Faraze A. Niazi

Jack E. Riggs

Morgantown, West Virginia, United States

A belief is not merely an idea the mind possesses; it is an idea that possesses the mind.

-Robert Oxton Bolton

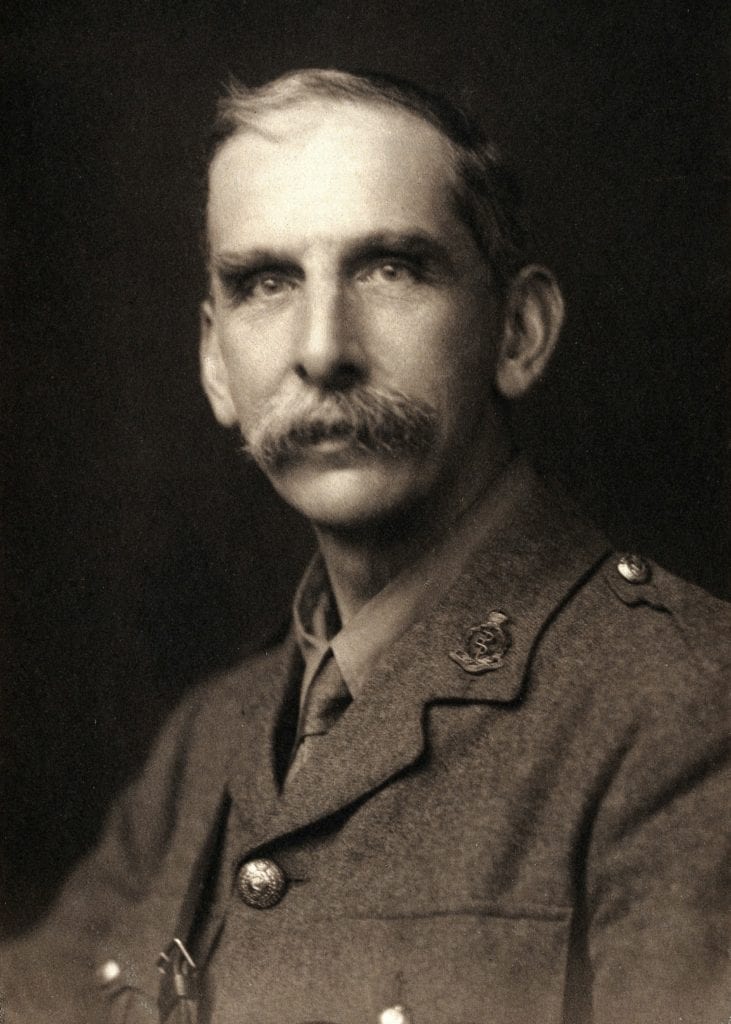

Sir Victor Horsley is generally regarded as the “Father of Neurosurgery.”1 He may have even been destined for greatness, as it was Queen Victoria herself who suggested his first name.2 Among his many deserved claims to fame is the first successful treatment of epilepsy when in 1886 he removed an area of trauma-induced cortical scar tissue.1,3 In 1887 he was the first to remove a benign cervical spinal cord tumor and reverse the patient’s paraplegia.1 He was also the first to attempt to remove a pinealoma, to expose the pituitary gland, and to perform a root section to alleviate the pain of trigeminal neuralgia.4-6

Horsley also made several non-neurosurgical contributions to medicine. He researched the relationship between the thyroid gland, myxedema, and cretinism, and he played an important role in curtailing the spread of rabies by vaccinating and quarantining dogs brought into the United Kingdom.2

Despite his many medical accomplishments, Horsley’s passions evoked criticism and produced enemies. He strongly supported animal experimentation, which made him a target of anti-vivisection groups.1 He was also a staunch advocate for women’s suffrage.2

Though hardly a pacifist, Horsley expressed his opinion of war quite clearly. He saw “this stupid, insane folly of war (pg. 285) . . . a madness to be cured by democracy and universal suffrage (pg. 286) . . . What too is irritating is that, as of course we shall win ultimately, it is certain that the lives sacrificed will be wholly forgotten in a year or two, except by the poor relatives of those thousands who have died for absolutely nothing” (pg. 305).7

The irony of Horsley’s words is that he would himself die while serving with the British army during World War I in present-day Iraq.8-9 Indeed, when asked as a child what he wanted to be when he grew up, Horsley proclaimed “a cavalry officer” (pg. 11).7 Horsley often maintained an association with the military and even maneuvered to obtain an active duty commission with the British army in World War I at a relatively old age. He seems to have done this to express his displeasure with the medical care provided to British soldiers. “The public-house loafer at home is far better treated by the nation medically than the soldier who is sacrificing his life” (pg. 300).7 Horsley had two sons, both severely wounded in that war. “Thank goodness the boys are in France (pg. 295) . . . My eldest son Siwald, who was wounded at Neuve Chapelle, has been invalided (pg. 304) . . . The second, Oswald, who was shot in the left shoulder in 1914, was hit in the right shoulder last August” (pg. 305).7 Accordingly, he was willing to provide such care to British soldiers himself.8

Developing a strong aversion to alcohol during his college days, Horsley made an unsuccessful bid for a seat in Parliament on a temperance platform.1,9-10 He co-authored a monograph entitled Alcohol and the Human Body which was described as “deeply biased” and “unusual” with “naïve statistics and tenuous physiological inferences.”9 “Not only did Horsley castigate drinkers, but he consistently used his own health as an example of the benefits of abstinence.”9 There is nothing inherently wrong with being passionate about the harmful effects of alcohol unless you confuse your own abstinence as providing some unfounded biological immunity. His words in letters to his wife confirmed and validated those assertions; “Mind you, I like the heat and feel extremely well with it (pg 298) . . . Real swelter, last two days: 108-110 in shade (pg. 324) . . . I am perfectly fit. Of course it’s no end hot (pg. 327) . . . We are all very fit here, those who are teetotalers . . . Of course in the sun it is 150° and over (pg.331).”7

Horsley passionately believed in abstinence, and also believed that his abstinence conferred upon him some protection against heat injury. But he died from heatstroke on July 16, 1916. In the end, passion, no matter the depth of conviction, does not trump biology. In Horsley’s obituary, published in the British Medical Journal on July 29, 1916, Sir William Osler commented, “What demon drove a man of this type into the muddy pool of politics? A born reformer, he could not resist. Fearless, dogmatic, and assertive, once in a contest no manna-dropping words came from his tongue. A hard hitter, and always with a fanatical conviction of the justice of his cause, what wonder that the world’s coarse thumb and finger could not always plumb the sincerity of his motives!”11

Commenting in the same obituary as Osler, Sir R. Havelock Charles said it even more frankly, “It was unwise for a man of his age, who had had no experience of tropical heat, usages, or habits, to have gone to work in the confines of the Persian Gulf. He should not have been there. His life has been thrown away. That is the sadness of his death.”11

It is tragically ironic that Sir Victor Horsley, a giant in medicine and believer in the utility of science, should fall victim to unscientific beliefs that created in his mind a giant fatal blind spot.

References

- Lyons JB. Sir Victor Horsley. Med Hist 1967;11:361-73.

- MacNalty A. Sir Victor Horsley: his life and work. Br Med J 1957;1(5024):910-6.

- Taylor DC. One hundred years of epilepsy surgery: Sir Victor Horsley’s contribution. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1986;49:485-8.

- Jefferson G. Sir Victor Horsley, 1857-1916, centenary lecture. Br Med J 1957;1(5024):903-10.

- Tan T-C, Black PM. Sir Victor Horsley (1857-1916): pioneer of neurological surgery. Neurosurgery 2002;50:607-12.

- Powell MP. Sir Victor Horsley at the birth of neurosurgery. Brain 2016;139:631-4.

- Paget S. Sir Victor Horsley, a study of his life and work. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1920.

- Riggs JE, Riggs AJ. Prominent 59-year-old British neurosurgeon, Victor Horsley, succumbs to heatstroke while serving with Allied troops in Iraq. Br J Neurosurg 2004;18:375-6.

- Hanigan WC. Obstinate valour: the military service and death of Sir Victor Horsley. Br J Neurosurg 1994;8:279-88.

- Dunnill MS. Victor Horsley (1857-1916) and the temperance movement. J Med Biogr 2012;20:25-31.

- Obituary, Sir Victor Horsley. Brit Med J 1916;2:162-7.

FARAZE A. NIAZI, MD, is a neurology resident at West Virginia University. She is interested in neurocritical care, ethics, and Middle East studies.

JACK E. RIGGS, MD, is a professor of neurology at West Virginia University.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 1 – Winter 2021

Leave a Reply