Gregory M. Rutecki

“…progress is the retrenchment of diseases.”1

“In 1870, physicians could do little to cure…A hundred years later they intervene…in many…diseases. In a single century…understanding of disease increased more than in the previous forty centuries combined.”2

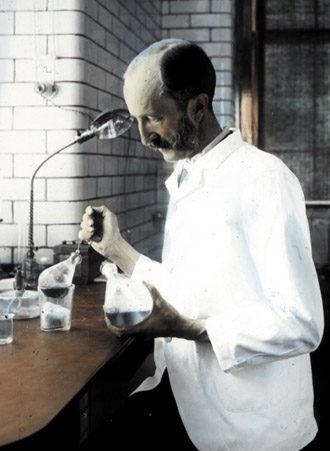

in his Laboratory

At the fin de siècle, American Medicine acquired a Promethean fire. Weapons would be forged against a heretofore impervious enemy—shielded by the armor of miasmas. Infections were thought to be a result of decaying animal matter escaping from sewers, carried by the winds.3 In 1873, asked whether typhoid was “infectious,” Austin Flint said it was borne aloft by “morbific emanations from sewers, cess-pools, and drains.”4 In 1876 he opined, “It is…claimed…that…Causation of certain diseases by…organisms of microscopic minuteness has been demonstrated…the demonstrative evidence is not complete.”5 A “Germ Theory” would finally expose a microbial universe. American Medicine was forced into cataclysmic change. Saranac Sanitarium, a hospital that retrenched tuberculosis–was one of the first American Hospitals to enrich Clinical Practice through Medical Science and Education. The founder, Dr. Trudeau led an American Clinical-Scientific Renaissance.

Proving Tuberculosis is an Infectious Disease

“Dr. Koch believes…Tuberculosis is a contagious disease…We confess to some skepticism (sic) regarding the facts.”6 (1882)

“People say there are bacteria in the air, but I cannot see them.”7

European Germ Theory fanned flames of a medical revolution. Although the only diseases proven contagious in 1881 were anthrax and relapsing fever, tuberculosis (TB) was added in 1882, and by 1900, so was plague, botulism, dysentery, cholera, glanders, diphtheria, typhoid, malta fever, tetanus, as well as staphylococcal, streptococcal, gonorrheal, pneumococcal, and meningococcal infections.8American progress would not be straightforward.9,10 In 1878, Dr. James Whittaker submitted a questionnaire to 250 “leading physicians” in America, asking whether TB was contagious. The results split: 126/250 responded yes.11 Eventually, naysayers like Austin Flint and William Welch converted sometime in the 1880s. One medical historian said, “The sudden appearance of the germ explanation in articles on diseases in the medical publications then (1880s) is almost a mystery.”12

Germ partisans warred with those from the old school. In 1882, Dr. Formad presented a paper insisting tuberculosis was not contagious. He “met rough treatment at the hands of his colleagues.”13 He revisited the claim at the National AMA meeting in 1884 and debates were “acrimonious.”14 Polarity regarding TB’s infectivity led to the formation of the American Association of Physicians in 1886. Forty-five charter members included Austin Flint, Edward L. Trudeau, William Osler, William Councilman, Edward Janeway, Silas Weir Mitchell, and William Welch.15

Trudeau survived TB, diagnosed by Edward Janeway while he was a medical student.16 He retreated to the mountains for healing, returning without active disease.17 His restoration to health made him a subscriber to science and germ theory. He founded a hospital at Saranac Lake to treat consumptives. How he was consumed by Koch’s postulates lends insight into dramatic medical changes occasioned by science.

He began by subscribing to The American Journal of Medical Sciences, The Medical News, and the Medical Record.18,19 He read a German to English translation of Koch’s Postulates, observing it was “The most far-reaching, in its importance to the human race, of any original communication.”20 He returned to medical school learning to stain, culture, and inoculate animals. His mentor, Dr. T. Mitchell Prudden, described the state of affairs, “Pathological Laboratories were rare in this country, and such as did exist were usually small corners in the ‘dead house’ of some hospital.”21

Saranac Lake’s Hospital: A Novel Medical Practice Consistently Informed by Science

The medical science of Trudeau’s era established fundamental precepts through testing. Regarding micro-organisms, mountain air was proven to be a natural barrier to their viability. Culture media were exposed to diverse locales.22 What made mountain air unique? Microbes per meter of air at Hotel Dieu in Paris—exemplary of urbanization—led to a contaminated atmosphere with 79,000 colonies/m3 of air. In contrast, mountains limited microbial growth to a single colony! “Extreme cold and high altitude render air aseptic…The invalid…is surrounded by a zone of pure air, which separates him…from the germ pervaded world.”23

It was left to Trudeau to extend observations to M. tuberculosis. One hurdle remained. The Captain of all These Men of Death was inevitably fatal. When was told he had TB Trudeau said, “I think I know something…of the man who…is told he is to be hanged on a given date, for in those days pulmonary consumption was considered as absolutely fatal.”24 Further discoveries engendered hope. In Vienna, Dr. Heitler reported observations from 16,562 autopsies.25 Seven hundred and eight subjects had healed tubercular patches suggesting TB could be contained by natural defense mechanisms. Heitler implied the “Office of physicians should be to assist nature.”26 Trudeau devised an experiment.27 Fifteen rabbits were divided into groups of five. Group 1 subjects were inoculated with M. Tb and placed in cramped quarters with limited food. They were “urbanized.” Group 2 control rabbits were crowded together as Group 1, but without inoculation. Group 3 was inoculated, but released on a sparsely inhabited island with a surfeit of food. Four of five Group 1 rabbits died of TB. Group 2 rabbits survived. One of the Group 5 animals died of TB! Furthermore, Koch himself had observed, “tubercle bacilli are killed by an exposure to direct sunlight varying in length from a few minutes to several hours.”28 Sanitarium treatment found its scientific direction.

Standing on the Shoulders of First Generation Medical-Scientists

“Between the mid-1860s and the mid-1880s…American physicians began to articulate a…program for reconstructing medicine on the foundation of experimental science…it urged…relationships among therapeutic practice…and professional identity…as an integral part of a new medical ethos.”29

Trudeau championed a clinical-scientific method that has persevered, continuing into contemporary practice. His clinical practice was informed by “bench to bedside” iterations:

“A young college student has come…(with) persistent cough and …loss of weight…on examination of the chest I could find nothing… but I was so keen about my…knowledge in staining…that I subjected every patient to this test…I found the germ…in the expectoration… this young man had a serious (pulmonary) hemorrhage in the classroom.” 30

He educated others regarding his “Evidence-Based Medicine,”

“A Dr. D’Arignon…asked me about ‘germs…convince me’…I will send you 5 numbered samples and if you tell me which ones came from tuberculosis cases, I will believe it…Three contained bacilli…He had lost his contempt for germs.”31

Trudeau also realized sanitaria were not final pieces to a puzzle containing a cure for TB. As a scientist, he tested whether M. Tb could be killed without harming its host. As a clinician, he sought greater diagnostic sensitivity, attempting to identify the bacillus’ presence prior to overt lung disease. He tried to develop a vaccine against TB. He attenuated cultures using soluble products from dead surface bacilli, sterilized products, and a host of filtered materials.32 He was unable to produce immunity after trials in multiple animal models. A vaccine for TB has still not been achieved.

He investigated tuberculin as a diagnostic and therapeutic agent.33 He was able to serially inject individuals with tuberculin to identify those with latent disease. He followed a cohort—comprised of individuals suspected to have incipient infections, but without evidence for TB in stained sputa. Those reacting to tuberculin with fever developed disease later. Tuberculin is still similarly utilized today. Even though Koch claimed tuberculin was therapeutic, Trudeau explicitly disagreed with the master. His lab model was “Rabbits…inoculated in the anterior chamber of the eye…’with live bacilli’…(these) animals (were) injected with glycerin extract of the (dead) tubercle bacilli,”34 and Trudeau wrote,

“Treatment by injections of tuberculin…undoubtedly… aggravates the disease…my own attempts at the production of artificial immunity in animals by… inoculation of tubercular products have proved… unsuccessful.”35

Also, long before the value of systems was appreciated, he created a first generation of tuberculosis nurses. “The next activity undertaken by the institution in its development was to educate as special tuberculosis nurses some of the young women patients in whom the sanitarium treatment had arrested the disease…a graduating class of thoroughly trained nurses.”36

Finally, and of great import, Dr. Trudeau was the epitome of compassion. At a time when physicians the likes of Oliver Wendell Holmes37 went to France to learn medicine from the Europeans, men like Trudeau and Osler role-modeled a distinctively American medical compassion. The famous Parisian physician Guillaume Dupuytren was described, “if his orders are not immediately obeyed, he thinks thinks nothing of striking his patient…A very favorite practice of his…is to make a handle of the noses of his patients…(the patient) is immediately seized by the nose and pulled down to his knees.”38 In contrast, Trudeau was called the “Beloved Physician.” He received 1000 cards of gratitude at his retirement party.39 Robert Louis Stevenson, his own patient, praised him, “Trudeau was all the winter by my side, I never spied the nose of Hyde.”40 Trudeau once said,

“Tuberculosis looms up as an ever-present and relentless foe. It robbed me of my dear ones…it shattered my health. I stood the death beds of many of its victims whom I learned to love…yet the struggle with tuberculosis…has enabled me to make the best friends a man ever had.”41

The ideal Hospital Practice of today—combining science with a clinical acumen informed by research, practiced with compassion, and nurtured by evidence-based iterations began in America as a result of the Germ Theory and a newly minted scientific age. The first generation of physician-scientists in America—men like Edward L. Trudeau–blazed a trail we should aspire to as physicians. It was the beginning of the end for the Captain and many other diseases.

References

- Solomon A. Far From the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity. Scribner, New York, 2012, page 221.

- Hudson R.P. Disease and its Control: The Shaping of Modern Thought. Praeger, 1987. Page 121.

- McMahon D.E. & Rutecki G.W. In Anticipation of the Germ Theory of Disease: Middleton Goldsmith and the History of Bromine. The Pharos 2011; 74:5-12.

- Flint A. Relations of water to the propagation of fever. Public Health Papers and Reports, 1873 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed April 25th, 2012.

- Evan A.S. Austin Flint and his contributions to Medicine. Medicine 1958; 32:224-241.

- Shrady E. The Medical Record 1882; 21:547-48.

- Ellison D.L. Healing Tuberculosis in the Woods: Medicine and Science at the End of the Nineteenth Century. Contributions to Medical Studies 1994; 41:44.

- Ibid., Hudson R.P., page 163.

- Richmond P.A. American Attitudes toward the Germ Theory of Disease (1860-1880). Journal of the History of Medicine 1954; 9:428-454.

- Tomes N. American Attitudes toward the Germ Theory of Disease. J Hist. Med. Allied Sci. 1997; 52: 17-50.

- Whittaker J.T. The contagion of consumption. The Medical Record 1878; 17:91

- Ibid. Richmond N., page 82.

- Formad H.F. The bacillus tuberculosis and the etiology of tuberculosis: is consumption contagious? Philadelphia: JB Lippincott. 1884, accessed at http://pds.lib.harvard.edu, June 6th, 2012.

- Ibid., Formad H.F.

- Transactions of the Association of American Physicians, 11th Session, April 30th—May 1st, 1896.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 20.

- Trudeau, Edward L. An Autobiography. Lea and Febiger, 1915, pages 89 ff.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 152.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., pages 36-37.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 175.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 7.

- Notter Lane J. “Air” in Hygiene and Public Health (Vol. 1). Philadelphia, P. Blakiston, Son, & Co., 1892. Page 5.

- Loomis A.L. Evergreen forests as a therapeutic agent in Pulmonary Phthisis. Climatological Association Meeting 1887; 4:109-120.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 20.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 25.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L. page 53.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., pages 205-206.

- Lindberg D.A.B. and Howe S.E. “My Flying Machine was Out of Order.” Trans Amer. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2009; 120: 99-111.

- Warner J.H. The Therapeutic Perspective: Medical Practice, Knowledge, and Identity in America 1820-1885. Princeton University Press, Princeton N.J., 1997, page 258.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 183.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 82.

- Ibid., Ellison DL., page 112 ff.

- Ibid., Ellison DL., page 109 ff.

- Ibid., Ellison DL., page 128-131.

- Ibid., Ellison DL., pages 142-143.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 300-301.

- McCullough D. The Greater Journey: Americans in Paris. Simon and Schuster, 2011. Page 108.

- Ibid., McCullough D., page 114.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 313.

- Ibid., Ellison D.L., page 230.

- Ibid., Trudeau E.L., page 317.

GREGORY M. RUTECKI, MD, received his Medical Degree cum laude from the University of Illinois, Chicago (1974). He completed Internal Medicine training at the Ohio State University Medical Center (1977) and a Fellow-ship in Nephrology at the University of Minnesota (1980). After 12 years of Private Nephrology Practice, he re-entered Academic Medicine at The Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine (awarded “Master Teacher” designation) and became the E. Stephen Kurtides Chair of Medical Education at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and Professor of Medicine at the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University. He now practices Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2015 – Volume 7, Issue 4

Leave a Reply