John Raffensperger

Fort Meyer, Florida, United States

Willis Potts and Percival Pott were both highly skilled surgeons, prolific authors, and contributed to the surgical care of children.

Percival Pott (1714–1788)

Percival Pott, at age fifteen, apprenticed to Edward Nourse, a surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. He paid 210 pounds for his seven-year apprenticeship. Pott attended lectures at the barber-surgeon’s hall and became Nourse’s prosector for anatomical demonstrations. The court of Examiners of the Barber Surgeons Company awarded Pott the “Grand Diploma,” the equivalent of board certification in 1736. The length of surgical training at that time was not too different from today. In 1744, Percival Pott became an assistant surgeon and five years later a full surgeon at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. He had a large practice, served St. Bartholomew’s for fifty years, and trained many surgeons, including John Jones of New York, who wrote the first American textbook of surgery.1 He married Sarah Cruttendon, the daughter of the director of the East India Company. The marriage must have ensured his place in London society.

In 1756, Pott was riding to see a patient when the horse threw him to the ground and he suffered a compound fracture of the tibia. Several of his surgical colleagues recommended amputation, the safest treatment for a compound fracture at that time. Pott convinced Edward Nourse, his mentor, to clean the wound and splint the fracture. He survived with his leg intact.2 During his convalescence, he commenced a career in medical writing that led to fourteen major monographs on subjects ranging from hernias to head injuries and diseases of the eye.

The same year as his injury, he published the first edition of A Treatise on Ruptures and an Account of a Particular kind of Rupture Attendant on Newborn Children. The second edition of this monograph was 198 pages long and had a chapter on congenital hernias.3 Based on anatomical dissections, Pott described the failure of closure of the procesus vaginalis as the cause for congenital or indirect hernia. He describes a child with a hernia:

If the subject is an infant, the case is not often attended with much difficulty or hazard; the softness and ductility of their fibers generally rendering the reduction easy as well as the descent; and tho from neglect or inattention it may well fall down again, and yet it is as easily replaced, and seldom causes any mischief: I say seldom because I have seen an infant, one-year-old, die of a strangulated hernia which had not been down two days, with all the symptoms of intestinal mortification.

If the reduction was difficult, Pott induced relaxation with warm baths, flexion of the thighs, or bleeding to the point of swooning. When the child was limp from the loss of blood, one could reduce the hernia. After reduction of the hernia, Pott applied a bandage or truss to prevent the hernia from recurring, and with time the sac might close, effecting a permanent cure.

An operation was indicated if the hernia could not be reduced. Pott cut through the skin and fascia, made a small incision into the hernia sac, and then inserted a probe to avoid injury to the intestine. Imagine, how difficult it must have been to replace loops of intestine into the abdominal cavity in an awake, terrified, squirming infant. But Pott apparently accomplished this feat. He closed the deep layers of the wound and the opening of the hernia sac with a running suture. Pott was the first surgeon to save the testicle during hernia repair. He observed that the peritoneal sac was the source of pathology but later surgeons closed the internal ring and performed fascial repairs in children. Almost two hundred years after Percival Pott’s observation, Willis Potts cured pediatric hernias with simple ligation of the sac.4

Pott first used the term “puffy tumor” in his monograph on head injuries:5

If the symptoms of pressure, such as stupidity, loss of sense, voluntary motion, etc. appear some few days after the head has suffered injury from external mischief, they do most probably imply an effusion of fluid somewhere—in the substance of the brain, in its’ ventricles, between its’ membranes or on the surface of the dura mater, and the formation of matter between it and the skull, in consequence of contusion is generally indicated and preceded by one [sign] which I have hardly ever known to fail: I mean a puffy, circumscribed and spontaneous separation of the pericranium from the skull under the tumor.

Pott advised immediate operation to drain the fluid or remove diseased bone. One of his patients was a nine-year-old boy who suffered a blow on the head during a game of cricket. The boy had a swelling over his forehead and had “lost his sense.” Pott, with a trephine and elevator, raised the depressed fracture. The boy recovered.

The puffy tumor—a fluctuant, swollen mass over the forehead—is more likely caused by osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with sub-periosteal pus. The etiology is usually a neglected frontal sinusitis which may be complicated by a cavernous sinus thrombosis or a brain abscess. It is now rare, but as in the days of Percival Pott, requires urgent surgical intervention.6

The fractured tibia suffered by Pott after he was thrown from a horse may not have been a “Pott’s fracture,” but in his 1768 monograph on fractures and dislocations, he lucidly described what is now termed a Pott’s fracture of the ankle:7

If the tibia and fibula both be broken, they are both, generally displaced in such a manner, that the inferior extremity, or that connected to the foot, is drawn under that part of the fractured bone, that is connected with the knee; making by this means a deformed unequal tumefaction in the fractured part and rendering the broken limb shorter than it ought to be.

He went on to say, “Extremely difficult to put to rights and still more to keep it in place.” Pott included a drawing of the displaced foot and a skeletal illustration of the displaced fractured tibia. Without the benefit of X-rays, his illustration is amazingly accurate and reflects his detailed knowledge of anatomy.

John Charnley’s description of the Pott’s fracture in his classic, “Closed Reduction of Common Fractures” is almost identical to that of Percival Pott. He even mentions the difficulty of closed reduction and maintaining the position of the bones.8

There is no better example of Percival Pott’s clinical acumen than his observations on deformities of the vertebrae and paralysis of the lower extremities.9 Physicians at that time attributed the deformity and paralysis to trauma or lifting a heavy weight. Pott was skeptical of this theory because infants and children had the same symptoms with no history of injury. At autopsy, Pott discovered carious vertebrae, thickened ligaments, and a quantity of sanies (pus) between the rotted bones.

A chance conversation with a colleague who had drained pus from a patient with curvature of the spine and lower extremity palsy with good results confirmed his suspicions. He “made an issue by an incision on one side of a projection” in an infant with a curvature in the middle of his neck and paralysis. At the end of a month, the infant was “manifestly better” but died with smallpox. At autopsy, Pott found the vertebrae larger than usual and more open and “spongy.”

Pott operated on more patients to drain para-vertebral abscesses, in some instances with:

results that greatly exceeded my most sanguine expectations, by restoring several most miserable and totally helpless people to the use of their limbs, and to a capacity of enjoying life themselves, as well as being useful to others.

Antibiotics essentially eliminated tuberculosis of the spine by the middle of the twentieth century. It is still a problem in developing countries, and is known as Pott’s disease.10, 11

Percival Pott was the first to connect cancer to an environmental toxin when he attributed cancer of the scrotum to soot in the scrotal rugae of chimney sweeps.12 At that time in England, young, impoverished boys were forced to work in chimneys where they were burned, bruised, and almost suffocated. Pott took pity on these poor urchins and made detailed examinations of their lesions. The cancer was a painful sore with hard, rising edges that invaded the dartos, the testicle, and then traveled up the spermatic cord to the lymph glands in the groin. Eventually, the cancer invaded the abdomen. This elegant description of a squamous cell carcinoma attests to Pott’s knowledge of anatomy and pathology. He said:

If there be any chance of putting a stop to or preventing this mischief, it must be immediate removal of the part affected; I mean that part of the scrotum where the sore is, for if it be suffered to remain until the virus has seized the testicle, it is generally too late even for castration.

Potts published his work on scrotal cancer in 1775. Parliament enacted a bill that chimney sweeps must be at least twenty-one years old. The law was not enforced until 1875.

Percival Pott is still today, one of the great names in surgery. The many eponyms involving his name have helped countless students remember obscure diseases.

Willis J. Potts (1895–1968)

Willis Potts was born in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. His father died when he was twelve years old. He and his older brother worked on a farm to support the family. In 1914 he entered Hope College, operated by the Dutch Reformed Church in Holland, Michigan. In 1917 he joined the Army and served in France. After the war, he graduated from Hope College but lacked a chemistry credit for admission to Rush Medical College in Chicago. At that time the pre-clinical years at Rush were at the University of Chicago. Potts managed to complete the chemistry course in eighteen days and was admitted to medical school. He was married, had two children, and worked in the school cafeteria to support his family.

In 1925 he was the Logan Fellow in Surgery at Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago and then practiced general surgery in Oak Park, Illinois. In 1930 he studied surgery in Germany, then practiced general surgery at West Suburban Hospital in Oak Park and Presbyterian Hospital. He also was a volunteer surgeon at Children’s Memorial Hospital.

A father of one of his patients related this story. During the Depression, Dr. Potts had done an appendectomy on his son. The fee was $150. The father said, “How about $75, cash?” Dr. Potts said, “It’s a deal.”

The first suggestion of his interest in children’s surgery was a paper on the treatment of congenital pyloric stenosis at Children’s Memorial Hospital. From 1932 to 1937, mortality for this condition was reduced from 12.8 percent to 3.5 percent, partly because of the increased use of subcutaneous fluids and blood transfusions in very sick patients.13

In 1942, at the age of forty-seven, Potts again volunteered to join the Army. He served as the surgeon-in-chief of the 25th Evacuation Hospital on the Island of Espiritu Santo. Doctors, nurses, and technicians dug post holes, mixed cement, laid floors, and built the hospital. Dr. Potts and the orthopedic surgeon built an elevated platform for a tent to house patients.

They cared for as many as 200 hundred soldiers a day, suffering from burns, malaria, dengue fever, limbs shattered with shrapnel, and hepatitis. In letters to friends at Presbyterian Hospital, Potts wrote:

We are on a tropical island in a coconut grove, where it is hot all the time. I would gladly trade a thousand coconuts for one little snowbank and a million more for walking down familiar corridors.

Last night we had a rather unique experience of taking out an appendix by flashlight. Right in the midst of the operation the ominous eerie wail of the air raid siren split the night. In an instant the entire camp was immersed in absolute darkness. Even the starlight is absorbed by the dense foliage of the coconut trees. Making darkness impenetrable. The trouble of connecting the emergency lighting system and closing all the shutters hardly seemed worthwhile so we finished the job with a flashlight shining in the wound. All went well.

We have been operating almost four months and our wound infection rate is less than three percent. By infection, I mean redness and purulent exudate, no matter how small. I am sure of the percentage because I have looked at all the wounds.

A few days ago, the clinical conference issue of the Children’s Memorial Hospital arrived. I’m like the old man who sees visions and dream dreams and think with happy memories of a host of people and a multitude of incidents at the Children’s.14

While in the South Pacific, Potts resolved to practice pediatric surgery. In 1945 he was appointed surgeon-in-chief at Children’s Memorial Hospital. He immediately went to Boston Children’s Hospital to observe the work of William Ladd and Robert Gross, who had established the specialty of pediatric surgery. While in Boston, Potts witnessed an autopsy on an infant who had died with cyanotic heart disease. The infant was considered too small to have a subclavian artery-pulmonary artery anastomosis.

Upon his return to Chicago, Potts developed a technique for a direct anastomosis between the aorta and the pulmonary artery in cyanotic infants. He also invented the first clamps that held blood vessels without slipping or crushing the vessel. This was a major contribution to vascular surgery.

Potts performed the first aorto-pulmonary anastomosis on Friday the thirteenth, September 1946. The patient was twenty-one months old, weighed only eighteen pounds, and was intensely cyanotic. The operation relieved the cyanosis and she lived for sixty-two years.15 He developed or improved operations for congenital heart disease as well as other birth defects such as esophageal atresia, inguinal hernia, and imperforate anus.

Thomas Baffes, one of his trainees who became a prominent Chicago surgeon, wrote this about Potts’ surgical technique:

Dr. Potts brought a passionate devotion to intellectual integrity and a firm conviction that solutions to clinical surgical problems absolutely had to be based on a firm foundation of the knowledge of the basic sciences. Potts was an absolute ‘bear’ on precise technique and gentle handling of tissues.16

Potts wrote extensively to promote pediatric surgery and established the second training program in pediatric surgery in 1946. His trainees included a president of the American Medical Association and an editor of the Journal of Pediatric Surgery.

Perhaps his most enduring contribution to the surgical care of children is his book The Surgeon and the Child.17 This unusual surgical text is filled with his humanity and sense of ethics. The first chapter of this engaging book opens with:

With no language but a cry children are asking for better surgical treatment of their ills and are begging for more thoughtful attention to the congenital deformities it was their misfortune to be born with.

Long before philosophers took up medical ethics, Potts addressed the thorny, often controversial issues of how to manage an infant with major, incurable deformities. He consulted Catholic theologians when the parents of an infant with an open bladder, intestinal obstruction, and indeterminate sex were uncertain about what to do. The answer was that one may but not need to use extraordinary means to preserve life. Extraordinary means was defined as anything very costly, unusual, painful, or difficult. The family decided not to treat the infant, who died. Dr. Potts was very firm in his opinion that the parents know best.

In his third chapter, “The Heart of a Child,” Potts ended with:

The mystical heart of a child is a precious and beautiful thing. It is marred only by the wounds of a thoughtless and not too intelligent world.—I am convinced that the heart of a child sunned by love, security and understanding will be able to withstand the storms of illness and pain.

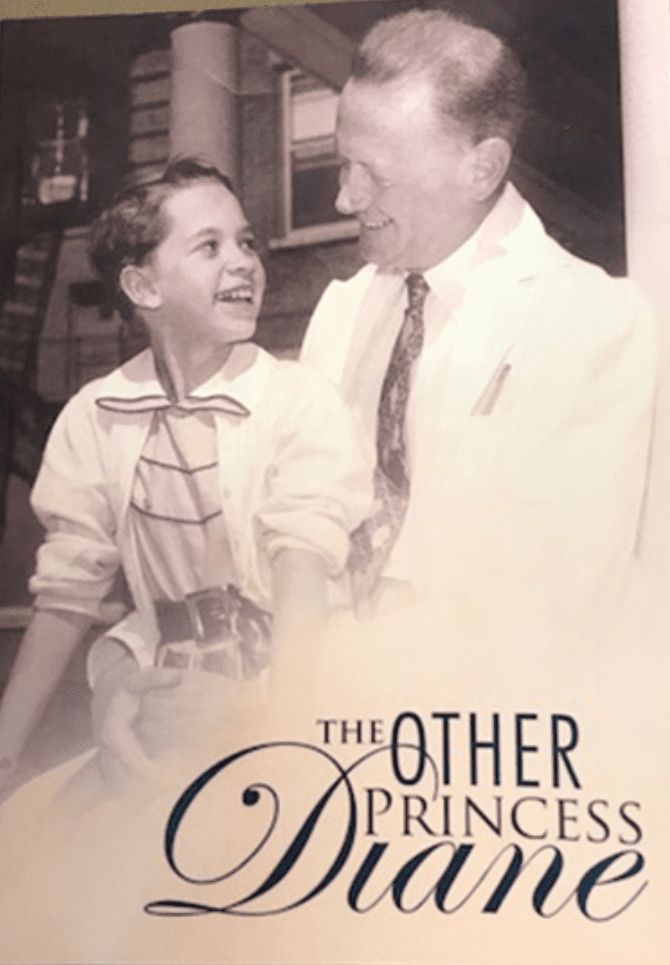

In person, Potts epitomized the word “charisma.” He was tall and distinguished, and when not in a scrub suit or a white coat, he wore a suit, vest, and tie. He was a wonderful speaker, had an infectious laugh, and could charm donations to the hospital from tight-fisted bankers.

Two surgeons, Percival Pott and Willis Potts, separated by two hundred years, an ocean, and half a continent, shared a compassion for children, developed new operations, and improved surgical care.

References

- Peltier, L. F., MD., PhD, “The Classic Chirurgical Works of Percival Pott, F.R.S., Surgeon to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, A New Edition, with his Last Corrections, From the internet, Wolters, Kluwer Health, Inc. Copyright, 2020, Open access.

- Dobson, J., Percival Pott, Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons, England, 50, [1972]: 54-65.

- Pott, P. Senior Surgeon to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital; An Account of a Particular kind of Rupture, Frequently Attended on Newborn Children and Sometimes met with in Adults viz. That in Which the Intestines or Omentum is Found in the Same Cavity with the Testicle. 2nd edition; London, printed by W. Clark, L. Hawes and R. Collins M. DCCLXY from Internet Archive.

- Potts, W.J. Riker, W.L., Lewis, J.E.; The Treatment of Inguinal Hernias in Infants and Children, Annals of Surgery, 132, [1950], 566-574.

- OBSERVATIONS on the Nature and Consequences of Those Injuries in which the Head is Liable from external violence. By Percival Pott, F.R.S. and Surgeon to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, Printed for L. Hawes, W. Clark, R. Collins, in Pater-Noster Row, M.dcc.lxviii.

- Suwan, P.T. Mogal, S. Chaudhari, S. “Pott’s Puffy Tumor: An Uncommon Clinical Entity”, Case Reports in Pediatrics, Vol. 2012, Article, JD 386101, Open Access, Hindawi, Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 3.0).

- Some few general remarks on Fractures and Dislocations by Percival Pott, F.R.S. and Surgeon to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital; London, printed for L. Haws, W. Clark and R. Collins in Pater Noster Row M. dcc.lxix; pages 57-59.

- Charnley, John, Closed Reduction of Common Fractures, Chapter 16; From Cambridge.org/Potts Fracture.pdf.

- Pott, P. Some remarks on that Kind of Palsy of the Lower Limbs, Which is Frequently Found to Accompany a Curvature of the Spine, and is Supposed to be Caused by it, Together with It’s Method of Cure. London, J. Johnson, 1779.

- Kumar, R., Dillip, G., Samyanshis, S. Spinal Tuberculosis: A Review, Journal of Spinal Cord Medicicne; 2011, September, 34[5] 440-454.

- Benzagmolut. M., Said, B., Chakour, K. El Faiz Chaoul, M., Potts Disease in Children; Surgical Neurology International, 11-January 2011:21.

- Brown, J.R., Thornton, J.L. Percival Pott, [1714-1788] and Chimney Sweepers’ Cancer of the Scrotum; British Journal of Industrial Medicine, 1957, 14, [1] pgs. 68-70.

- Potts, W.J. Congenital Pyloric Stenosis, Mississippi Valley Medical Journal, Vol. 61, May, 1939, pgs. 84-87.

- Letters in the archives of Rush Medical School.

- Potts, W.J. Smith, S. Gibson, S. Anastomosis of the Aorta to the Pulmonary Artery; Certain types of Congenital Heart Disease; Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 22 #11, 1946, pgs. 627-631.

- Baffes, T.G., Willis J. Potts, His Contributions to Cardiovascular Surgery; Ann. Thoracic Surgery, 44, July 1987, pgs. 92-96.

- Potts, W.J. “The Surgeon and the Child,” W.B. Saunders and Co. Philadelphia and London, 1959.

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, graduated from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in 1953, interned at the Cook County Hospital, spent two years in the Navy and returned to Cook County for training in general, thoracic, and pediatric surgery. He was on the attending staff at Cook County until 1970, when he went to the Children’s Memorial Hospital and eventually became the surgeon in chief. He has written textbooks, works of medical history, and novels. After retiring from active practice, he sailed across the Atlantic and back, then served as a voluntary pediatric surgeon at Cook County.

Leave a Reply