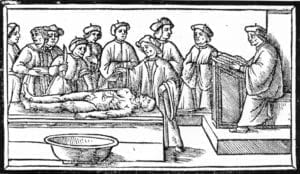

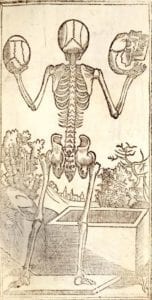

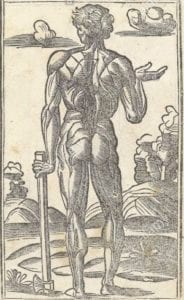

Berengario da Carpi was the most important anatomist of the generation preceding the so-called Anatomical Trinity of Vesalius, Fallopio, and Eustachio. He is regarded as one of the founders of scientific anatomy, challenging the reliance on ancient texts and emphasizing the primacy of direct observation based on dissecting the human body. A prolific author, he was first to illustrate anatomical texts with images made from woodblock prints. His fame rests largely on his commentaries and abridgments of the works of the fourteenth century anatomist Mondino dei Luzzi, his treatise on neurosurgery, and his observations on the anatomy of the brain and other organs.

Already in his time, Berengario was regarded as a great man, but even then his reputation was sullied by his bad temper, ruthlessness, and avarice. Prone to engage in violent confrontations, he participated in several physical assaults and even robberies, but was never convicted on account of his influence and high connections. When syphilis, the “French Disease,” struck Italy in 1494, he was among the first to use mercury, but was accused of charging excessive fees, insisting on being paid in advance, and becoming exceedingly rich. At one time he was condemned to have his nose cut off for speaking insultingly about the Duke of Ferrara, but got away with having a fine paid on his behalf. As one insisting on the primacy of observation over the authority of Galen, he claimed to have himself dissected several hundred heads, and was even accused of performing vivisection.

Berengario was born around 1460 in the small town of Carpi near Modena, the son of a reputable barber-surgeon from whom he learned much about the human body. As a young man he had a classical education, studied medicine at the University of Bologna, graduated in 1489, and practiced both as physician and surgeon. His patients included several illustrious members of the Medici family, notably Lorenzo II de Medici, Duke of Urbino, whom he treated successfully in 1517 for a fractured skull sustained in battle. This led him to publish in 1518 a monograph, De fractura, in which he emphasized the unity of medicine and surgery in practice, recommending treating patients according to six criteria: food and drink, exercise, rest and sleeping habits, evacuations, sex, and control of emotions.

Though recognized as a skilled practitioner, he refused the honor of being physician to the Pope. Instead, he went to Bologna in 1504 as professor of surgery and anatomy, and remained there as a popular teacher for almost a quarter of a century. When visiting Rome in 1525 on a request to treat a cardinal suffering from cancer, he was amply rewarded, given a painting by Raphael titled St. John in the Wilderness, and became a very rich man. Around 1526 he left Bologna and then became court surgeon to Alfonso d’Este, Duke of Ferrara and husband of Lucrezia Borgia. He died around 1530, but the exact date of his birth remains unknown.

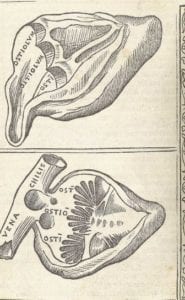

At Bologna, Berangario made many important anatomical observations. He described the horseshoe kidney, the small bones of the inner ear, the thymus, pancreas, cecum, appendix, and sphenoid sinus, and gave good descriptions of the heart valves and the cartilages in the larynx. He made many contributions to neuroanatomy, described the pineal gland, the choroid plexus, the ventricles of the brain and their connections with one another. He showed that nerves were solid structures, not tubes conveying vital fluids from Galen’s rete mirabilis, a hypothetical network of blood vessels at the base of the brain that he was never able to find and whose existence he disproved.

Berengario da Carpi is remembered as one of the first to deny the authority of Galen and was appreciated by sixteenth century anatomists as the restorer of the proper study of the human body by dissection. In the view of one of his illustrious successors, Gabriele Falloppio (1561), his work marked the beginning of what Vesalius subsequently perfected.

Leave a Reply