Hugh Tunstall-Pedoe

Dundee, Scotland, UK

|

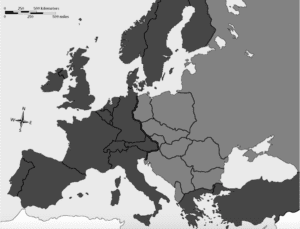

| Iron Curtain as described by Churchill 1946. Edited from original. Original by BigSteve via Wikimedia. (CC BY 1.0) |

In 1946, Winston Churchill named the political barrier appearing between the Soviet bloc and the West the “Iron Curtain.” It lasted until 1991. I met or crossed it several times.

The first time was around 1950. The family flew a war-surplus box-kite on Parliament Hill, overlooking Hampstead, London. The reel broke. The kite crashed into a tree in a stately garden. The doorplate had Cyrillic and English inscriptions: “Soviet Trade Delegation.” A friendly Russian climbed the tree, but the kite was along a rotten branch. Decades later, the delegation figured in the expulsion of a hundred Soviet diplomats. Our kite had fallen among spies! They allegedly continued espionage and inciting sabotage, despite warnings. By 1971 our friend must have moved on.

The Cold War always risked warming up. During the 1956 Hungarian uprising, a cousin sat in a British (NATO) tank in Germany, its engine running, ready to move in if Austria’s neutrality was violated.

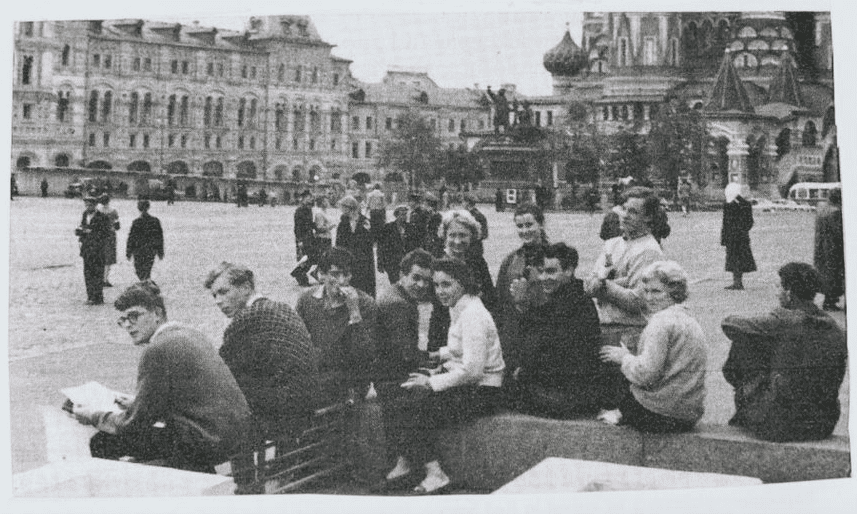

In 1960, Russia opened to tourism for campers. I joined a self-selected, Cambridge University student expedition, bent on satisfying our curiosity about our Cold War antagonist. Another such expedition included a future vice-president of the European Commission—we rescued his group in Russia by bringing over replacement tires from Helsinki for their badly prepared little car. Our group was eleven medical students, plus a linguist—framed and deported during a subsequent stay—thereafter a professional Russia-watcher. We had advice from a college Master, a former wartime scientific counselor at the Moscow embassy. We visited Leningrad and Moscow and used royalties from mathematics texts of my father’s, published there without permission, to fund a group visit to Romeo and Juliet at the Bolshoi Ballet, with caviar and vodka in the interval.

Following lengthy spadework, we had eventually received recognition as a “delegation” and had an intensive tour of medical and academic institutions, with a warm, kindly reception and interesting dialogues. We also attracted hangers-on: fierce patriots arguing politics; spivs who wanted to buy our clothes, shoes, and western currency; others who were curious, wanting to be friendly; but also, dissidents, one, a young man living an exceptional existence. Son of a famous war hero, he even had his own car. He recounted facing starvation in infancy in the siege of Leningrad and being fed through Winston Churchill’s wife’s—Clementine’s—popularly supported British Red Cross “Aid for Russia Fund.” He invited us to the home of his aunt, an English teacher. A reception at the Moscow embassy included designated Russian medical students—our friend charmed himself past the guards.

|

| Arrival in Red Square, Moscow, August 1960—a celebratory drink (author extreme left). Photo by D. Tunstall Pedoe. |

In preparation, I had asked if visiting Russia would prejudice our chances of government employment. I received a formal document, bound with colored ribbon, in flowery language stating, “not in itself.” Our senior tutor said the query must have gone to the secretary of state himself. Afterwards, our visit was praised by embassy staff—fresh air for them, in Moscow’s looking-glass world. Our enthusiasm for a reciprocal visit to Britain was frustrated (support was required from the National Union of Students and we belonged to the separate British Medical Students Association), so it was a no-go.

I crossed the Iron Curtain repeatedly from the early 1970s for WHO collaborative medical research meetings. Tutoring at a cardiovascular epidemiology seminar in Esztergom, Hungary in 1974, was memorable for a nearby Danube bridge across to Czechoslovakia, dynamited in World War II and not yet restored—contact, allegedly, had to go via Russia. Later, in Poland, the watcher woman on our floor of the hotel asked for help in obtaining western insulin for her sick son. With severe disenchantment, products of a totalitarian monopoly become objects of distrust.

East Berlin, in 1976, memorably hosted a Cold War Incident. The German Democratic Republic (East Germany), having just been recognized through membership of the United Nations and consequently the WHO, was hosting its first meeting. The topic was prevention of ischemic heart disease and I was the rapporteur.

Professing progressive socialism, East Germany appeared to have been frozen in a 1940s time warp. Shops displayed improbable posters of German and Soviet soldiers at the conclusion of the Second World War, embracing and kissing. A group photograph caused the photographer to be led away by a policeman—the building behind was verboten to photograph. He returned later. The first day included a reception at the ministry of health. A dinner-jacketed attendant opened the door, indicating a silver salver heaped with loose cigarettes—help yourself! The health minister was a jovial, rotund man, his deputy an immaculately groomed, severe-looking woman reminiscent of our own health minister, Mrs. Barbara Castle, then passionately hugging the British National Health Service (NHS) like a toddler with a kitten. The deputy minister delivered the welcome, an elderly man translating. After many references to the ever-closer relationship with their fraternal ally, the Soviet Union, she launched into a diatribe against western medicine. “If you cannot pay for your treatment, you are left to die in the gutter.” A paroxysm of coughing came from an English secretary working for the WHO, gallantly sustained.

|

| Berlin: Checkpoint Charlie, through the Iron Curtain. Photo by Roger W. Taken August 19, 1963. Via Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0. |

“Hugh, what am I to do, what am I to say?” our chairman, scheduled to give the vote of thanks, asked me in distress while drinks circulated. An erudite, sensitive, and much-loved man, he was an erstwhile refugee from Nazi Germany who had trained in Britain, worked in America, and was then based in Switzerland. “What a remarkable speech, given what was being said in this city forty years ago,” I suggested. Later he replied, “How nice to be here, and thank you very much.”

“Is it always like this?” I asked the interpreter. “You cannot seriously believe that I work for these people!” was his indignant response. I hailed a Budapest colleague of six years—he ran away without responding, a frightened rabbit. Not so my Warsaw colleague. “Hugh, now you see what nonsense we have to put up with every day.” He assured me that the deputy minister believed what she said. She was circulating, along with a Russian minder. Hearing that I planned remonstrating, my friend summoned a waiter, offering me extra drinks.

My turn came: “When I get back to London, I am going to ask the health minister, Mrs. Barbara Castle, to invite you over so you can see what the British National Health Service is really like.” My intended sarcasm was lost in translation—she appeared pleased. Her ever-closer Soviet ally distanced himself from her. “I have seen the NHS in Scotland, and it is very good.” I imagined the two formidable women dueling—I would have relished being a fly on the wall. I heard later that the deputy minister had a severe dressing-down from a Norwegian, whose CV included gaining positive results in a trial of primary prevention of heart disease based on behavioral change—he tolerated neither behavioral relapses nor this nonsense.

On our last day, our colleagues invited us to the Charité Hospital. We encircled a person lying rigidly at attention whilst Herr Professor spoke at considerable length over him and the apparatus without making any personal contact. As the group moved on, I lingered to smile and say “Danke schön.” He was very animated receiving this recognition.

I returned home to many distractions, including redrafting my report, but also finding that Barbara Castle was no longer health minister. My plan had been aborted.

In the 1980s, I ran a quality control center in Dundee for the WHO MONICA Project. My test case-histories were sent out recurrently from Geneva as “MONICA Memos” and the recipients mailed codings to Dundee. A bundle of post arrived, encircled with rubber bands. Codings from East Germany were on top of several letters from there, addressed throughout Britain to, presumably, communist-front organizations: “mothers for peace,” “babies for peace,” “bubbles for peace”… an intriguing mixture.

In 1987 there were proposals for the WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators’ Meeting to be held in East Berlin. It was argued that it was East Germany’s turn, since a MONICA Congress had been held in West Germany the previous year. I reminded the East German cardiovascular diseases officer in Geneva of what had happened previously and forewarned him that, rapporteur or not, with any recurrence, I would walk out.

There was no Cold War diatribe. I heard that a young Mediterranean colleague with a strict Catholic upbringing crossed Checkpoint Charlie in a state of abject terror, presumably fearing the Antichrist, whilst my own hitch on entry was that nobody knew what a laptop computer was. It was memorable otherwise: for my inability to obtain flight times out of West Berlin from the East Berlin hotel; for buying some East German currency in West Berlin, then finding I could not use it because the hotel insisted on payments in US dollars and it was valueless when I returned; and for a British sentry at Checkpoint Charlie denying there were any cab-ranks nearby, then my finding one just around the corner, presumably off his beat.

It was an isolated and isolating world.

Three years later, after nearly half a century, the world’s political tectonic plates moved, old fissures began closing, and new ones opened. European “workers’ paradises” such as East Germany disappeared, largely forgotten. Sadly, fake news continues in ever-greater volumes, from west as well as east.

Did things change completely? In 2003, WHO published a monograph on the WHO MONICA Project that I had designed, edited, and written, with sixty-eight collaborators. Twenty copies went from Dundee to each of the thirty-three MONICA centers, many previously behind the Iron Curtain, including Moscow and Novosibirsk (Siberia). Uniquely, the two parcels to Moscow were returned, unopened—without explanation.

HUGH TUNSTALL-PEDOE, MA, MD, FRCP (London and Edinburgh), FFPH, FESC, semi-retired, is emeritus professor and senior researcher in the Cardiovascular Epidemiology Unit, Dundee University, Scotland, UK. He studied at Cambridge University and Guy’s Hospital and followed a career in medicine and cardiology in London before becoming a researcher in cardiovascular epidemiology. He moved to Scotland in 1981 to head a research group on cardiovascular disease, was Rapporteur of the WHO MONICA Project from 1979-2003, and initiated the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort (SHHEC) whose follow-up he continues. Latterly he was involved in teaching medical ethics.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Winter 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply