Xi Chen

Rochester, New York, United States

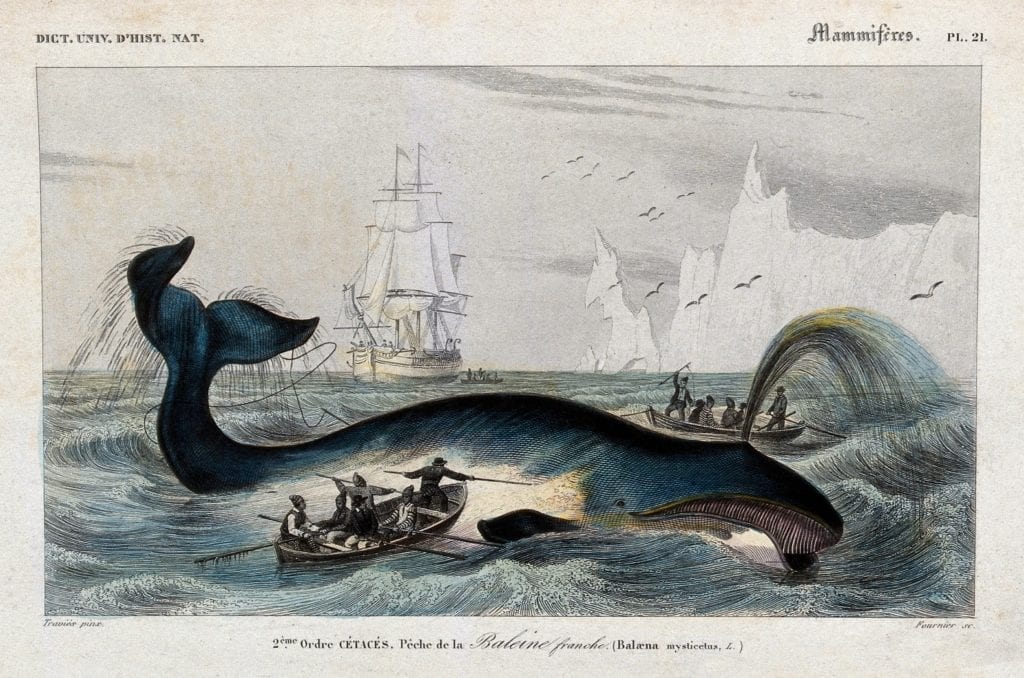

In the summer months before my first year of medical school, I unfurled the pages of Moby Dick. Immersed in the novel’s adventurous spirit and Shakespearean prose, I followed the narrator from the piers of Nantucket into the Atlantic and waded through Captain Ahab’s quest for the legendary white whale. I was ostensibly reading for fun—but in truth, what got me to read Melville’s classic was a rising and distressing awareness of the stage upon which I was about to walk. My future career in medicine loomed large in my mind, and I knew that the time for reading literary fiction was about to disappear. In a fervor, I rushed to the novel’s lonely epilogue and like the watery world that swallows up the anti-hero Ahab, the story washed over me. I was left with only a diluted sense of what it was all about as I stepped into my first day of anatomy lectures.

In line with my first reading of Moby Dick, the first semester of medical school was strangely underwhelming. Not in the depth of the knowledge I needed to traverse, which held true to the metaphor that medical school is like drinking water out of a fire hydrant. It was in the purpose and meaning behind the journey. I slowly discerned that medical education was not unlike the business of nineteenth-century whaling, in which encounters with actual whales were few and far between. Instead, they were devoted to self-regimented routine, concentration, and even boredom. The patients I met were paid actors; real patients in the hospital gave me the feeling that I was a burden rather than a locus for understanding and connection. The mark of my personal ambitions—contact with people in search of healing—weighed me down with a sad anxiety and became as distant and insoluble as Ahab and his self-destructive hunt.

I returned to school from the winter holidays and experienced a change of pace. On my schedule, puncturing the daily onrush of lectures about biochemistry and genetics were weekly seminars organized by the hospital’s division of medical humanities. Students could select from a list of topics ranging from art history to the history of psychiatry. Shrugging off the choice as another colorless medical school requirement, I picked the one seminar that gave me extra time for lunch. It was a class on a subject that in retrospect receives surprisingly little attention: pain. The seminar demanded adjustment. Learning shifted from our familiar, expansive lecture hall to an airless conference room in a remote sector of the hospital. Our professor, a philosophically-minded neurologist, assigned us hefty readings and assignments requiring us to answer unfamiliar questions about the worst pain we had ever experienced or our opinions on opioid prescription. These topics became the subjects of our seminar discussions, during which my classmates and I fumbled around trying to express what we knew and, more often than not, what we did not understand about the clinical, historical, and cultural nature of pain.

At first I was resistant to seriously studying pain in a disciplined way. The two-hour meetings felt like a distraction, the opioid crisis a footnote to the basic sciences that I needed to memorize for my exams. What changed my thinking was a quote that our professor shared from essayist and philosopher Elaine Scarry’s seminal work The Body in Pain: “to have great pain is to have certainty; to hear that another person has pain is to have doubt.”1 It seems almost cliché to say that the communication of pain, one of the most common reasons for a doctor visit, is obscured and frustrated by language’s limited capacity to connect people. However, I began to realize that pain is not a mere sensation or biological phenomenon but a window to help me better understand the suffering of others.

I started to rethink Ahab, not as the mythical tragic figure, but as a person in pain. He experienced great trauma in the loss of his leg but also his sense of personal identity. Pain, as David Morris wrote, is that completely illegible aspect of “the most basic human experiences”3 that demands translation and interpretation. It is this search for meaning that motivates the creation of narratives and stories like Moby Dick. And that is what I love about novels, how they transform the silencing force of pain, what Scarry would call “world-destroying,”1 through written language into experiences both universal and deeply personal. The emptiness I felt reading the narrator’s lonely epilogue was really doubt, which stemmed from my being unprepared to receive another’s pain.

And this, I have realized, is what medical school is for. What often feels like memorizing mind-numbing facts is the learning of a new language. The acting and the standardized patients are a chance to step outside of myself, to be someone who I am not: a doctor. A doctor is someone who receives a patient’s story, with all the pain and suffering and doubt that comes with it, translates that into medical language, and then relays a plan back to the patient. That plan can be a treatment for the pain, or it can be suggestions for how to live with the pain. Like dedicated readers of novels, doctors work with patients to create hope and possibilities from their stories, and through this connection offer healing. Pain narratives, even those described in great works of literary fiction, are expansive resources for this kind of radical compassion. In this respect, Ahab’s death was not just a great story—it was a gift.

References

- Scarry, E. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1985.

- Melville, H. Moby-Dick, A Longman Critical Edition. Bryant, J. and Springer, H., eds. New York: Pearson Longman; 2007.

- Morris, D.B. The Culture of Pain. Berkeley: University of California Press Books; 1991.

XI CHEN is a medical student studying at the University of Rochester. He is currently writing a collection of personal and academic essays about trust and meaning making in the relationships between patients and their physicians. His work has been featured in Entropy and murmur.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021

Leave a Reply