The mammary glands are believed to have originated as glands in the skin of synapsids. These were the predecessors of mammals some 300 million years ago, and the function of their skin glands was to provide moisture for the eggs they were laying. When mammals came on to the scene, the function of the mammary glands evolved to provide nourishment for their newborn. Eventually humans learned to domesticate animals and to capture their milk for their own nutrition. In various cultures, milk was also used to treat diseases, promote healing, or enhance fertility. In the Greek story of Persephone, milk symbolizes nourishment and the sustenance of life, as does the reference to the “land of milk and honey” in the Old Testament.

Cleopatra is renowned for her legendary milk baths designed to enhance her beauty and skin health. In Indian Ayurvedic medicine, milk was often combined with turmeric or saffron to treat conditions ranging from inflammation to insomnia. In the Renaissance, milk has often been painted as a symbol of sustenance and of the fleeting nature of life, such as in Vermeer’s The Milkmaid and Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin’s The Morning Chocolate. In literature milk has been represented as a symbol of purity and innocence, also of comfort and domesticity like the warm milk given to a child before bed, or as lost innocence like the spilt milk metaphor. The term milk itself comes from the ancient meoluc, milc, melok, miluk, melk, or miluh.

Milk is a colloidal suspension that contains emulsified globules of fat, proteins, carbohydrates, lactose, minerals, and vitamins. It is also a source of protective agents such as antibodies, enzymes, and growth factors. Many factors affect the composition of milk. There are also significant differences between the composition and characteristics of the milk of various animals. Buffalo’s milk has more fat, protein, and lactose than cow’s milk. In parts of India, goats are a more popular source of milk. Asses’ milk was highly advocated for in Jane Austen’s novel Sanditon by the formidable Lady Denham.

Scientists have been particularly interested in colostrum, the first milk produced by mammals after giving birth. It is packed with antibodies and growth factors that support the newborn’s immune system and growth. In recent years, bovine colostrum has been studied for its potential in enhancing immune function and promoting gut health in humans.

An unwanted consequence of drinking cow’s milk is lactose intolerance. It affects some 70 percent of the global population, especially Asians, Africans, Hispanics, and Native Americans. It is caused by a deficiency of the enzyme lactase in the small intestine, leading to an inability to break down lactose into glucose and galactose. The lactose that cannot be absorbed remains in the intestine and draws water causing bloating, cramps, gas, and diarrhea. Symptoms of lactose intolerance range from mild to severe, depending on how much lactase a person can produce. Some people can tolerate small amounts of lactose, others cannot take any lactose without having symptoms and must limit themselves to lactose-free foods and milk.

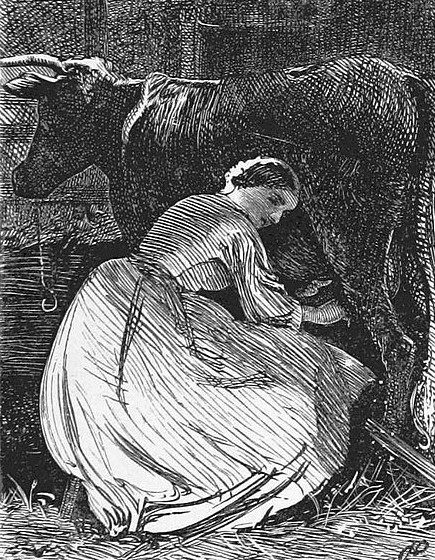

Milk allergies are also a concern, particularly in children. They range from hives and digestive symptoms to severe reactions, requiring the exclusion of milk and dairy products from diets. It has also been posited that a high milk intake may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, but this has not been proven. More importantly, raw milk has long been a source of bacterial infections such as diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, bovine tuberculosis, brucellosis, etc. These bacteria are now eliminated by the use of heat through various modifications of pasteurization, the process invented by Louis Pasteur in 1864. In our advanced industrial age, milk is now processed and delivered so as to make the traditional milkmaid with her pretty apron and the milkman who delivered the milk at the door in the early morning largely a sight of the past.

Further reading

- Editorial. Asses’ milk diet. Scientific American March 26, 1887;56(13):193.

- Mathilde Cohen. Regulating Milk: Women and Cows in France and the United States. The American Journal of Comparative Law 2017;65(3):469.

- Julie Laskaris. Nursing Mothers in Greek and Roman Medicine. Journal of Archaeology July 2008;112:459.

- Maurice Moscovitz. Milk Diet. Scientific American July 27, 1907;97:63.

- Bruce Pierce. Is raw milk a raw deal? Scientific American April 1932;146:212.

- George Thin. Curative Effects of Milk. BMJ Dec 4, 1897;1635.

- Josephine Joordens et al. On Breast Milk, Diet, and Large Human Brains. Current Anthropology February 2005;46(1):122.

- Editorial. Milk Diet and Moral Responsibility. BMJ 1904;2:1604.

Leave a Reply