Simon Wein

Petach Tikvah, Israel

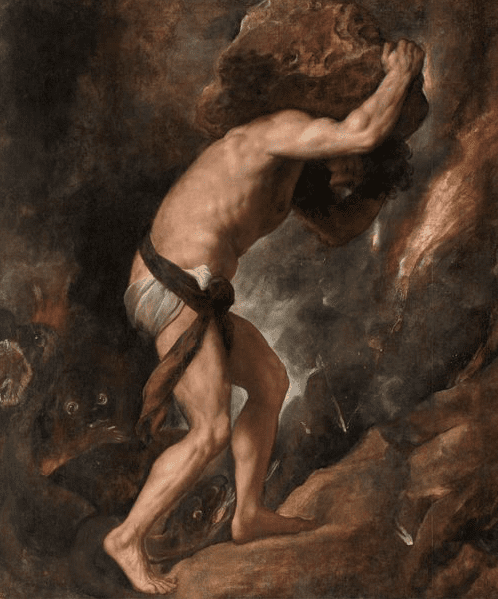

Albert Camus (1913-1960) was a French writer and philosopher. He did not want to be pinned down as an existentialist or an absurdist, or indeed a nihilist. Nevertheless, he is well known for coining the expression ‘the absurd hero’. Camus used the Greek myth of Sisyphus to illustrate this idea. Sisyphus’s punishment was to push a boulder up the hill and let it roll down again and to repeat this for eternity. This challenges the ideals of having a meaningful and useful life and serves as a metaphor for the insignificance of our lives in a meaningless universe. Camus was able to add ‘hero’ to the absurd exercise because Sisyphus learned to accept his fate and to live with it:

‘I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.’1

Translated to daily life, this moral tale challenges us to accept the drudgery and daily grind of going to the office or the coal-pit or the cleaning job, and yet to imagine ourselves happy. Camus suggests that if we can achieve this equanimity, we are heroic.

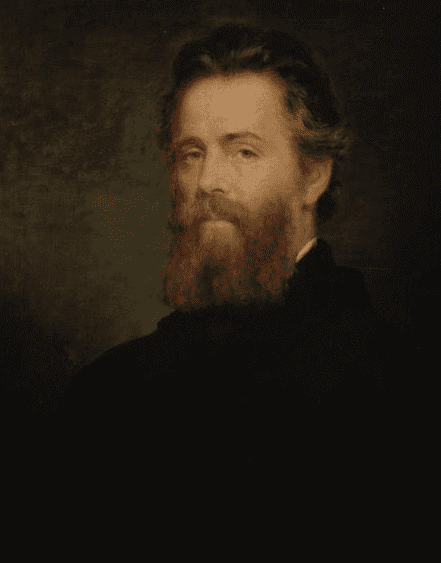

Herman Melville (1819-1891) is considered a great American author, and his novel Moby-Dick is one of the great American novels. However during his lifetime, he was not recognized as such. Melville had to wait 100 years after his own death for scholars to gradually realize the significance of his literary achievements. Less well known maybe, is that Melville wrote in a number of genres including novels, travelogues, poetry and short stories. One of his short stories, Bartleby, the Scrivener is a remarkable work which touches on the theme of absurdity and one way of living an absurd life, most apropos palliation and psycho-oncology.2

Camus admired Melville as a ‘philosophical novelist’.3 The character Bartleby, that Melville so vividly drew, would have attracted Camus’ attention as a nascent creature of absurdity.

The philosophy of the absurd is based on the unpleasant feeling we experience, when, in spite of a search for meaning and significance in our lives we realize that the universe is uncaring, unresponsive and without ultimate meaning. Our experiences of suffering and anguish exacerbate the absurdity of our fruitless search. Our own emptiness reflects a world bereft of meaning.

With this in mind, we can look at Melville’s story as a tale of absurdity. The story is absurd: a man sitting at a desk looking out of his window onto a wall in Wall Street, New York; a man who refuses to work, who stonewalls, without offering explanation, but expects to continue to be employed; a man who ends up using his work-place as living quarters; a man who seems able to dictate to his employer the conditions of employment; an employer, being unable to remove Bartleby from his premises, instead, removes his work-premises from Bartleby; the new renters contact the lawyer and ask him to take Bartleby back, a discarded possession. A litany of multiple absurd scenes. Yet, despite all this, Bartleby appears on the surface as a man at peace, polite and honest – no anger nor violence nor histrionics – doing nothing.

Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener is a sad, frustrating, enigmatic, angering, and perplexing story. All this and its absurd atmosphere leads us to think about the meaning of Bartleby’s life and why he chose to behave as he did.

The word that binds and shapes the story, like a corset, is ‘prefer’. Bartleby, when asked to do something, simply and without vexation replies: ‘I would prefer not to’.2 With that quiet passive statement, he does not, ‘do’. ‘Prefer’ is a brilliant device in the absurd world, since it implies reflection and a delicate non-commitment. Absurdity is about the meaninglessness of choice-making.

Melville could have had Bartleby say, ‘I will not do it’ or ‘I do not want to do it’ or have Bartleby make excuses for not complying, such as fatigue, pain or ill-health. Instead, ‘prefer’ delivered civilly, is less confrontational in a psychological sense, and philosophically implies considered choice.

Some commentators have suggested severe depression as Bartleby’s ailment, but the evidence does not support this. Bartleby searched for the job interview, he worked diligently for a few days in order to establish himself in the office, then purposively did nothing. A person with severe depression would find it difficult to generate the energy to search for work, let alone articulate ‘prefer’. More likely they would be distressed, sad, monosyllabic, dishevelled, paralytically unmotivated, distressed, crying. Melville attributed none of this Bartleby. Throughout the story, Bartleby was able to arrange purchase of biscuits and functioned, albeit within the limits of his volition. His mood was at most subdued.

Alternatively, and I think this is what Melville is portraying, Bartleby had fully considered life. Bartleby found no purpose or meaning, as a scrivener in copying someone else’s writings and then proof-reading them. So he stopped. Life was purposeless and he had reached a dead-end as Melville alluded to. Bartleby’s previous job was in the ‘Dead-end letter’ department of the Post Office. Similarly, facing the wall outside the office window without a view, without a future, was another dead-end. The meaningless of life. Quite Kafkaesque.

Had Bartleby been one of Camus’ ‘absurd heroes’, he would have accepted life-fate-existence and lived earnestly, enthusiastically for each day, for each moment, like he imagined Sisyphus. Camus describes suicide as an alternative to the terrible angst of absurdity. Philosophical suicide, Camus suggests, is where people create a false world, in which meaning is created by adopting a Creator or a Dictator, as the raison d’être.

The other suicide is physical – either a self-inflicted gun wound or chronic suicide by consciously stopping to live, to work, to eat. There being no meaning in this world, and I, being of the constitution that I cannot create meaning, I should logically stop doing anything to prolong my painful sense of the absurd. I will withdraw from life. By chronic suicide – which seems to be how Melville described Bartleby’s purposeful inanition – one also avoids the problem of the absurd. One escapes angst, as surely as does philosophical suicide.

Melville’s use of ‘prefer’ gives pause to ponder, that Bartleby prefers and chooses to die by withdrawing from life and not eating, rather than to go on living in an absurd, meaningless world. Melville again uses the metaphor of a wall, as ‘here and no further’, when describing Bartleby’s death: ‘Strangely huddled at the base of the wall, his knees drawn up and lying on his side, his head touching the cold stone.’2

This view of Bartleby sadly does not emplace him as a hero against the absurd; rather as a person who could not muster the resources to cope with reality without meaning. However his lawyer-employer was shaken to the core: ‘Something prompted me to touch him. I felt his hand, when a tingling shiver ran up my arm and down my spine to my feet.’2

Unconsciously or otherwise, the lawyer was electrified about the ramifications of an absurd death.

References

- Camus A. The myth of Sisyphus, 1942 https://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil360/16.%20Myth%20of%20Sisyphus.pdf (free e-book)

- Melville H. Bartleby, The Scrivener, 1853. https://www.bartleby.com/129/ (free e-book)

- Seltzer LF. Camus’s Absurd and the World of Melville’s Confidence-Man, PMLA, Mar., 1967, Vol. 82, No. 1, pp. 14-27 https://www.jstor.org/stable/461042 (free e-book)

- Ricci, Roberto. Used with artist’s permission. https://www.artstation.com/robertoricci76

SIMON WEIN graduated from Melbourne University Medical School and then specialized in Medical Oncology, Psycho-oncology and Palliative Medicine. His interests include how we cope with death and dying. Currently he is studying English Literature at Bar-Ilan University.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply