Michael Yafi

Chaden Yafi

Houston, Texas, United States

|

| Maurice Ravel in his hometown, 1914. Via Wikimedia. |

The world is commemorating the 95th anniversary of Maurice Ravel’s Boléro. The composer continues to be one of the most enigmatic classical music personalities. Born in 1875 in Ciboure, France, he displayed from an early age a keen interest in the piano. Guided by his father, who would offer him ten sous to practice the piano daily for half an hour, Ravel’s passion for music flourished. He enrolled at the Paris Conservatory, where he studied piano first and then composition under the guidance of Gabriel Fauré.

Ravel never engaged in any romantic relationships, and his sexuality remains enigmatic. His profound love for his mother endured, and no woman could fill the void she left. He had a penchant for collecting children’s toys, preserving a sense of childlike innocence that found its expression in some of his works, such as Ma mère l’oye and L’enfant et les sortilèges.

At the beginning of World War I, Ravel tried to enlist as an aviator, but was not accepted because of his slight build and short stature. Ultimately, he joined as an ambulance truck driver. After the war, he began to notice changes in his physical and mental well-being. He channeled his emotions into his musical compositions, exemplified by his piano piece Le Tombeau de Couperin, which consists of six pieces dedicated to each of his friends who had died in the war. He also crafted a piano concerto for the left hand intended for his pianist friend Paul Wittgenstein, who was the sibling of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein and had lost his right arm in the war. In 1920, Ravel voiced his struggle with a profound “tristesse affreuse” (terrible sadness).1

In 1926, Ravel was said to experience “l’anémie du cerveau,” or cerebral anemia, characterized by confusion, insomnia, and intellectual inertia. As a composer renowned for his elegant craftsmanship, he grappled with errors in writing, uneven lines, and erasures. The initial indications of a neurological disorder surfaced in 1927, particularly in his becoming disoriented while performing his own compositions.2 His physician, Valery Radot, advised a year’s rest, a recommendation Ravel chose not to adhere to.

In 1928, during a performance of his Sonatine for piano in Madrid, Spain, Ravel had a distressing memory lapse, causing him to skip from the first movement to the coda (last part) of the piece.3 Concurrently, he experienced challenges in articulating his thoughts verbally, struggling to find the appropriate words.

In defiance of his doctors’ recommendations, Ravel embarked on a tour in the United States. During this successful tour, he was influenced by American music, particularly by jazz and blues. He also visited the Ford Automobile factory, which captivated him with the sheer power of its machinery and intricacies of the mechanical processes.

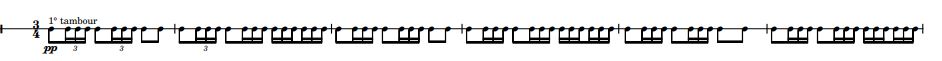

Immediately after his visit, Ravel composed his renowned piece, Boléro. It is now estimated that Boléro is performed, either in its original composition or as an arrangement, about every six minutes worldwide, making it the most frequently performed musical composition globally. The composition rests on two fundamental principles: ostinato and crescendo. Ostinato refers to a repetitive motif in the bassline, in this case the two measures’ rhythmical pattern (below) that is played by the snare drums and repeated 169 times.

|

On the other hand, crescendo entails a gradual increase in loudness, which Ravel achieved through dynamic shifts and by introducing additional instruments into the musical fabric. This work demonstrates Ravel’s remarkable orchestration skills, influenced by great Russian composers such as Mussorgsky and Borodin. Moreover, the Boléro incorporates Arabic-Spanish rhythms, drawing inspiration from his Basque heritage.

The renowned musicologist Émile Vuillermoz once remarked, “Any person on the street can enjoy whistling the initial measures of the Boléro, but only a handful of professional musicians possess the capability to flawlessly reproduce, from memory, the entirety of the thematic phrase.”4

Ravel’s neurological condition raised the question of whether he stood at the brink of dementia when composing Boléro, given his persistent repetition of the same musical phrase without progression or contrast. Ravel noted his intention to test the orchestra’s capability to construct an unending crescendo; he never envisioned Bolero evolving into such a renowned musical composition.

The medical history of Ravel has fascinated neurologists. Compulsive, fastidious, and perfectionist, he had suffered from mild head trauma from a car accident in Paris in 1932 and started to develop progressive apraxia and aphasia in middle life.5 His neurologist, T. Alajouanine, presented his case at a neurology congress.6 Over time, his symptoms became worse. He was very annoyed by his declining mental capacity and by not recognizing his own compositions, feeling that he no longer had music in his head. And yet, he said, he once had so much of it: “Et puis, j’avais encore tant de musique dans la tête.”

Ravel was operated on by the well-known Parisian neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent to rule out a brain tumor but found no abnormality. Ravel improved briefly, but by the end of December 1937, he lapsed into a coma and died.

In exploring the interplay between his artistry and mental health, we come to appreciate the nuanced textures of his work, evermore mindful of the complex harmonies that echo the depths of the human soul. As the French poet Alfred de Musset said two centuries ago: “The suffering of artists is never in vain.”

Further reading

Maurice Ravel’s neurologic disease, George Dunea

References

- Seddon, Andrew. “Music Inexpressible: The Tragedy of Maurice Ravel.” Medical Problems of Performing Artists 10, no. 2 (1995): 63.

- Henson, RA. “Maurice Ravel’s Illness: A Tragedy of Lost Creativity.” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 296, no. 6636 (1988): 1586.

- Henson, “Maurice Ravel’s Illness.”

- Augé, Lucie. “Le Boléro de Ravel, une oeuvre révolutionnaire.” Étudiante Journalisme. https://etudiantejournalisme.wordpress.com/2014/12/12/le-bolero-de-ravel-une-oeuvre-revolutionnaire.

- Warren J. “Maurice Ravel’s amusia.” JR Soc Med. 96, no. 8 (2003):424. doi:10.1177/014107680309600831.

- Vitturi, BK and Sanvito, WL. “Maurice Ravel’s dementia: the silence of a genius.” Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 77, no. 2 (2019):136-8. doi:10.1590/0004-282X20180134.

MICHAEL YAFI, M.D., is a professor of pediatrics and the Division and Fellowship Director of Pediatric Endocrinology at UTHealth (The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston).

DR. CHADEN YAFI holds degrees from Boston University’s College of Fine Arts (PhD, Musical Arts), Longy School of Music (MA, Piano Performance, Graduate Performance Diploma), and Damascus University (BA, Pharmacy). She has worked at the University of Houston, Tufts University, and Boston University, and has also lectured at Dartmouth College and the Jung Center in Houston. She has published several research articles in music, as well as three books.

Leave a Reply