The decline and fall of the over one-thousand-year-old Byzantine empire constitutes an epic tragedy. Year after year, decade after decade, this once great empire became weaker and less likely to survive. In 1204, the Crusaders and Venetians conquered and plundered its capital, Constantinople, and divided the empire into four kingdoms. A newly established Latin empire received one-quarter of all the territories, the rest going to Venice and to the Greek successor states of Nicaea, Trebizond, and Epirus. But the Latin empire lasted only until 1270 when the Empire of Nicaea under Michael Palaeologus VIII reconquered Constantinople and re-established the Byzantine Empire.

Michael Palaeologus was a competent ruler, but his successors were not necessarily so, and they were constantly embroiled in conflicts with the Turks, Serbians, and Bulgars. Michael was succeeded in 1282 by his son, Andronicus II, “a feeble and incompetent ruler” who, however, lived to the age of 73 and reigned for almost half a century. Even before the death of his own son, Michael IX, in 1320, Andronicus II had bestowed the rank of co-emperor on his nineteen-year-old grandson, the future Andronicus III.1,2

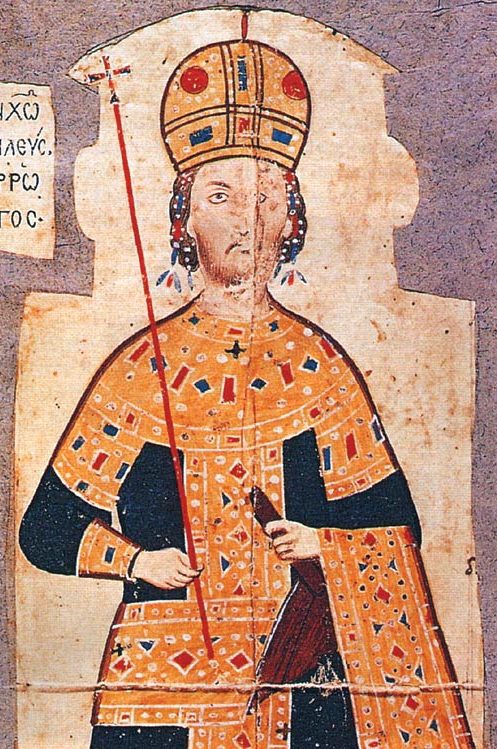

Born in 1297, Andronicus III was an intelligent and outstandingly good-looking young man. He had once been the favorite of his austere grandfather, but began to try his patience by drinking, gambling, carousing, and running up high debts, causing him to exclude him from the succession. A civil war ensued after 1320, and in 1328 Andronicus III invaded Constantinople and forced his grandfather to abdicate.1,2

Andronicus III Palaeologus ruled over Byzantium from 1328 to 1341. He made administrative and military reforms and recaptured some lost territories in the Balkans, but later lost control over others. For all the waywardness of his early youth, he matured into an energetic, hardworking, and conscientious emperor, ruling wisely and well, better than that grandfather who had tried to keep him off the throne. He achieved some successes, regaining Thessaly and Epirus, but eventually lost Nicaea and most of Asia Minor to the Turks.1,2

Already in 1321 Andronicus was reported to have been ill for forty days with a fever. He had nose bleeds, and fevers recurred for the next eleven months, after which he partially recovered. But further attacks occurred over the next two decades. His spleen became massively enlarged, reaching to the umbilicus and even lower. Though attended by Greek and even Turkish physicians, his condition gradually worsened. Eventually, he fell into a coma and died on June 15, 1341, at the age of forty-five. Lascaratos and Marketos have stressed the difficulty of making a diagnosis from medieval medical literature. But they believe he suffered from chronic malaria from a mixed infection by several species of Plasmodium, leading to a state that has been referred to as malarial cachexia.3

Indeed, malaria in the Byzantine Empire had been rampant during most of the latter’s existence, especially in coastal and marshy regions conducive to mosquito breeding. Treatment was unavailing, and so was prevention, especially as it was not known that the disease was spread by mosquitoes. Malaria afflicted all social classes, affecting agricultural productivity, weakening the population, and disrupting military campaigns. It undoubtedly played an important role in the declining fortunes of Andronicus III and his empire.

References

- George Ostrogorsky. History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- John Julius Norwich. Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. New York: Alfred A. Knoff; 1995.

- J. Lascararos and S. Marketos. The fatal disease of the Byzantine Emperor Andronicus. J Roy Soc Med Feb 1991;90:106.

Leave a Reply