Donatella Lippi

Florence, Italy

Luigi Padeletti

Florence, Italy

New York Academy of Medicine

The only unquestionably life-portrait of Vesalius’ is the wood-cut which finds its place in the frontispieces of both editions of the Fabrica1 in German and Latin editions of the Epitome,2 as well as in the 1546 Letter on the China Root.3 This portrait was done by Jan Stephan van Calcar (1499-1546), one of Titian’s pupils, and it can be considered the touchstone of all the subsequent Vesalius’ portraits.

Starting from this prototype, artists have sought to reproduce Vesalius’ features usually as those of a popular hero, according to their own emotional response and style.

Even if many of these portraits belong to the categories of fakes and frauds, the presence of Vesalius’ portrait in scientific books could provide a sort of guarantee of the correctness of the anatomical content, a sort of a seal of validity.

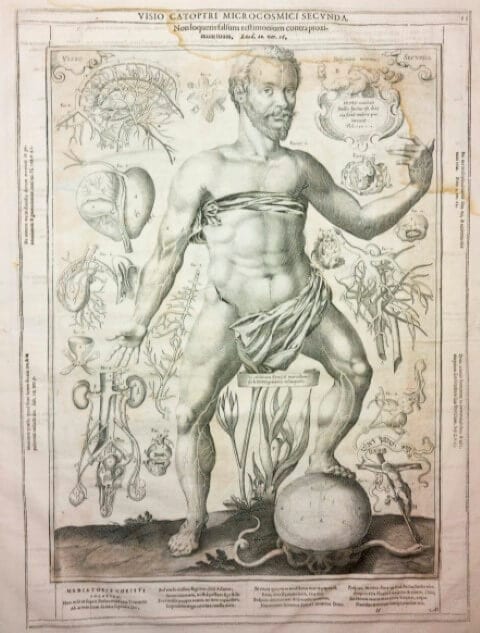

In 1613, for instance, the Augsburg engraver Lucas Kilian (1579–1637) produced a set of three broadsheets of human anatomy, which represent the most intricate early examples of interactive prints, known as “fugitive sheets” or “flap anatomies”: the use of these printed flaps began in the 16th century, and were primarily printed in Germany. It is thought that they were used by barbers and surgeons as reference guides: these publications invite the viewer to participate in virtual autopsies through the process of unfolding their movable leaves, simulating the act of human dissection.

Kilian’s work features three full-page plates with dozens of detailed anatomical illustrations superimposed so that lifting the layers shows the anatomy as it would appear during dissection: eight prints of the plates were produced then cut apart and pasted together to form the layers. While Kilian was the engraver of these broadsheets, the designer of the anatomical content was a medical doctor, Johann Remmelin (1583-1632).

The plates were printed in 1613, and the text without the plates was printed the following year, both without the consent of the author. The first authorized edition was printed in Latin in 1619 with the title Catoptrum Microcosmicum.4 These original plates seem to have fallen into the hands of a Veronese book-dealer who used them for speculation, asserting that he had obtained possession of the plates from the anatomist Piccolomini, and published them as a posthumous work of Piccolomini.5

The first of the three Kilian/Remmelin’s sheets (Visio prima) shows a male and a female figure, modelled after Albrecht Dϋrer’s 1504 Adam and Eve; the second and third vision show larger scale image of Adam and Eve, each standing on a skull with its own flaps.

Adam demonstrates the workings of the heart on the left-hand side: upon the naked body, the head of Vesalius, three-quarter view, is set. (Fig. 1)

Vesalius has a wide face, with a high open forehead and with emphasized protuberance of the frontal prominence and brows.

The thick-lipped mouth is bordered by a full moustache, horizontal in direction of its growth. The beard of medium length and thickness with sideburns, sweeping down to a point, is the typical Stiletto beard. The thickening of the right eyebrow conceals the small wart, which occurs in Calcar’s prototype.

Kilian’s engraving can be therefore considered an attempt to reproduce a copy of Calcar’s portrait of Vesalius in the Fabrica, with the same sly smiling expression: the reason of the occurrence of Vesalius’ features in Remmelin’s Catoptrum is therefore, at the same time, Remmelin’s captatio benevolentiae (striving for benevolence), the proof of Vesalius’ popularity and a tribute of devote appreciation to the Father of Anatomy itself.

References

- Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, scholae medicorum Patavinae professoris, de Humani corporis fabrica Libri septem, Basileae: [ex officinal Ioannis Oporini], [Anno salutis reparatae 1543]

- Andreae Vesalii…suorum de humani corporis fabrica epitome. Basileae: ex officina J. Oporinus, 1543.

- Andreae Vesalii Bruxellensis, medici Caesarei, Epistola, rationem modumque propinandi radicis Chymae decocti …Venetiis: Comin da Trino, 1546.

- Archangeli Piccolomini Anatome integra, revisa, tabulis explanata et iconibus mirificam humani corporis fabricam, ad ipsum naturae archetypum exprimentibus, cum praefatione et emendatione Joann. Fantoni, Veronae, sumptib. Gabrielis Julii de Ferrariis, 1754, fol.

- Remmelin Johann (1583-1632), Catoptrum microcosmicum, suis aere incisis vistionibus splendens, cum historia & pinace, de nouo prodit. Augustae Vindelicorum [Augsburg]: Typis Dauidis Francki, 1619.

DONATELLA LIPPI, PhD, is a professor of the history of medicine and a scholar of Classics whose focus is the history of medicine, archaeology, archivistics, and bioethics. A visiting professor at many foreign universities, she is the Vice-President of the Italian Society for the History of Medicine. She is also author of more than 300 scientific publications, many of which have been published in international journals. She is the president of the Centre of Medical Humanities of the University of Florence.

LUIGI PADELETTI, MD, is a full professor of cardiology, Director of the Postgraduate School of Cardiology at the University of Florence (Italy), and the president of the Italian Heart Rhythm Society.

Leave a Reply