Stephen Martin

Thailand

The British architecture of Kolkata, though by no means representative of modern India, has some extraordinary beauty. One of many outstanding sites is St. John’s Church, consecrated in 1787 (Fig 1) and based on James Gibbs’ St. Martin in the Fields in Trafalgar Square, London.

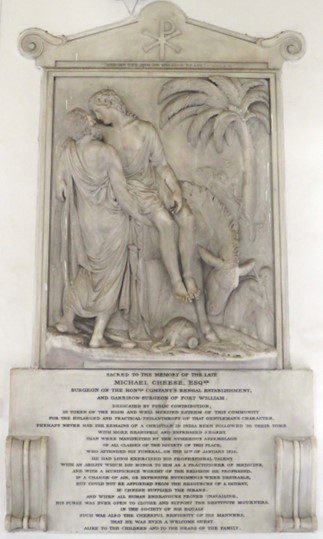

In the Regency period, Michael Cheese was the Company surgeon of what was then Calcutta, and garrison surgeon of Fort William, the city’s East India Company military base. He left for India as an assistant surgeon in 1792 and was promoted to surgeon in 1806, working in the senior post for ten years. Calcutta was the British administrative capital until 1912. Mr. Cheese’s monument is inside the church on the wall of the south aisle. It was paid for by the people of Calcutta and carved in London by the sculptor Richard Westmacott.

The main inscription reads:

In token of the high and well-merited esteem of this community for the enlarged and practical philanthropy of that gentleman’s character. Perhaps never had the remains of a Christian in India been followed to their tomb, with more heartfelt and expressed regret than were manifested by the numerous assemblage of all classes of the society of this place, who attended his funeral on the 15th of January 1816. He had long exercised his professional talent with an ability which did honour to him as a practitioner of medicine, and with a munificence worthy of the religion he professed.

If a change of air, or expensive nutriments were desirable, but could not be afforded from the resources of a patient, MR Cheese supplied the means: and when all human endeavours proved unavailing, his purse was ever open to clothe and support the destitute mourners. In the society of his equals such was also the cheerful benignity of his manners, that he was ever a welcome guest, alike to the children and to the heads of the family.

“All classes” could just refer to different ranks of soldiers, civil servants, teachers, merchants, and their families. However, records reveal that European town surgeons in Asia from the 1760s to the 1820s treated patients of all creeds and races. Cheese almost certainly did so too, considering the known practices and his character. The reference to respiratory and wasting diseases would have included a lot of tuberculosis. He did self-funded social work. Socializing between families was strong, compensating for social limitations.

The large monument (Fig 2) is in fine, unblemished, monochrome marble, with scrolled corbels on either side of the inscription that do not touch anything for support. The implication is that they support the intellectual weight of the text. The pediment at the top draws on a late Roman sarcophagus with a Chi Rho monogram, and also echoes French Empire style drawn from Egypt with a central moon-shaped (lunular) apex and scrolls in the eaves. Despite the trade wars between Anglo-Indian and Franco-Indian alliances and the Napoleonic military defeat, the French continued trading by agreement at Chandernagore, a little upstream in the Ganges Delta. Their headquarters remained at Pondicherry in the south. The British loathed Napoleon, but his taste in Egyptian art really caught on.

The frieze sculpture is impressive, the figures in a surprisingly full-size deep relief. Photography does not do it justice. Inscribed above the Good Samaritan: “And he set him on his own beast. Luke X 3.” The late Regency time of lavish sculpture shipped from London to Calcutta was also the start of a publishing expansion, though too late to tell us much more about Mr. Cheese. He died on 14 January 1816 at age fifty-eight after “a short illness.” His friends John and Elizabeth Dacruz also erected a headstone for his grave in north Park Street Burial Ground “in testimony of their respect and esteem for him.”

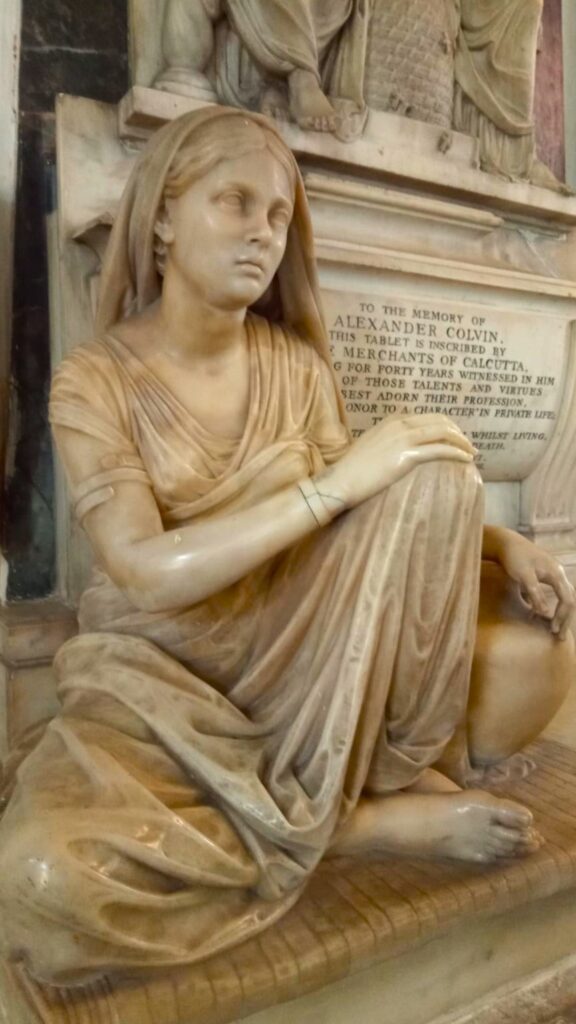

Two years later, Westmacott carved another world-class sculpture for St. John’s on the monument of the merchant Alexander Colvin. It depicts both crucial sustenance and integration. For this, Westmacott made a life-size whole-figure statue of a seated Indian girl with a water jar. (Fig 3) Above it is a beehive. The two together are emblems of food and drink and also echo the land of milk and honey.The sculpture is exquisite and of the utmost sensitivity. Those qualities resemble his liberated black slave on the tomb of Charles James Fox in Westminster Abbey. From his work, it is easy to read Westmacott’s values that stoked the humanitarianism for which he was later knighted.

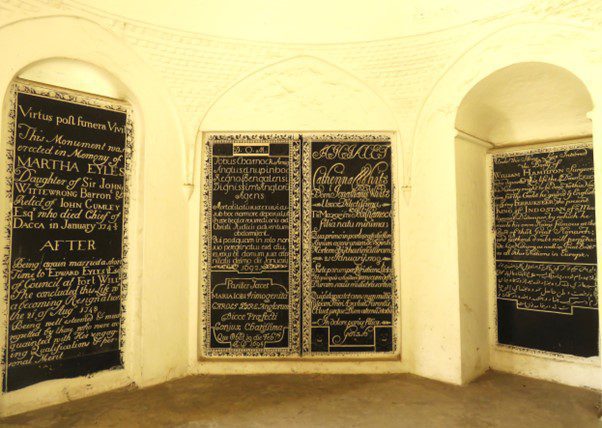

In the churchyard is a pretty, circular pavilion fusing Indian and British architecture and housing the memorial of Dr. William Hamilton. (Fig 4) It is inscribed in hard volcanic black basalt chosen for durability, with the lettering highlighted in white to impressive effect. Even more impressive is that part of it is written in Urdu. The English reads:

His memory ought to be dear to this Nation for the Credit he gained the English in curing FERRUSKEER, the present KING of INDOSTAN of a Malignant Distemper, by which he made his own name famous at the Court of that Great Monarch and without doubt will perpetuate his Memory as well in Great Brittn, as all other Nations in Europe.

That sounds ambivalent—does it mean Hamilton’s fame in Europe, or the King’s? The answer is in the Urdu underneath, which translates:

William Hamilton, physician, surgeon of the English company, who had gone along with the English Ambassador to the illustrious presence and had raised his name high in the four quarters of the world by reason of the cure of the King of Kings, the Asylum of the world, Mohammad Farakh Siyar the Victorious, with a thousand difficulties having obtained, from the Court of the Asylum of the World, leave of absence to his native land, by the decree of God, on the 4th December 1717, died in Calcutta and in this place was buried. [In the Islamic Hijri calendar, it is Muharram 1, 1130 As-Sabt.]

This seems to have been carved by an envoy from the Moghul Emperor sent from Delhi—then Shahjahanabad—to check on Hamilton, who was only meant to be on leave from the Moghul’s service. Hamilton had gone to the tenth Moghul Emperor Farrukhsiyar with a trade deputation and stayed on as his physician. He cured him of an abdominal abscess about to fistulate. The medical staffing arrangement also levered a trade deal. The Urdu records the Court’s obvious reluctance to let him go, even temporarily. There is nothing new in the fraught bureaucracy of doctors’ leave under assertive management. Almost incredibly, the Mughal Emperor’s envoy regarded Calcutta as British native land, while other native state rulers certainly did not.

Nevertheless, the monuments are wonderful artistic objects, with centuries-old lasting humanitarian stories in the maelstrom of international relations in the subcontinent. Hinduism, Christianity, and Islam were all important in the shaping of modern India. The doctors’ memorials not only embody Christianity, but reflect genuine care, tolerance, and integration across different communities and religions.

Further reading

- The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany. v. 2 1816.

- The Bengal Obituary. Holmes and Co, Calcutta, W Thacker and Co, London, 1851.

- “British Medicine in India.” Editorial. The British Medical Journal, Vol. 1, No. 2421, May 25, 1907, pp. 1245-53. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20294481 Accessed December 2023.

STEPHEN MARTIN works voluntarily in Thailand as an Honorary Professor of Psychiatry and running an arts education project.

Leave a Reply