Valeri Lantz-Gefroh

Texas, United States

I am an actor, director, and acting teacher. And my theater is a medical school in Texas.

“Wait, what?”

My life in the last decade has been full of, “Wait, what?” The answers to that question have brought me profound appreciation for many things—but especially the expansiveness of theater training.

I was teaching acting at Stony Brook University when Alan Alda came into my life. He wanted to create an improvisation program to help scientists engage with the public and connect more clearly and authentically. Although I knew next to nothing about science, I was asked to help design and launch the improvisation program, which became a cornerstone of the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science.

Suddenly I was teaching in very different classrooms—at the National Science Foundation, National Academy of Sciences, NASA, and dozens of top medical schools, hospitals, and universities. I met graduate and medical students, post docs, faculty, doctors, nurses, veterinarians, senior researchers, Nobel Prize winners, folks who talk to Congress, and folks who struggle to talk to their families at Thanksgiving. Improv helped them recognize the person at the other end of the conversation and remember that before they crossed the threshold of knowing, they too spent a lot of time saying, “Wait, what?” about science

In 2010, I met and worked closely with Evonne Kaplan-Liss, MD who began her career as a journalist. As a patient herself with a lifelong chronic condition, she felt a different pull and returned to medical school to become a pediatrician. At the Alda Center, our paths intersected. We taught and traveled together and found a common passion and interest in bringing these ideas to medical schools.

We taught in tandem and where my discipline ended, hers took over, allowing our participants to understand the principles of theatre, storytelling, and journalism through the lens of medicine. Evonne knew from experience that these big ideas of connection, empathy, listening, story, and compassion could change the course of medical education.

Most medical schools believe communications training is important—and while that investment of time may seem reasonable, the curriculum of medical schools is deeply protected and stubbornly entrenched. Communication is taught in fits and starts—with little or no integration. Yet, so much of a doctor’s primary work is interacting with people. They race from room to room meeting patients whose lives depend on knowing and understanding what is wrong and what they can do about it. If only there were a way to solve this.

Last year Evonne was hired to serve as the Assistant Dean of Narrative Reflection and Patient Communication in a new medical school at Texas Christian University and University of North Texas Health Science Center. The dean, Dr. Stuart Flynn, is a revolutionary whose mission is to train doctors to become Empathetic Scholars™. Despite society’s rapid advances in technology, the most accurate diagnosis still happens by taking a history and performing a physical exam. To keep up with medical knowledge students must become lifelong learners—and be taught impactful new ways to sit with their patients and listen. Evonne is the first dean-level administrator in the country dedicated to communication. Every week through all four years, these future doctors will not only think about and practice medicine, but will also learn to be effective at communicating with their patients and colleagues. I have been hired to be the artistic director.

Why does a medical school need an artistic director?

This kind of integrated, longitudinal training has never been done before. It requires a new model. We are developing a conceptual framework and curriculum called The Compassionate Practice™ rooted in the method of Constantin Stanislavski. How do you analyze a character? How do you identify an objective and a conflict? How do you connect when you need to? How do you disconnect when the “show” is over and you have just lost a patient? We will draw from journalism, public health, diversity, wellness, psychiatry, and communication studies. This is a work in rapid progress that will be completed by the collaborative efforts of brave, innovative people who make a theater production team look tame.

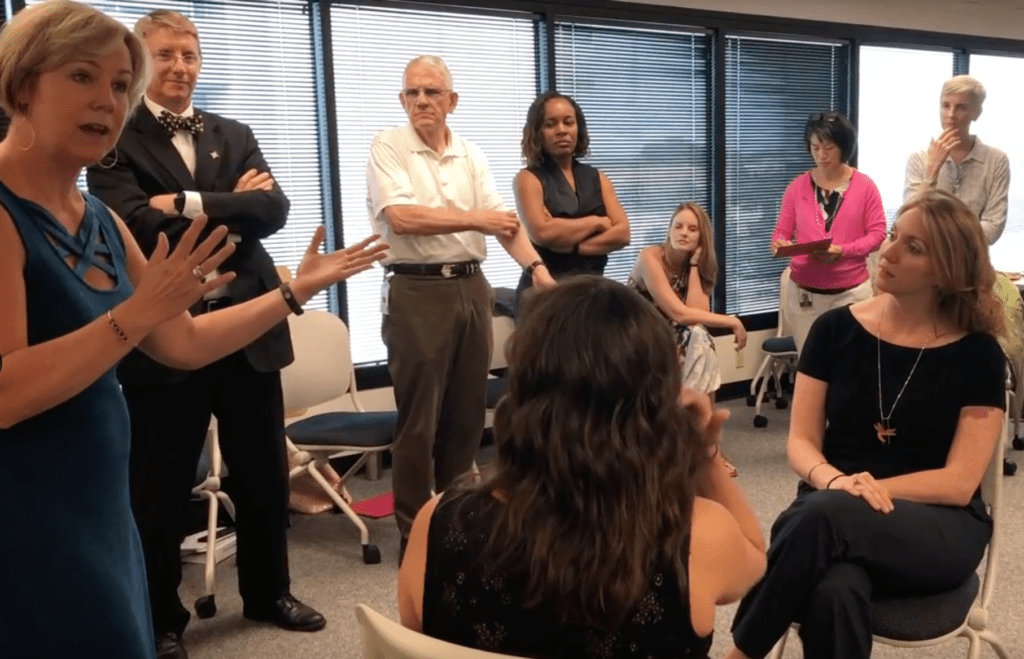

A two-day boot camp has trained a team of physicians who will coach our medical students as they traverse the challenges of their education. The camp will launch a year-long process that will help them to think differently about coaching than they do about doctoring. Danika Franks, our dean of student affairs, musing over the emotional discoveries of the day said: “If only there were a place where you could learn how to do these important things! They aren’t taught anywhere!” I smiled. “Actually, they are taught in drama school.”

Another physician challenged us, “I’ve got medicine to think about, now I’ve got to slow down and think about this too?” We gently pushed back: Everything new is difficult and time consuming. It gets easier. It is a creative process, find what is right for you.

Just two days later, that same skeptical doctor shared with our team an experience she had with a patient and the choice she made to shift out of her customary routine of telling the patient what to do and instead used deep listening and compassion. It meant her patient was handed back the decision-making process for her health. It also allowed the doctor to experience an important moment of human connection that makes medicine rewarding. In just two days theater helped her do that.

This is my theater now and it is also my unexpected gift. It is a new kind of rehearsal with global implications. It has helped me to see how much bigger theater can be off the stage. And we who educate theater artists can benefit ourselves, our academic missions, our students’ career paths, and their sense of self-worth when we help them recognize the expansiveness of what we learned in drama school. The theater mantra “never give up your dream” needs to evolve to include the world stage. Our unique studies honed skills that connect us all on a human level and it is time to open up the lens and look more fully at what we know. By doing so, we might see that there are different paths that we can help our students walk and celebrate as successful careers in the arts.

Lifelong learning. Yes, and. Listen. Connect. Breathe.

VALERI LANTZ-GEFROH is the artistic director at the TCU and UNTHSC School of Medicine.