waves, the floating rubble of civilization, and the drowned bodies of uncounted thousands. Then the whole sea turned to blood.”10

|

| Bay of Uri, Brunnen. John Singer Sargent, 1870. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

When the same vision recurred two weeks later, this time accompanied by an inner voice telling him that these events would come to pass in reality, he began to wonder if he might be psychotic. More visions followed, continuing until the First World War broke out on August 1, 1914. While part of him still doubted his sanity, and he worried that he would end up like his philosophical and literary heroes Nietzsche and Hölderlin, he also had an “unswerving conviction” that he was “obeying a higher will” in his resolve to “try to understand what had happened” and how the activity of his own psyche might be related to the wider human experience.11 Thus began a period of inner work and self-analysis that would become the basis for the second half of his career and his most significant contributions to the field of psychology.

Jung’s work traversed the landscapes of anthropology, antiquity, mythology, philosophy, spirituality, art, religion, alchemy, literature, medicine, and psychology. Many of his contributions would ultimately figure most prominently in fields outside his own, for example, in Joseph Campbell’s work in narrative studies. Jung, however, primarily considered himself a psychiatrist, and during the sixteen years he engaged in the intense induction, analysis, and recording of his own fantasies, dreams, and visions in what would come to be known as Liber Novus, or The Red Book, he maintained an active clinical practice.12 “My patients brought me so close to the reality of human life that I could not help learning essential things from them,” he wrote. “Encounters with people of so many different kinds and on so many different psychological levels have been for me incomparably more important than fragmentary conversations with celebrities. The finest and most significant conversations of my life were anonymous.”13

Jung also engaged with the characters in his own vivid imagery, recording conversations with them in his journals and accompanied by his own rich, colorful drawings and paintings. He encouraged his patients to use the same technique as a way to uncover unconscious content and meaning. He believed that while it was important to have knowledge and understanding of psychological conditions to orient him in a particular direction, the deeper meaning and work of each person’s dreams and fantasies was individual. “I avoided all theoretical points of view and simply helped the patients to understand the dream-images by themselves, without application of rules and theories.”14

|

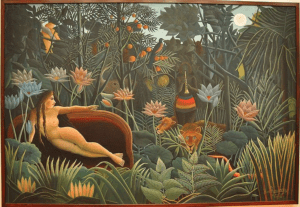

| The Dream. Henri Rousseau, 1910. MoMA. |

Simultaneously delving into the depths of his own inner world felt necessary but terrifying. “In order to grasp the fantasies which were stirring in my ‘underground,’ I knew that I had to let myself plummet down into them, as it were. I felt not only violent resistance to this, but a distinct fear. For I was afraid of losing command of myself and becoming a prey to the fantasies—and as a psychiatrist I realized only too well what that meant. After prolonged hesitation, however, I saw that there was no other way out. I had to take the chance, had to try to gain power over them; for I realized that if I did not do so, I ran the risk of their gaining power over me.”15

Jung recognized doctors’ need for awareness and understanding of their own conflicts, emotions, and unconscious processes while helping patients to do the same. This also requires an openness and ability to learn from patients. “The doctor is effective only when he himself is affected. ‘Only the wounded physician heals,’” he wrote. “But when the doctor wears his personality like a coat of armor, he has no effect. . . . It often happens that the patient is exactly the right plaster for the doctor’s sore spot. Because this is so, difficult situations can arise for the doctor too—or rather, especially for the doctor.”16 For this reason, he also advised that a therapist should have another person to help process what patients share, a practice that continues today. “Every therapist ought to have a control by some third person, so that he remains open to another point of view. Even the pope has a confessor. . . . Women are particularly gifted for playing such a part. They often have excellent intuition and a trenchant critical insight, and can see what men have up their sleeves. . . . They see aspects that the man does not see. That is why no woman has ever been convinced that her husband is a superman!”17

Jung agreed with Freud that dreams contain powerful clues to the unconscious and may help people heal from mental illness. However, Freud primarily used dreams to look for clues and representations of an individual’s repressed experiences from the past, while Jung believed that dreams could also help a person move forward and attain wholeness. He believed that dreams create a psychological compensation, which allows integration of an individual’s conscious and unconscious mind. In another significant departure from Freud, Jung emphasized dreams with symbolic figures called archetypes that are common to all of humanity. He engaged with scholars, medicine men, healers, tribal members, and literature and art from Africa, Asia, and African American and Native American communities to explore the presence of similar archetypes in diverse populations. “Big” dreams—dreams with vivid archetypes and symbols—were thought to connect a person to a deeper, more primal level of the psyche called the collective unconscious. These dreams and archetypes act as wisdom guides in the quest for wholeness and meaning in a process called individuation.18

|

| Carl Jung (front right) with Sigmund Freud (front left). Clark University, 1909. Public Domain. |

Individuation also includes integration of all parts of one’s personality. It was Jung who coined the terms introversion and extraversion, and defined four additional personality styles: sensation, intuition, feeling, and thinking, which form the basis for personality assessments that are still widely in use today, notably the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.19 While one function is dominant in each dyad, Jung believed it was important to develop and bring into consciousness the other parts of one’s personality rather than repress them. He called this process enantiodromia—“running the other way”—a term he borrowed from Heraclitus, who taught that everything eventually turns into its opposite. Command of all personality functions was thought to be the key to good mental health, but also to transcendence.20

Much of Jung’s work would today be considered spiritual or mystical as much as psychological. While he noted the importance and presence of religion as part of the human experience, he distinguished the personal encounter with a divine presence or higher power as something distinctly different from the constructs and rules of formalized religion. This distinction began with his own childhood experiences and failed attempts at conversation with his pastor father. Jung’s conception of the spiritual as an integral part of the human psyche might best be described as a search for meaning. “As far as we can discern, the sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a light in the darkness of mere being,” he wrote shortly before his death in 1961 at the age of eighty-six.21 “Meaninglessness inhibits fullness of life and is therefore equivalent to illness. Meaning makes a great many things endurable—perhaps everything.”22

Many of Carl Jung’s contributions remain, although often amended, referenced, developed, or, in the words of Joseph Campbell “suggestive, not definitive.”23 His research, writings, and thought body have contributed to technology (polygraph testing),24 psychological assessments (word association tests),25 personality tests, the addiction treatment model for Alcoholics Anonymous,26 psychotherapeutic techniques, mind-body medicine, and narrative theory.27,28 But perhaps his most enduring contribution to the reductionistic and science-only model of modern medicine is this gentle reminder: “The unexpected and the incredible belong in this world. Only then is life whole.”29

Notes

- Carl Gustav Jung, edited by Aniela Jaffe, translated by Richard and Clara Winston. Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 4th edition (New York: Random House, 1989), 210.

- Sonu Shamdasani, “Sonu Shamdasani Introduces the Red Book.” (2009; Rubin Museum of Art), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOKKCJsYqMw&t=430s.

- Carl Jung, A Life of Dreams, Part I: Wisdom of the Dream (1989; PBS), https://topdocumentaryfilms.com/the-wisdom-of-the-dream/.

- Jeffrey A. Lieberman, Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry (New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2015), 54-59.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 205.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 178-188.

- Lieberman, Shrinks, 58-9.

- Joseph Campbell, Introduction to The Portable Jung (New York: Viking Penguin, 1971), xi-xxiii.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 210.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 211.

- Shamdasani, Rubin Museum of Art.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 173.

- Ibid., 205.

- Ibid., 213.

- Ibid., 161.

- Ibid., 162.

- Kelly Bulkeley, “Jung’s Theory of Dreams: A Reappraisal, Part 1,” Psychology Today, March 23, 2020. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/dreaming-in-the-digital-age/202003/jung-s-theory-dreams-reappraisal-0

- The Myers & Briggs Foundation, https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/

- Campbell, Introduction to The Portable Jung, xxvi-xxviii.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 380.

- Ibid., 391.

- Joseph Campbell, “Jung, the Self, and Myth,” Campbell Foundation. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hcogiUUNnM.

- Carl Jung, A Life of Dreams, Part I.

- Campbell, Introduction to The Portable Jung, xiii.

- Ian McCabe, Carl Jung and Alcoholics Anonymous: The Twelve Steps as a Spiritual Journey of Individuation (Routledge, 2015), 3-11.

- Christopher Vogler, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 4th edition (Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2020), 26.

- Emily S. Darowski and Joseph J. Darowski, Joseph J. “Carl Jung’s Historic Place in Psychology and Continuing Influence in Narrative Studies and American Popular Culture,” Swiss American Historical Society Review: 2016 Vol. 52 : No. 2 , Article 2.

- Jung and Jaffe, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, 416.

Works Cited

- Bulkeley, Kelly. “Jung’s Theory of Dreams: A Reappraisal, Part 1.” Psychology Today, March 23, 2020. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/dreaming-in-the-digital-age/202003/jung-s-theory-dreams-reappraisal-0. Accessed April 28, 2021.

- Carl Jung: A Life of Dreams. Part I: Wisdom of the Dream. PBS, 1989. Accessed March 23, 2021 at https://topdocumentaryfilms.com/the-wisdom-of-the-dream/.Darowski, Emily S. and Darowski, Joseph J. (2016) “Carl Jung’s Historic Place in Psychology and Continuing Influence in Narrative Studies and American Popular Culture,” Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 52 : No. 2 , Article 2.

- Jung, CG and Jaffe, A. Memories, Dreams, Reflections. New York: Random House, Vintage Books Edition, 1989.

- Jung, CG. The Portable Jung. Edited by Joseph Campbell. New York: Viking Penguin, 1971.

- Lieberman, Jeffrey A. Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 2015.

- McCabe, Ian. Carl Jung and Alcoholics Anonymous: The Twelve Steps as a Spiritual Journey of Individuation. 1st ed., Routledge, 2015, doi:10.4324/9780429472695.

- Myers-Briggs Foundation. https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/.

- Shamdasani, Sonu. “Sonu Shamdasani Introduces The Red Book,” Rubin Museum of Art, 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XOKKCJsYqMw&t=430s. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- Vogler, Christopher. The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers, 4th edition. Studio City: Michael Wiese Productions, 2020.

ANNE JACOBSON, MD, MPH, is a family physician, writer, consultant, and editor. Her published works may be found in Hektoen International, The Examined Life Journal, The Journal of the American Medical Association, in the anthology At The End of Life: True Stories About How We Die, and others. A collection of her writing may be found at www.thewritetowander.com.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply