Kathryn Taylor

San Francisco, California, United States

|

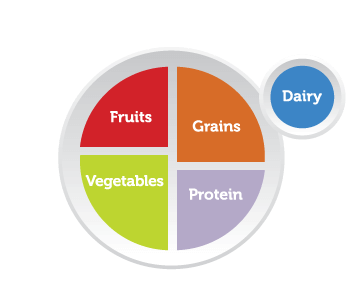

| MyPlate illustrates the five food groups that are the building blocks for a healthy diet, as recommended by the U.S. government. |

I do not floss daily. And I have poor sleep hygiene—I am always starting into the blue-light, back-lit screen before I go to bed. My vegetable intake is so-so.

But now, as a newly minted primary care physician, I find myself in a peculiar place—I have become the presenter of lifestyle modifications, a purveyor of well-being.

I saw a six-year old patient, Miguelito, in clinic last week. He was a strong-willed, leniently disciplined child who balked at the idea of vegetables, oral hygiene, and bedtimes. So upset had he become by tooth brushing, he once had gone on strike for a month. His mother argued she had been too tired to cross the picket line, and let his poor teeth marinate in sugar for thirty days. He abhorred all vegetables—they had tried an expansive variety to no avail. And, each night, she reported, he ran himself into a frenzy, then watched games and TV on a phone, often going to bed after 11 pm, sometimes midnight.

We had a lot of ground to cover.

I started off with diet, the lowest-of-hanging fruit, so to speak. “Have you heard of ‘My Plate’?” I started cheerfully, pulling an educational sheet from the room’s filing cabinet. Soon, however, my voice began to peter out. I floated out of my body and found myself looking down upon a young resident prattling on.

In truth, if I had been square with you, Miguelito, I started my day off with oily hash browns and eggs, which are poured from large plastic bags, from the hospital cafeteria. For dinner, take yesterday for example, I ate a slice of old cake, followed by a day-old half of a burrito.

And my apologies for the long-winded “no-screens at bedtime” spiel. What I meant was no screen, singular. I usually have multiple screens—an iPhone in one hand and laptop on the covers as I watch Netflix each night.

After a three years’ hiatus from professional dentistry, it turns out I have three cavities. And yes, here I am espousing the importance of regular oral hygiene. Do YOU have a dental home? Turns out I don’t have one either! It was very complicated with changing insurances. “But you should brush and floss each morning and evening!” I hear myself say chirpily through my rotten smile.

I send Miguelito and mom off with a copy of a healthy diet, a list of local dentists, and a goal to decrease screen time to one hour a day.

The plan I had outlined for Miguelito I know well—following it is my current new year’s resolution. It is uncanny—sobering—the similarities between our health goals.

Doctor Me is full of good intentions and confident proclamations regarding the importance of eight hours of sleep and square meals, while Actual Me struggles with the same healthful predicaments.

Do as I say, Miguelito, not as I do.

Doctors may have grappled with chemistry, physics, anatomy, and pathology, but how does class-taking qualify us to offer instruction on a healthful life? I would argue medical school and residency training, on the whole, teaches and reinforces unhealthy habits. The rigor of the training makes it difficult to exercise regularly, eat healthily, and sleep near enough. Balanced lifestyles, filled with the practices we are taught to teach, have been difficult to come by for nearly a decade.

In many ways, doctors have proven to be less healthy than the general population. As a bunch, we get divorced more, commit suicide more, and abuse substances more. One in three docs has no regular medical care themselves, not to mention we are notoriously bad patients when we are seen. Forty percent of primary care doctors do not meet the federal physical activity guidelines they champion for their patients.

Sure, I have read studies on the impacts of regular, moderate cardiovascular exercise on heart and brain health, and can recommend exercise to patients, but I have not been able to actualize that recommendation into my own life. I have read studies on the impact of sleep on function, but that does not mean I slept more than six hours before I saw you in clinic today.

And so I feel I have waded in the uncomfortable waters of well-intentioned duplicity. I offer ways to improve healthful living, as if I have—or could!—enact those changes in my own life.

Which makes me wish deeply that medical students and doctors received more training not only about the objectives of healthy behaviors, but the “how” of achieving them.

To the first point, most doctors do have some degree of training in medical school in assessing stages of change and in motivational interviewing, the art of asking open-ended questions and directing non-judgmental discussion around modifying a specific habit. But I feel hungry for much, much more of it. I cannot help but feel this training was nominal, given the daily use of these skills in both clinic and hospitalized patients.

I was required to memorize the number of carbon atoms in each molecule of the Krebs cycle for semesters on end as a pre-med and medical student, while only a handful of hours was dedicated to describing how to foster behavioral change. Within the biopsychosocial model of medicine, the “bio” part still claims, or one could say monopolizes, the focus of pre-medical and medical curricula.

Things are changing. For example, the MCAT, the standardized test all pre-medical students must take to apply for medical school, introduced new psychology and sociology content in 2015. Residencies, including the one I am lucky enough to attend, take far deeper curricular dives into motivational interviewing, helping us practice proven, high-impact ways to help patients stop smoking and using substances. Palliative care, and the sweeping tide of national awareness around death, also incorporates many of the “soft skills” traditionally overlooked in medical training such as leading family meetings, dealing with confrontation, and processing grief.

For now, to Miguelito and to the patients like him, I offer what medical advice I can, as non-judgmentally as possible. I still fear the patient who, after a discussion about sleep (or diet, or exercise for that matter) looks me dead in the eyes and asks, “Is that what you do, doc?”

To which, I suppose the only answer is honesty, and a generous supply of humility. That I am always looking to improve my own healthy habits. And that I can, with each encounter, be reminded and motivated to live the life I would want for my patients and for myself.

KATHRYN TAYLOR is a second-year resident at the University of California-San Francisco in Family and Community Medicine.

Winter 2018 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply