When in April 1820 five members of a radical group plotted to murder the British Prime Minister Lord Liverpool, they were sentenced to be hanged as well as publicly decapitated and dissected. An unknown man wearing a mask appeared in the square and carried out the task with such speed and dexterity that people thought he must surely be a surgeon or a medical student. It turned out that the skilled man was an anatomy dissecting-room attendant, but this did not become known until much later. At the time and for unknown reasons, the suspicion fell on Dr. Thomas Wakley. In August, a man knocked at the door of his house. He was delivering a message, he said, and was thirsty; could he have a glass of water?

While Wakley went to fetch the water, the supposed messenger opened the door and let in his accomplices set for revenge. They stabbed Wakley, beat him up with clubs, and set his house on fire. As he had increased his insurance a few days before the incident, he was at first suspected to have been his own arsonist, with the insurance company refusing to pay him for the damage to his house, but eventually he won his case in court.

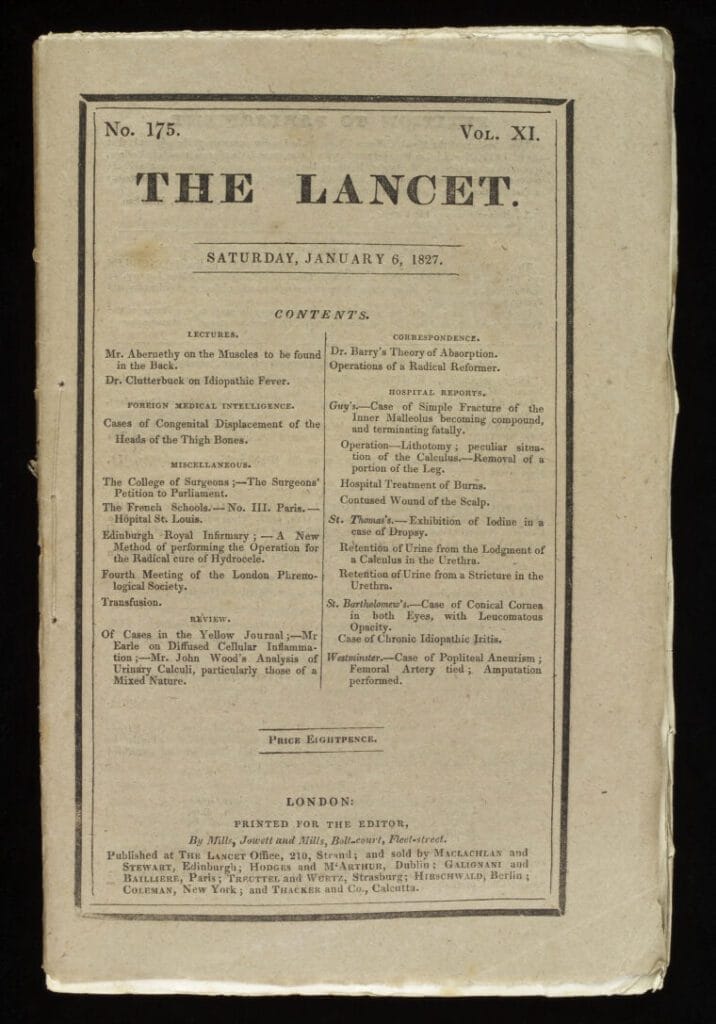

Thomas Wakley was the youngest of eleven children of a Devonshire farmer. He had studied medicine at Guy’s–Thomas’ for five years and in 1820 had opened a practice in central London, which however was largely ruined by the above-described events. In 1823, under the influence of a radical politician, he started an educational medical journal called The Lancet.1,2 He entered Parliament in 1835, and for some time also worked as a medical examiner (coroner) but spent most of his life as editor of his journal.

The journal was to educate doctors but also to expose what he perceived as the corruption, nepotism, and incompetence of some of the doctors, including several famous and powerful ones, at the medical schools. The educational function of the journal was at first fulfilled by reprinting the lectures given to paying students by the prominent London teaching hospital doctors. The prestigious Sir Astley Cooper good naturedly assented to this, but others battled him in the courts, accusing him of plagiarism for copying their lectures and syllabuses without their permission.3‑6 Wakely reveled in controversy and was involved in numerous court cases, not hesitating to attack in unmeasured terms the very heads of the profession as well as their medical societies. During his long career, he opposed the still-prevalent practice of vigorously purging and bleeding sick patients. He campaigned against flogging as a punishment and against the adulteration of foods. Advocating for the working man, he opposed restricted shopping hours, and insisted that museums and zoos should be open on Sundays.

Wakley died in Madeira in 1862 from probable tuberculosis and pulmonary hemorrhage occasioned by falling from a horse. He was succeeded by his son, and other members of his family continued to edit the journal for the next ninety years. On 5 October 2023 the Lancet celebrated its 200th birthday. It ranks today as one of the most prestigious and highly respected medical journals in the world. It also became the forerunner of what is now called evidence-based medical practice.

References

- Roger Jones. Thomas Wakley, plagiarism, libel, and the founding of the Lancet. Lancet 26 April 2008;373:1410.

- W.H. Macmenemey. The Lancet (1823-1973). British Medical Journal 29 Sept 1973;2:680.

- Editorial. Thomas Wakley,1795-1862: Editorial, British Medical Journal 26 May 1962:1462.

- Nova et Vetera. Thomas Wakley and the “Lancet”. British Medical Journal 6 Oct 1923:615.

- Sir Astley Cooper, in Hektoen International, Fall 2018.

- John Abernethy, in Hektoen International, Winter 2022.

4 responses

I enjoy this journal on line very mcy,

Did you once edit another journal my late father in Chicago received? Cannot recall name, but even as a young boy I enjoyed reading it.

Thank you for your kind words! Our Editor-in-Chief previously wrote extensively for the British Medical Journal in his columns Letters from Chicago and Soundings. Do you remember the content of the journal or the years it was published?

Thank you for providing this remarkable history of the founding of the Lancet.

very informative and entertaining.