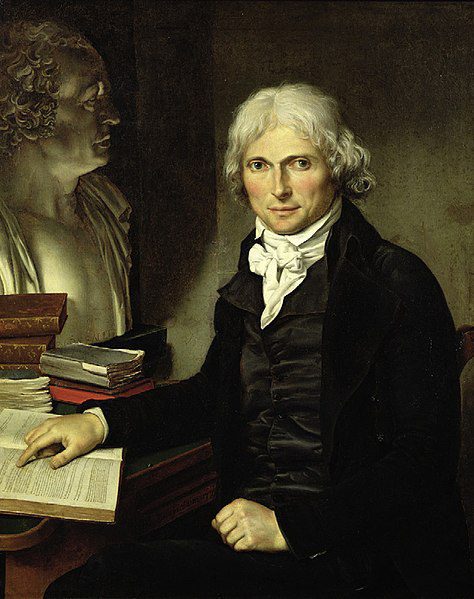

In the universal Pantheon of the medical greats, Xavier Bichat is remembered as “the father of modern histology.” Yet he never used a microscope. He studied the human organs with his naked eye and evaluated them for their physical features (such as elasticity, transparency, and hardness). He postulated that each organ was not a homogenous structure, as was then believed, but rather composed of several different materials or tissues that he called membranes. This change in emphasis ultimately served as a bridge from the earlier organ pathology of Morgagni to the later cellular pathology of Virchow.

Bichat was born in 1771 in a small town in the Jura in the east of France. At an early age, his father, a provincial physician, sent him to study the classics at a local school and subsequently philosophy in Lyons (1788). When the French Revolution broke out, he returned home, and his father taught him anatomy. Between 1790 and 1792 we find him back in Lyons studying mathematics and philosophy but also anatomy and surgery. In 1793, he served as army surgeon in the Revolutionary Army. A year later, in 1794, he moved to Paris to study under the famous surgeon Joseph Desault.

Desault recognized the young man’s talent. He invited him to stay with him as his secretary and surgical assistant; and in 1795 promoted him to editor of his surgical journal (Journal de Chirurgie). By the age of twenty-four Bichat had published the three volumes of his chief, and then used his military connections to obtain permission to dissect and experiment upon the fresh bodies of those who had been guillotined. In 1799 he abandoned surgery to devote himself to anatomy and physiology. In 1800 he was appointed to the staff of the Hotel Dieu, the preeminent hospital in Paris.

During the winter of 1801, he opened more than six hundred corpses. He experimented with drugs and studied their action on tissues; he investigated the effects of blood transfusion, of oxygen deprivation, of cross circulation, and of introducing air bubbles into the veins. He promoted the theory of vitalism and considered the passions linked to specific organs, fear to the stomach, anger to the liver, goodness to the heart, and joy to the viscera! He studied cancers and divided them into different categories.

Bichat postulated that each organ was composed of at least some of the twenty tissues (membranes) such as nervous, vascular, mucous, muscular, epithelial, or connective tissue. Each tissue could be affected independently by a disease, which therefore need not necessarily be confined to a single organ but could be widespread. He also stressed the distinction between external organs such as voluntary muscle or sense organs and the internal organs such as the lungs, heart, and liver. Understanding the tissue changes in disease carried the promise of eventually leading to a cure.

As a descriptive anatomist, he is remembered eponymously by Bichat’s fossa (pterygopalatine fossa), Bichat’s protuberance (buccal fat pad), Bichat’s foramen (cistern of the vena magna of Galen), Bichat’s ligament (lower fasciculus of the posterior sacroiliac ligament), Bichat’s fissure (transverse fissure of the brain), and Bichat’s tunic (tunica intima vasorum). He was extremely productive and completed four substantial texts of pathology within five years. He died prematurely in 1802 from tuberculosis, typhoid, or a fall at the age of thirty-one. He was considered to have been brilliant medical pioneer, the role model Tertius Lydgate wished to emulate in George Eliot’s Middlemarch.

When in 1845 his body was disinterred to be moved to a cemetery for illustrious persons, the head was surprisingly found to be missing. It was then produced without any further explanation by a physician who had done the autopsy forty-three years earlier and was reunited with the rest of the body. Several statues have been raised in his honor, the first ordered by Napoleon, then still First Consul, in 1802, in the grounds of the Hotel-Dieu Hospital and followed in later years by several others. A street on the right bank of the Seine in Paris has been named after him. He is indeed deserving to be remembered as one of the greats of medicine.

Further reading

- Androutsos G, Diamantis A, and Vladimiros L. Cancer’s conceptions of Marie François Xavier Bichat (1771-1802), founder of histology. Journal of BUON 2007;12:295-302.

- Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, et al. Marie-François Xavier Bichat (1771–1802) and his contributions to the foundations of pathological anatomy and modern medicine. Annals of Anatomy 2008;190(5):359.

- Marie-François-Xavier Bichat. Wonders of the World. https://www.wonders-of-the-world.net/Eiffel-Tower/Pantheon/Marie-Francois-Xavier-Bichat.php.

Leave a Reply