JMS Pearce

Hull, England

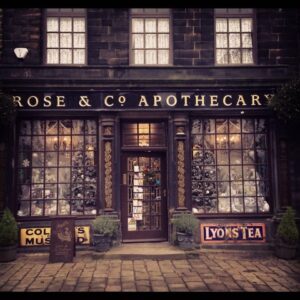

Some of us oldies may remember the word “apothecary” above a pharmacist’s shop window or in old photographs (Fig 1).

But how did the apothecaries come to be? And how did they relate to Medicine? There are early records of pharmacy in Mesopotamia around 2600 BC, the main elements being herbal remedies. The word apothecary came from the Greek Φαρμακοποιός, and Latin apothecarius: a storekeeper. In the thirteenth century, an apothecary was little more than a grocer. He kept a store or shop that stocked spices, herbs, preserves, and “oyntments, sirops, waters.” London apothecaries were originally members of a livery company, the Grocers; both started in the Guild of Pepperers (responsible for the purity of spices) founded in 1180 who were incorporated as the Worshipful Company of Grocers in 1428. Chaucer’s Nun’s Priest’s Tale (translated in modern English) illustrates that drug regulations were non-existent:

Though in this town is no apothecary,

I shall myself two herbes teache you,

That shall be for your health, and for your prow;

And in our yard the herbes shall I find…

And it was a skilled apothecary from whom Shakespeare’s Romeo (written c. 1591–6) sought a potent drug to end his own life when he thought Juliet was dead. As he felt its rapid effects he gratefully acknowledged:

“O, true Appothecary: Thy drugs are quicke.” (Romeo & Juliet v. iii. 119)

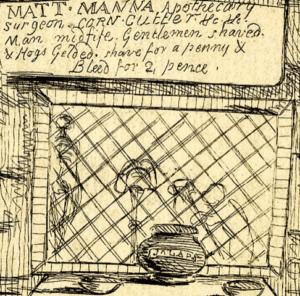

In medieval times, infections were rife in village streets and homes besieged by poverty, foul water, and the stench of untreated excrement. Different healers attended the sick: apothecary, barber-surgeon, surgeon, and physician. Apothecaries worked as general practitioners, providing medicines to qualified medical practitioners, and to the man in the street. Along with foods and herbs, they sold spices, purgatives, laxatives, emetics comfits, antidotes, aphrodisiacs, antiseptics, and tonics for medicinal purposes (Fig 2).

Their shelves were laden with jars, bottles, and Winchesters bearing labels in Latin and containing an astonishing variety of medicaments. For instance, topical oil of earthworms was recommended for painful joints. Snail water was used for colic, yellow jaundice, falling sickness, and convulsion.

Opium and quinine apart, most medicines had little efficacy but tasted foul or bitter to convince patients of their therapeutic potency. Recipes dispensed as powders, pastes, or liquids included herbs, minerals, and strangely selected bits of animals. The witches in Macbeth recount:

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder’s fork and blind-worm’s sting,

Lizard’s leg and howlet’s wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

The Worshipful Company of Barbers was recognized in 1308 and the London Guild or Fellowship of Surgeons in 1435. When not cutting hair or trimming beards, barbers thrived as tradesmen: bloodletting, pulling teeth, hernia repairs, cutting for stone (bladder), cupping, and applying leeches. The red-and-white-striped barber’s pole found outside their shops showed the blood and bandages used in bloodletting.

The crucible of knowledge and skills of apothecaries, like doctors and barber-surgeons themselves, was shallow, with limited regulation. Practice was mainly determined by the masters to whom they were apprenticed. In 1518, Dr. Samuel Johnson observed:

When Linacre’s scheme was carried into effect, the practice of medicine was scarcely elevated above that of the mechanical arts; nor was the majority of its practitioners among the laity better instructed than the mechanics by whom those arts were exercised.1

Ambroise Paré (1510–1590) was outstanding amongst the barber-surgeons. He greatly advanced the surgery of war injuries and devised techniques to aid wound healing, bloodletting, blood vessel ligation, and Caesarean section. He was admitted to the College of Surgeons in 1554 and is sometimes described as the “Father of Modern Surgery.”

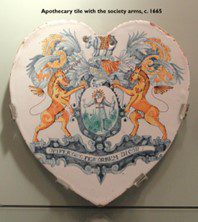

An Act of Parliament joined the Fellowship of Surgeons to the Company of Barbers in 1540. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries, to regulate their practices, acquired jurisdiction over apothecaries’ trade.2 It was incorporated by royal charter in 1617 and thereby separated from the grocers. Its motto (Fig 3) was taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where Apollo says: Inventum medicina meum est, opiferque per orbem dicor, et herbarum subiecta potentia nobis [Medicine is my discovery, I am called help-bringer throughout the world and the subject of herbs is in our power].

Herbal remedies were commonplace, so that in 1673 Sir Hans Sloane donated the Chelsea Physic Garden (now containing 4,500 plant species) to the apothecaries. But the longstanding conflict between apothecaries and medically qualified doctors was unallayed, motivated mainly by money and status. Alexander Pope scorned the apothecaries’ role when in 1713 he remarked: “My Friend an Apothecary! a base Mechanic!” In fiction, Anthony Trollope’s Dr. Thorne was a medically qualified rural apothecary, who prescribed herbal medicines, but was disdained by the city physicians for preparing medicines in his shop and “vulgar ointments for agricultural ailments.”3

Thomas Linacre founded the College of Physicians in 1518. With undisguised derision it claimed the right to control “those lowly dispensers of drugs and boluses.”2 Physicians’ knowledge was also primitive and almost certainly killed as many patients as they cured.1 Standards improved when in 1618 the College published the first pharmacopoeia; its use by apothecaries was supposedly compulsory.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, apothecaries were more numerous than physicians accredited by the College of Physicians. Apothecaries, purveyors of folk–medicines, and barber-surgeons provided both diagnoses and treatments without formal training.4 Some, like Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1742–1786), made major contributions to experimental and organic chemistry. Foremost in their ranks stood Nicholas Culpeper, an astrological apothecary, botanist, and infamous rebel against both medical and political establishments. He is still known for his Complete Herbal, an enduring text.5

The College of Physicians’ hegemony with exclusive rights to practice medicine was shattered in 1704 when they sued a London apothecary, William Rose, for practicing illegally as a physician while treating a butcher.

At first, apothecaries were restricted on pain of imprisonment to a seven-mile radius within the city of London until the Apothecaries Act of 1815. This act enabled those holding the license by examination in medicine and surgery of the Society of Apothecaries (LMSSA) to practice medicine throughout the country without a university degree. The Conjoint diploma of the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons (LRCP, MRCS) performed a similar function. The LMSSA ceased to be recognized by the General Medical Council as a medical qualification in 2008. The society, housed at Black Friars Lane, continues valued educational and charitable services.

The subsequent 1841 Medical Reform Bill prevented chemists and druggists from dispensing medicines unless medically qualified. This removed the need for a separate pharmacy profession and quickly provoked their disquiet and the formation of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in April 1841. A Royal Charter was awarded in 1843 to advance chemistry and pharmacy and promote a uniform system of education for them. An official register of pharmaceutical chemists followed in 1852.

There were similar issues in Europe.6 For example, in France surgeons wore long robes, barber-surgeons short robes. Apothecaries were regulated under the Collège de Pharmacie established in 1777. They manufactured, dispensed, and sold medicines, but did not practice general medicine as they did in England. In 1840, the Collège was affiliated to the universities and conferred degrees.

In America, medical practice was less stringently regulated. Physicians dispensed their own drugs, and often had a shop for this purpose. Apothecaries, a profession defined only by the possession of a shop for the sale of drugs, also practiced medicine qua physician and sold toiletries like a shopkeeper. There was little control and no requirement for formal education. America’s first hospital, Pennsylvania Hospital, in 1751 was also the first to have an associated apothecaries’ shop for patients, which “curbed the need for apothecaries to act as both doctor and pharmacist.”7

Assistant physicians and independent prescribers

The current American Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination (PANCE) does not permit the supply or prescription of medicines, but different legislation may apply in other countries. In the UK, until recently only medically qualified practitioners were granted the rights to prescribe any licensed medicine, including controlled drugs. Like many former exclusively medical privileges, this right has been delegated. The Human Medicines Regulations 2012 permits “Nurse Independent Prescribers and Pharmacist Independent Prescribers to prescribe, administer, and give directions for the administration of Schedule 2, 3, 4, and 5 Controlled Drugs.”8 This extends to diamorphine, dipipanone, or cocaine for treating organic disease or injury within their own level of professional competence and expertise, but not for treating addiction.

Post scriptum nostalgia

I well remember as a boy seeing bottles and Winchesters of medicines then current on the shelves in my father’s surgery, and my failing to remember their names and uses!

Aqua Menth Pip

Mist Pot Brom and Nux Vomica

Mist Mag Trisil and Belladonna

Mist Morph and ipecac

Tinct ipecac

Mist cretae aromat cum opio

Mist Ferri cum strych

Mist Ferri et arsen

Tinct Digitalis

Note

* Still situated in Main Street in Haworth, Yorkshire, home of the Bronte sisters. Their brother Branwell Bronte (1817–1848) satisfied his fatal laudanum addiction by purchasing it from this shop’s owner, Joseph Hardaker. More recently it became The Old Apothecary, and now The Cabinet of Curiosities.

References

- History of the Royal College of Physicians. From https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/about-us/who-we-are/history-royal-college-physicians.

- Copeman WSC. The Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London-1617-1967. British Medical Journal 1967;4:540-1.

- Dunea G. Doctor Thorne, a country apothecary. Hektoen International Journal, Winter 2023. https://hekint.org/2023/01/23/doctor-thorne-a-country-apothecary/.

- Reinarz J. The transformation of medical education in eighteenth‐century England: international developments and the West Midlands. History of Education 2008; 37:4, 549-566, DOI: 10.1080/00467600802109846.

- Culpeper N. The English Physician (The complete herbal) 1653. Full text at https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/49513.

- Puett SB, Puett D. The Florentine Renaissance apothecary. Hektoen International Journal, Fall 2014. https://hekint.org/2017/01/30/the-florentine-renaissance-apothecary/.

- Wust M. The Evolution of the Apothecary for the Apothe-curious. Penn Medicine News, October 13, 2017. https://www.pennmedicine.org/news/news-blog/2017/october/the-evolution-of-the-apothecary-for-the-apothecurious.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Non-medical prescribing. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/medicines-guidance/non-medical-prescribing.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 16, Issue 1 – Winter 2024

Leave a Reply