Juliana Menegakis

St. Andrews, Scotland

Upon the death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286, the throne of Scotland passed to his four-year-old granddaughter Margaret. Only four years later, the young queen died, aged just seven. However, the exact details of her death are uncertain. When exactly did she die? And was her death a sudden tragedy, or a political assassination?

Alexander III of Scotland (1241–1286) had three children with his first wife, Margaret of England: Margaret (b. 1261), Alexander (b. 1264), and David (b. 1272). David died young, Princess Margaret married King Erik of Norway in 1281, and Prince Alexander married Margaret of Flanders in 1282. In 1283, Princess Margaret died giving birth to Margaret (known to historians as the Maid of Norway to distinguish her from her mother, known as the Maid of Scotland). Prince Alexander died in 1284, leaving no children. Finally, the widowed King Alexander’s second marriage to Yolande de Dreux yielded no children.1 As a result of this string of deaths, the only living descendant of Alexander III upon his death in 1286 was the young Maid of Norway.

As soon as Margaret became queen, the elites of both Scotland and England were eager to bring her from Norway to Britain. Edward I of England quickly set about arranging a betrothal between the Maid and his three-year-old son, which was finally settled in the 1290 Treaty of Birgham. Edward I sent a lavish ship to collect Margaret and bring her to England in May 1290. However, Margaret’s father did not allow her to leave on the English ship, and it returned to England on 16 June.2 Instead, Margaret left Bergen, Norway, in late August or early September. She and her retinue were bound for Orkney (part of Norway), travelling on one of her father’s ships. Accompanying her were several Norwegian representatives, who would conclude the marriage negotiations with the English and Scottish.3

By 8 September, Edward I had received “rumours of the arrival of the Maid at Orkney,” and her ship certainly arrived in Orkney by 23 September.1 However, the contemporary chronicles of Rishanger and Trivet agree that Margaret had taken ill on the voyage, and she lay ill in Orkney for several days before dying “attended by Bishop Narve [of Bergen], and in the presence of the best men who followed her from Norway.”4 English messengers had been sent from Northumberland to meet Margaret and her retinue in Orkney. However, they stopped in Skelbo on 1 October to meet Scottish messengers, who were probably travelling back from Orkney and carrying news of the Maid’s death.1 This exchange ensured that both the magnates of Scotland and the king of England would soon learn of her death. Indeed, the bishop of St Andrews wrote to Edward I on 7 October with rumors of Margaret’s death.5

The exact date of Margaret’s death is uncertain. Most modern historians put it between 26 and 29 September, which is based on the itinerary of the Scottish messengers.1 Even in optimal conditions, a small group could likely average only forty miles a day at this time.6 As such—adding a day for a boat ride from Orkney to the mainland—it probably took three days for the Scottish messengers to arrive in Skelbo on 1 October. If they were carrying news of Margaret’s death, then she could not have died on 29 September (only two days before the messengers arrived in Skelbo). On the other hand, if Margaret died on 26 September, why would the messengers wait to leave Orkney? This makes 27 or 28 September the most likely dates of Margaret’s death, though true certainty is probably impossible.

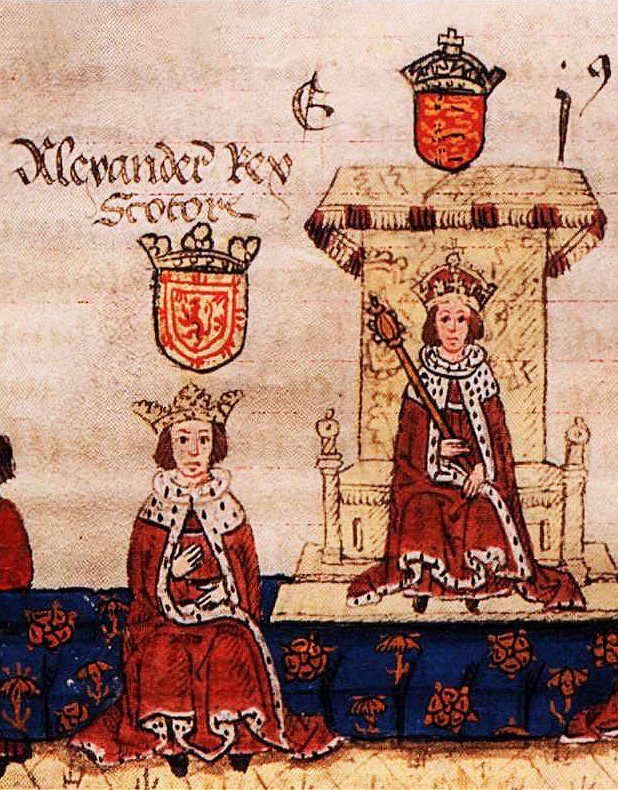

Margaret’s grandfather, Alexander III of Scotland (left), with his brother-in-law, Edward I of England. Crop of illustration from A. L. Rowse (1979), The Story Of Britain, London, via Hogyncymru on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0.

If the date of Margaret’s death is uncertain, then the cause of her death is even more so. The chronicles give no details, stating only that she “fell ill while upon the sea.”7 Historians usually attribute her death to either seasickness or food poisoning. Duncan rightly argues that seasickness is rarely fatal, but severe dehydration—caused by an inability to keep down fluids—can be.1 Furthermore, as a child of only seven, Margaret would have been especially susceptible to both dehydration and food poisoning. She also would have been susceptible to many forms of contagious illness, which travel quickly through ships even today. Margaret could have had a preexisting condition of some kind, which would explain why her father was unwilling to send Margaret across the sea. However, this reluctance easily could have been over relinquishing control of Margaret to the elites of Scotland or England. Regardless, contemporary sources barely note Margaret’s birth, let alone comment on any illnesses she may have had, so these must remain speculation. Either way, she “would be fit and well when she left Bergen.”1 As an alternative to these natural causes, Margaret may have died as part of a purposeful strike against either Norway or Scotland.

Despite her young age, Margaret was already a prime target for political violence. She was the last legitimate, direct descendant of her great-great-grandfather, William I of Scotland. As a result, the line of Scottish succession was unclear beyond Margaret, devolving to the competing claims of descendants of King William’s brother David. Upon Margaret’s death, conflict between these descendants sparked a civil war that was not fully resolved until 1328.8 As such, Margaret’s death would have been a major success for those wishing to cause chaos in Scotland or wishing to advance their claim to the throne. Furthermore, she may also have been a target for enemies of Norway. At the time of her death, Margaret’s father, King Eric, was a widower with no other children. However, Eric was only 22 and would go on to remarry, and also had a younger brother.9 This meant that Norway’s line of succession was much more secure than Scotland’s, making Margaret’s death less significant for Norway than Scotland.

How might Margaret’s assassination have been accomplished? As Duncan points out, “the ship was her father’s, whose suppliers may have poisoned her with decaying food.”1 However, poisoned supplies would suggest that others would have been impacted. Again, a child would have been more susceptible to poisoned food, but there is no record of any other members of Margaret’s party falling ill. Despite the short mentions of her death in the chronicles, one imagines that suspicions of poisoning—or another type of assassination—would have been noted. Similarly, an outright attack would surely have been noted. Despite the clear motivations for an assassination, it seems that Margaret probably died of natural causes.

Upon Margaret’s death in Orkney, her body was transported back to Bergen for burial. There, she was met by her father, who “had the coffin opened, and narrowly examined the body, and himself acknowledged that it was his daughter’s body,”4 before having her buried “beside her mother on the north side of the choir of Bergen cathedral.”5 Her father’s confirmation of Margaret’s death is important, as a woman claiming to be Margaret appeared in Norway in 1300.

According to the Iceland Annals, “a German woman” claiming to be Margaret attested that “she had been sold by Ingibiorg Erlingsdatter,” the highest-ranking lady of those traveling with Margaret to Orkney. This could suggest that Ingibiorg raised suspicions at the time, but she and her husband remained in high esteem at the Norwegian court, so there were probably no rumors of their involvement in Margaret’s death. Furthermore, a 1320 letter from Bishop Audfinn of Bergen states that the false Margaret “was greyhaired and white in the head” and was in fact seven years older than her supposed father, King Eric. The imposter did gain some supporters, but she and her German husband were imprisoned and personally questioned by King Haakon. Soon after, in the autumn of 1301, the false Margaret was found guilty of treason and burnt to death at Nordnes, while her husband was beheaded.4 These executions effectively ended the legacy of Margaret in Norway, as the Norwegian throne passed along Haakon’s line rather than Eric’s.

Margaret’s legacy in Scotland was even more dramatic, and much more long-lasting. Upon her death, the two main rivals for the Scottish succession were John Balliol and Robert Bruce, both direct descendants of King William’s brother David. Unable to decide between them, the Scottish magnates invited Edward I of England to arbitrate. He chose John Balliol to succeed but invaded Scotland in 1296, forcing John’s abdication. After a long period of Scottish resistance, Robert Bruce was crowned king in 1306, but intense conflict with England continued. This First War of Scottish Independence did not end until, in 1328, Edward III was forced to recognize Scotland’s independence and Robert Bruce’s position as king.8 This could perhaps mark the end of Margaret’s legacy in Scotland, but the Second War of Scottish Independence saw a similar conflict between the Bruces and the Balliols. At the very least, this conflict over the throne would not have taken place had Margaret lived to pass the throne to her children. Indeed, had she married Prince Edward of England, they may have ushered in a period of peace, rather than the era of conflict of the Scottish Wars of Independence.

Margaret’s date and cause of death may forever be unclear. However, her importance to Scottish history is undeniable, her untimely demise plunging Scotland into wars from which it would emerge forever changed.

Bibliography

- Duncan, A. (2002). The Kingship of the Scots, 842-1292: Succession and Independence. Edinburgh University Press.

- Dunbar, AH. (1899). Scottish Kings; A Revised Chronology of Scottish History, 1005-1625. David Douglas.

- Helle, K. (1990). Norwegian Foreign Policy and the Maid of Norway. The Scottish Historical Review, 69(2), pp. 142-156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25530460.

- Anderson, AO. (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286. Oliver and Boyd.

- Bain, J. (ed.) (1884). Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, Vol. II: A.D. 1272-1307. https://www.electricscotland.com/history/records/bain/calendarofdocuments02.pdf.

- Harvey, B. (2001). “Introduction.” In Harvey, B. (ed.), The Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, 1066-c.1280. Oxford University Press, pp. 1-30.

- Rishanger, W. (2012). “Willelmi Rishanger, Monachi S. Albani, Chronica.” In Riley, H. T. (ed.), Willelmi Rishanger Chronica et Annales: Regnantibus Henrico Tertio et Edwardo Primo, AD 1259-1307. Cambridge University Press, pp. 1-230.

- Penman, M. (2002). The Scottish Civil War: The Bruces & the Balliols & the War for Control of Scotland, 1286-1356. Tempus Publishing.

- Bjørgo, N., Norseng, P. G. and Andersen, P. S. (2023). “Eirik Magnusson.” In Store Norske Lexikon. https://snl.no/Eirik_Magnusson.

JULIANA MENEGAKIS is a second-year student studying history at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

Leave a Reply