Jorge Lazareff

Los Angeles, California, United States

I saw the painting at the warehouses at 50 Moganshan Road, which have been transformed into a sui-generis art district. The layout of the place allows for a chaotic meandering, from a wide space with art on the walls and solicitous employees standing by screen desktops, to a maze of small rooms where the paintings are laid against the wall and a man is feeding noodles to a kitty; and at the next turn you are back in an affluent gallery.

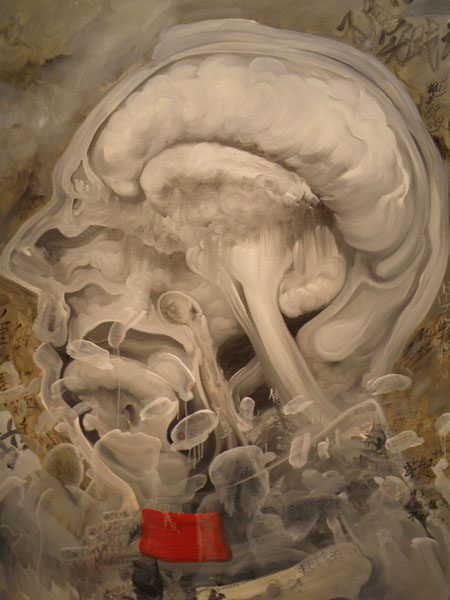

This painting was in such an unkempt room that I was allowed to photograph it with my digital camera, an anathema anywhere else on Moganshan Road. It shows the silhouette of a brain. In our imagination, the brain is distant from every other organ of the body, seated in its bony case wrapped by a membrane with the evocative name of dura mater. Francis Crick captures that perennial gestalt; “we. . .are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.”1

The artist disagrees with Crick. He has filled the brain with emotion and vigor. Anatomy is not hidden, and we identify the various parts of the brain stem, connected with streamlined strokes. The order of the neuroanatomy textbooks has been blurred: there are no more fictitious distinctions between the cranial nerves and the basal ganglia. Malcolm de Chazal anticipated in 1948 a perfect epigraph: “the cerebellum and the cerebrum are respectively our human Senate and House, where the body is the people. . .All social democracies originate in the body’s democracy and model themselves on it.”2

The red banner represents the people vertical to everything, like a shot spinning the innards of the brain into fat and alcohol. It stirs the chemistry of the liver, accelerates the heart rate, and readies the kidneys and other viscera to engage with the inputs and outputs from the hypothalamus or the cerebellar nuclei. The masses, which thrust into the head, provoke a storm that culminates in atomic fallout or heavy rain.

This subversive interpretation of the brain stands in opposition to that of Christian philosopher Nemesius in Syria (390 AD), to the phrenologists, to the researchers who work with functional MRI (fMRI), and to global health administrators who think the poor suffer only from infectious diseases. For the contemporary phrenologists, the brain-mind complex is a closed circuitry, composed of three elements (memory, reason, and imagination), or of thirty five, or as many as a contemporary researcher can justify on a grant application. In fMRI acquired brain maps, the attributes of the mind are plastered over the surface of the skull or sprinkled as red dots on the cerebral cortex. The scan resembles a subway map with the name of the stations but with no reference to what is outside on the streets. And what is happening on the streets is that poverty, stress, and malnutrition are modifying the anatomy of the brain, pruning dendrite spines and rendering men and women in poor countries, or in our own cities, with borderline cognitive abilities, numbed, and without the biological tools to find a way out.

Looking at this painting is like standing on a busy street in a metropolis, hearing the underground rumble and feeling the heat of the passing trains on the sole of your shoes. The painting screams that the brain is human. And what is wonderful about it is that the artist does not diminish the power of the brain by presenting it vulnerable and open. It is still wider than the sky, deeper than the sea, and similar to God as sound and syllable are.3

Shortly after my first sighting of the Chinese painting I taught an elective course to medical students: “The brain and its environment.” The idea that inspired my course was that medicine is a social science, hence clinical neurosciences are also social. As I intended to use the image in my lecture, I e-mailed the person whose card I took from the gallery and asked permission to display the image in my PowerPoint presentation. She answered some days later that the artist, Tian Mangzi, had agreed. I also inquired about its price, which while not excessive was beyond our means at the time.

In the following four years, my wife and I returned to Shanghai, and every time we explored the galleries on Moganshan Road searching for the painting. The galleries in the district morph and merge into new layouts, so every year the process was different. We meticulously focused on finding a place where a cat would be fed noodles by a man deep in thought.

In 2010 we thought we had found the gallery, but the painting was no longer there. When I inquired about it, I was told that the government had forbidden its display and that what we started calling “The brain” was the only work of Tian Mangzi that had been banned. Eventually, both the artist and the gallery wanted us to have the painting, so we bought it and shipped it to our house in Los Angeles.

What in that innocent painting of the dialectic brain could have bothered the censors? The sentences scattered around the head were party slogans from Mao’s time, nothing offensive. I later located on the Internet an article on Tian Mangzi,4 who at that time was painting apples. In this article: “Tian Mangzi’s Apples/Planets,” he expressed his disappointment and helplessness about the world after the Tiananmen Square massacre. So perhaps he and the censors saw in the painting an atomic fallout coming down from a mushroom-like corpus callosum. For me it is not atomic debris, but heavy rain falling from a stormy sky.

Every patient with a disease of the central nervous system is that brain. There is the disease with its biological roots, and there is the individual with his needs. But those needs are not polite and humble, and they have to be felt by the physicians like the Winter Palace felt the trembling of the masses storming in. These needs have the potential to destroy if unheard or to better everything. Listening and standing by the side of the crib will not pacify them; they demand attention much before we discover the disease. The functional recovery of a malnourished child is not the same as that of a child whose family is not stricken by poverty. You are not treating that spot just at the top of the white tracts bellow the frontal lobes, you are treating a swirl of molecules. So better pay attention to the red flag, “for the brain alone is not worthy of the muse.”5

References

- Crick Francis, The astonishing hypothesis: The scientific search for the soul. New York. Scribner (1993)

- de Chazal, Malcom. SeNs-PLAsTIQUe. Los Angeles. Green Integer. (2008) p. 37

- Dickinson, Emily. CXXVI. Complete poems. Boston. Scribner (1924)

- http://www.artforum.com.sg/artists_by_country/china/tianmangzi5.html

- Whitman, Walt. One self I sing. Poetry and Prose. The Library of America. New York (1982) p 165.

JORGE A. LAZAREFF, MD, was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1953. He received his medical degree from Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. He was a resident in Neurosurgery in Buenos Aires from 1979 to 1984 and a fellow at University of Cape Town from 1984 to 1986 and University of Alberta from 1986 to 1988. He was the Chair of the Department of Experimental Surgery and Neurosurgery at Hospital Infantil de Mexico from 1988 to 1993. He has been working at UCLA since 1993 and he is passionately committed to medicine as a social science and the development of pediatric neurology/neurosurgery in the developing world.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 1

Leave a Reply