Jayant Radhakrishnan

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Pierre-Fidèle Bretonneau described diphtheria as a distinct entity in 1821.1 He named it after the Greek word for leather2 because of the thick gray membrane that forms in the throat. Physicians before him, starting with Hippocrates, considered asphyxiating diseases as a group that also included tonsillitis, croup, and malignant angina. Mercado and Villareal referred to “El garotillo” (strangulation).3

Edwin Klebs identified the etiologic agent in 1883 and Friedrich August Johannes Löffler cultured it from the back of the throat. Corynebacterium diphtheriae was initially named the Klebs-Löffler bacterium.1 In 1890, Emile von Behring, Erich Wernicke, and Kitasato Shibasaburō developed the first agents effective against diphtheria and tetanus. When they injected laboratory animals with attenuated infectious agents, the serum produced in response protected, nonimmunized animals from a virulent form of the same organisms. However, only Behring was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1901.4 Behring’s first trials of serum therapy in humans with diphtheria failed. Paul Ehrlich, Emile Roux, and Alexandre Yersin deserve credit for successful serum treatment in humans. Using their techniques, Behring achieved a 77% cure rate in 220 children suffering from diphtheria in 1894. Serum injected within the first two days after diagnosis was nearly 100% curative. The cure rate dropped to 50% if injection was delayed to six days. This indicates that the antitoxin worked on circulating exotoxins but not on exotoxins adherent to the target cells.5 By 1913, Behring developed a vaccine named diphtheria AT by creating complexes of toxin and antitoxin.5

Paul Ehrlich enriched serum to obtain therapeutic concentrations of antitoxins. He also developed a protocol to standardize its quantity and quality.5 To obtain large volumes of serum, Behring and Ehrlich first used a sheep discarded by Robert Koch, while Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin used horses. In 1888, Roux and Yersin reduced diphtheria fatality from 50.7% to 24.5%. Behring also switched to horses as the serum of other large animals was not concentrated enough. He obtained horses due to be slaughtered. After a four-week quarantine, they were inoculated with three successively increasing toxin doses. When inoculated they lost their appetite, developed fever and breathing difficulties, and at times went into shock. When blood samples demonstrated that maximal antitoxin levels had been reached, five liters of blood (1/10 of the total blood volume) were withdrawn. The horses then had three to four weeks to recover. During this period, they were extremely weak and prone to infections. The cycle of injections and blood draws continued as long as possible. As scientists gained experience, they began reintroducing the red cells back into the animal, and plasmapheresis was born.

In the late nineteenth century, substantial amounts of antitoxin were needed, as diphtheria was widespread. Scientists in the United States went to work. By the end of December 1894, large-scale production was in full swing, and antitoxin was successfully used throughout the country.6

Jim had the job of supplying antitoxin for St. Louis, Missouri. He was a retired milk-wagon horse who produced large amounts of highly effective antitoxin. However, in October of 1901, three children from one family—six, four, and two years old—died from tetanus after receiving the antitoxin. A few days later, Jim also died of tetanus. The inquest determined that the city bacteriologist, Armand Ravold, did not immunize Jim against tetanus and had also neglected to test the antitoxin on guinea pigs before approving it for human use. He was dismissed. Sadly, an African-American janitor, Henry Taylor, whose only involvement was that of carrying unlabeled flasks of the serum to assistant bacteriologist Martin Schmidt, was also fired. The commission asserted that he obstructed the investigation by giving contradictory testimonies.6

It was later learned that twelve other children had also died from this contaminated serum. Consequently, the Biologic Products Act, or the Virus-Toxin Law, was passed in 1902. The act was to be enforced by the Hygienic Laboratory of the Marine Hospital Service, renamed the National Institutes of Health in 1930.7 The 28.5 liters (7.5 US gallons) of antitoxin Jim produced saved many lives. The laws enacted because of him are still saving lives more than a century later.

The antitoxin became available in the early 1900s, but it still had to be distributed to populations at risk, even in hard-to-reach locations such as Nome, Alaska. Nome is 2° south of the Arctic Circle on the Norton Sound of the Bering Sea. Inuit people have lived there for 10,000 years in a settlement known as Sitnasuak. In 1900, the chief cartographer of the British Admiralty stated that the town was renamed Nome because of bad handwriting. A draftsman on the H.M.S. Herald (1850–1852) apparently misread the question “? Name” as “C Nome” (C for Cape) on a chart. The US Government seems to agree.8 Nome had no road or rail connections with interior Alaska. From about November to May, the temperatures hovered around -10 to -55° F, and the Bering Sea froze.

In the summer of 1924, Dr. Curtis Welch realized that the 8,000 units of diphtheria antitoxin in Nome had expired. He ordered serum from Juneau, but it did not arrive before Nome was frozen in. By January 1925, he realized that what he initially diagnosed as tonsillitis was actually diphtheria. One child died when he hesitated to use the expired serum. He used it on a second child who also died. It was apparent that an epidemic was in the making. Based on experience with the influenza pandemic of 1918–1920, he knew that children and the entire native population in surrounding areas would be decimated. He sent telegrams to all the towns in Alaska, the governor of the territory, and even to the US Public Health Service in Washington asking for one million units of antitoxin.9

The following is a brief summary of a vivid account by Gay and Laney Salisbury, of the heroic efforts of twenty mushers and about 150 dogs that carried the serum to Nome under the harshest of conditions.10 300,000 units of serum were found in Anchorage, but Governor Scott Cordelle Bone still had to transport it 1,000 miles up to Nome.One choice was to use airplanes. In February 1924, mail had been delivered for the first time by air between Fairbanks and McGrath, a distance of about 270 miles. However, air travel in winter with water-cooled aircraft engines in open cockpits was fraught with risks for pilots. Furthermore, the planes had already been stripped down for the winter. The governor decided against planes. He was proven right two weeks later when an attempt to send a second batch of antitoxin by air failed. They could not get the plane off the ground, despite valiant efforts over three days. A second dog run carried that serum to Nome.

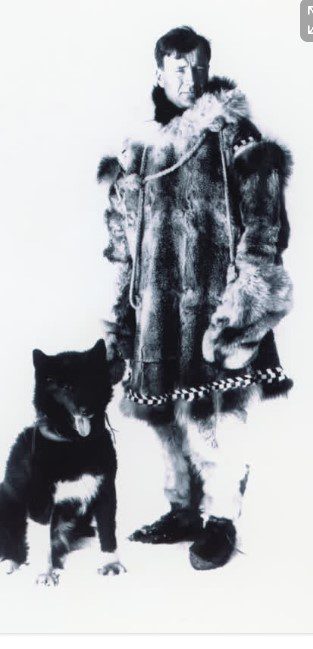

There was a rail line from Anchorage to Nenana, which is 674 miles from Nome. The superintendent of the territorial Board of Health suggested carrying the antitoxin to Nenana by train. Then one fast dog team would go west from Nenana with the serum, and Leonhard Seppala with his twelve-year-old lead dog Togo, the fastest dog team in Alaska, would meet the first team about halfway, in Nulato, and run the serum back to Nome. The governor felt it would be faster to have a relay of dog teams to eliminate rest periods. The best mushers were Athabaskan mail carriers, so the governor had the US Post Office Inspector assemble a group of his finest. They were assigned to wait at designated roadhouses along the way to carry the parcel onwards without a break.

At Nenana the conductor handed the antitoxin to “Wild Bill” Shannon. On January 27 at 9 PM, he left with the package. Temperatures were as low as -62° F and the wind blew at 25 miles per hour. His lead dog, Blackie, avoided treacherous trail conditions and brought him into Tolovana, fifty-two miles away, hypothermic and frost bitten. Three dogs he dropped off earlier in Minto, as well as possibly a fourth, died of hypothermia. When the second musher, Edgar Kallands, reached Manley Hot Springs, it is said that the owner of the roadhouse poured boiling water over his hands to pry them off the handlebar of the sled. The relay continued, and mushers suffered through storms, extreme cold, whiteout conditions, and dogs’ deaths on the way. Charlie Evans, the twelfth leg, came into Nulato pulling his sled on foot with his two dead lead dogs in the basket. The seventeenth musher, Henry Ivanoff, handed the serum to Seppala near Shaktoolik. Despite a temperature of -70° F and whiteout conditions, Togo and Seppala had come over the treacherous, unprotected, windy ice floes of Norton Sound to receive the serum. They turned back immediately and again crossed the sound to Golovin and handed it to Charlie Olson. Olson went through a storm to Bluff where he handed it over to Gunnar Kaasen, who was told to wait for the storm to abate. Two hours later, Kaasen had enough, and he drove into the storm. His lead dog, Balto, also belonged to Seppala. At Solomon the strong winds overturned Kaasen’s sled and the serum. He got frostbite digging around in the snow with bare hands to find the serum. The musher was asleep at the next relay point, so Kaasen continued on. Balto brought him into Nome by 5:30 AM on February 2 to great fanfare.

Seppala was bothered that Balto received most of the acclaim. He felt that Togo’s magnificent run of 261 miles, compared to Balto’s fifty-three, made him the hero. However, the inexperienced Balto deserves plenty of credit for finding the way to Nome entirely on his own since a blinded Kaasen lost his bearings at Solomon. Balto went through snow drifts and avoided gaps in the broken ice of the Topkok River under whiteout conditions.

After the hue and cry died down, Balto and his teammates became part of a side show and lived in terrible conditions in California. Fortunately, George Kimble saw their atrocious conditions and publicized it. Children in Cleveland, Ohio raised enough money to buy the entire team. The dogs spent the rest of their lives in comfort at the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo. Balto now stands at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Togo stayed with Seppala and participated in many races and a breeding program. He is now at the Iditarod Trail Headquarters Museum in Wasilla, Alaska.

Two thirds of the 674 miles were covered by native mushers who have since largely been ignored. When asked why he volunteered, Edgar Nollner of Galena told the Associated Press in 1995, “I just wanted to help. That’s all.”

Bibliography

- What is the history of Diphtheria in America and other countries? National Vaccine Information Center (NVIC) https://www.nvic.org/disease-vaccine/diphtheria/history. Accessed January 27, 2024.

- Etymologia: Diphtheria. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013;19(11):1838. doi:10.3201/eid1911.et1911. Accessed January 28, 2024.

- Laval E. El garotillo [Difteria] en España [Siglos XVI y XVII] (2006). Revista chilena de infectología 23 (1): 78-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0716-10182006000100012.

- Emil von Behring: The Founder of Serum Therapy. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1901/behring/article/

- Kaufmann SHE (2017). Remembering Emil von Behring: from tetanus treatment to antibody cooperation with phagocytes. mBio 8:e00117-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00117-17.

- Richter C, Emrich J (October 2021). Hero horses in the fight against disease. J Immunol. The American Association of Immunologists. https://www.aai.org/About/History/History-Articles-Keep-for-Hierarchy/Hero-Horses-in-the-Fight-Against-Disease. Accessed January 30, 2024.

- Parascandola J. (November–December 1995). The Public Health Service and the Control of Biologics. Public Health Reports. 110(6):774-5. PMC 1381822. PMID 8570833.

- Orth DJ (1967). Dictionary of Alaska Place Names. Government Printing Office. https://doi.org/10.3133/pp567.

- Houdek J. The Serum Run of 1925. University of Alaska Anchorage. http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=Digital-Archives&page=Land-Sea-Air&cat=Dog-Mushing&viewpost=2&ContentId=2559. Accessed January 22, 2024.

- Salisbury G, Salisbury L (2003). The cruelest miles: The heroic story of dogs and men in a race against the epidemic. New York. W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-01962-4.

JAYANT RADHAKRISHNAN, MB, BS, MS (Surg), FACS, FAAP, completed a Pediatric Urology Fellowship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, following a Surgery Residency and Fellowship in Pediatric Surgery at the Cook County Hospital. He returned to the County Hospital and worked as an attending pediatric surgeon and served as the Chief of Pediatric Urology. Later he worked at the University of Illinois, Chicago, from where he retired as Professor of Surgery & Urology, and the Chief of Pediatric Surgery & Pediatric Urology. He has been an Emeritus Professor of Surgery and Urology at the University of Illinois since 2000.

Leave a Reply