George Dunea

Chicago, Illinois, United States

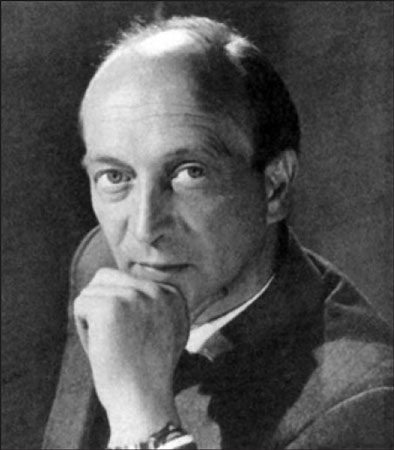

Dr. Paul Wood, the greatest British cardiologist of his time, died in London on July 13, 1962—half a century ago.1 Born in 1907, he went to school in Australia, took his internship in New Zealand, and after a stint as cardiologist in London, served with distinction in World War II. He spent the greater part of his academic life in London, where he performed his first cardiac catheterization in 1947. His major contribution was to refine the bedside diagnosis of heart disease, correlating the clinical findings with the chest X-ray, the electrocardiogram, and the hemodynamic data obtained by cardiac catheterization. He was the first truly modern cardiologist; his early clinical papers became classics, and his influence on his generation was enormous.1–4 Now, half a century later, new articles still appear about him, written by colleagues or trainees under such titles as “The Master’s Legacy” in 1998 and “Icons in Cardiology” in 2004, with a more recent article by professor Celia Oakley in 2010.2,4,5

Paul Wood wrote the first draft of his textbook on the heart and circulation at the end of the war, but the manuscript was lost, and he had to rewrite it in its entirety. When published in 1950, it quickly became the bible of cardiology; so highly desired, when it went out of print, cardiologists were desperate to get hold of a copy. It emphasized that clinicians were expected to make a preliminary diagnosis from a detailed clinical examination of the heart, with subsequent confirmation by ancillary tests.

In the early 1960s postgraduate doctors from many countries of the world flocked to London to attend his clinical demonstrations at the National Heart Hospital. Armed with little notebooks, they would cryptically write down clinical pearls such as “second heart sound increase in inspiratory,” then laying on hands and stethoscopes before presenting their findings.

These were the days of paternalism, when doctors did not upset patients with bad news (sometimes not even telling them their blood pressure). The word “cancer” was never to be mentioned except as a “lump” in the chest or in the stomach. Paul Wood was an impressive teacher, but not always tolerant. On one occasion, when a young physician examining the patient said that the heart was enlarged, he snapped: “Would you like to have an enlarged heart?”

“No, sir,” replied the abashed young physician.

“Then do not say it in front of the patient,” came the indignant repartee.

These were also the early days of antihypertensive therapy; potent drugs were yet to come, and much reliance was placed on low-sodium diets. So one day Paul Wood presented a hypertensive patient and asked him to tell the audience how he managed his diet. The man went into great detail to explain his strategy—how he made his entire family cut out salt and how salt-free diets had become a mission with him. When going to a restaurant he would make a fuss, the patient continued, asking for the manager, proudly announcing that he was on low-salt diet and insisting that all the delicacies of the house be served salt-free. After the patient left, Paul Wood asked the students what they had learned from this case. They gave various answers such as the diet worked, or it needed perseverance. All wrong, he said, declaring that patients likely to stick to a low-salt diet were overly compulsive, meticulous, arrogant, and often insufferable.

Unlike other influential physicians of his time, Paul Wood was a great believer in the use of anticoagulants for ischemic heart disease. In this he differed from other cardiologists, such as William Evans, who made his students promise never to give potassium or rat poison (warfarin) to their patients. Evans, interestingly enough, also required his students to promise in writing that they would extensively gaze at the neck veins—to learn to distinguish the “flick” of the a wave from the “surge” of the v wave.

When Paul Wood died in 1962, it was rumored that he had injected himself with heparin for a non-coronary condition (such as lupus pericarditis) and died from cardiac tamponade. In fact he succumbed to an occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery.2 He had said he did not want to be resuscitated, and physicians respected his wish. In 1962 the accepted approach would have been to open the chest with a knife and perform direct cardiac massage. Perhaps an electrical jolt to the chest might have saved his life, but that was a long time before intensive care and coronary units.

Notes

- “Obituary: Paul Wood, OBE, MD, FRCP,” BMJ (July 1962): 262.

- J. Somerville, “The Master’s Legacy: the First Paul Wood Lecture,” Heart 80 (1998): 612.

- J. Bauer, “Wood, Paul Hamilton (1907–1962),” Heart Lung & Circulation 12, no. S3 (October 2003).

- Arnold M. Katz, “Icons of Cardiology: Paul Hamilton Wood: Clinician—Scientist,” Dialogues in Cardiovascular Medicine 9 (2004):117.

- C. Oakley, “Historic Moments in Cardiology,” Circulation 26, no. f13 (January 2010).

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, FACP, FRCP, FASN is the president and CEO of the Hektoen Institute of Medicine. He is also a professor of medicine at University of Illinois at Chicago, the medical director of Chicago Dialysis Center, and founding chairman emeritus, Division of Nephrology, Stroger Hospital of Cook County. He also serves as Editor-in-Chief of Hektoen International.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 4, Issue 2 – Spring 2012 and Volume 5, Issue 2 – Spring 2013

Leave a Reply