Edward Tabor

Bethesda, MD, United States

Harvard University President James B. Conant had the idea of sending a fully staffed hospital to England to help the British in their war with Germany in 1939, more than two years before the US entered the war. It became a collaboration between Harvard University and the American Red Cross. They sent prefabricated hospital buildings, a team of Harvard doctors and laboratory technicians, a team of American Red Cross nurses, and laboratory and clinical equipment. The first physicians were sent in August, 1940.

The hospital was intended to provide medical care to infectious disease patients in southwest England and to investigate epidemics throughout the country. It was also intended to study how epidemics are transmitted between civilian and military populations in wartime. Heavy bombing was expected, and large civilian crowds in air raid shelters for many hours might lead to epidemics, which could then spread to the military.

The entire project was dangerous. When the director of the hospital, Dr. John E. Gordon (previously Professor of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology at Harvard Medical School) arrived in London, a falling bomb destroyed his apartment, and he suffered scalp injuries and bruises. As the days rolled on, Dr. Gordon noted the unearthly “day-in and day-out, night-in and night-out pounding, under which the British capital lives, the waiting for the banshee wail of the alarm … and the shattering of bombs, which one waits to fall.”1

The Atlantic crossing and torpedoes

Everything for the new hospital had to be transported across the Atlantic in convoys guarded by warships. In regions of the Atlantic where submarine attacks were most likely, hospital staff were told to sleep in their clothes and to keep a life jacket and a small bag (with passport and first aid kit) nearby. They were asked to stay awake until 2 a.m. and take afternoon naps, so that they would be asleep for fewer of the dark hours when a submarine attack was more likely.2

In June 1941, a British convoy carrying twenty-nine nurses for the hospital was attacked on its seventh day at sea. The SS Vigrid, which had been lagging due to engine trouble, was torpedoed and sunk. The ten nurses on board were lowered into three lifeboats; one drifted for twelve days until rescued, one drifted for nineteen days, and the third lifeboat, with four nurses, was never found. Eight days later, the SS Maasdam in another convoy was torpedoed and sunk; from that ship, the nurses’ chaperone and one nurse were lost when their lifeboat sank.

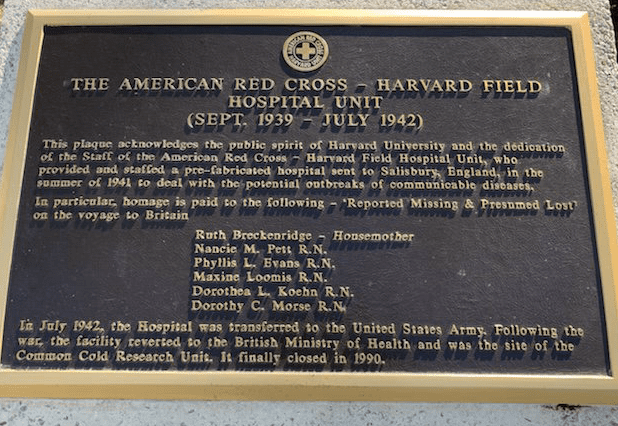

Outside the American Red Cross headquarters at 17th and E Streets, NW, Washington, DC, you can see a plaque that says: “This plaque acknowledges the public spirit of Harvard University and the dedication of the staff of the American Red Cross – Harvard Field Hospital Unit.” It lists the names of the American Red Cross nurses and their chaperone who died when their ships were torpedoed.

The hospital

The hospital officially opened on September 22, 1941 on Salisbury Plain, one and a half miles from the city of Salisbury. Nearby there were large military training facilities including live firing ranges. The hospital consisted of twenty-two prefabricated buildings made of wood on steel frames, which had been shipped to England in 250,000 pieces in thirty ships. It had a capacity of 125 hospital beds.

The landscape in many parts of southwest England consists of chalk covered by a layer of turf. During construction, the exposed chalk on the ground made the location very visible to planes flying over and “one had the uncomfortable feeling of living on a rather obvious target,” in the words of one of the physicians.3 Later, the chalk was covered again with topsoil and fortunately, the hospital itself was never bombed.

There were three residential buildings with individual sleeping quarters for each staff member, as well as an administration building, a kitchen and dining room building, a recreation building, and a laboratory building. The recreation building had an assembly room, three parlors, a game room with ping pong, a kitchenette, and a library. There was also a “men’s club room” for men only, about which one of the women wrote, “They need a retreat, poor dears, since the place will be overrun with women.”4

The staff

The American Red Cross-Harvard Field Hospital eventually had ten physicians, sixty-two nurses, six technicians, and eight administrative staff. Many of the physicians had been on the staff of Harvard Medical School or its hospitals, including two residents (one of whom, Paul Beeson, would later edit the two major internal medicine textbooks used by a generation of US physicians) and one clinical fellow.

Although the work was intense, there was also time off. The summer days were long because from 1940 to 1945, England was on “double daylight savings time” in summer, i.e., two hours ahead of the peacetime clocks in winter. Letters5 written to family back in the US describe bicycle rides after work to nearby villages and Roman ruins along the country lanes with high hedges on either side, surrounded by fields with wildflowers. On weekends they sometimes bicycled to Stonehenge, about ten miles away. Dances, skits, and other gatherings were organized in the recreation room, and the staff sometimes went by bus to attend dances at other hospitals, or on weekends to London by train, about eighty miles away.

Medical and scientific contributions

In 1940, the infectious disease environment was very different from today. There were almost no antibiotics for civilian use and there were fewer vaccines than today. The epidemiological staff of the hospital, known as the Harvard Public Health Unit, investigated infectious outbreaks throughout Great Britain and Northern Ireland, including outbreaks of scabies, trichinosis, paratyphoid fever, “epidemic respiratory disease,” “epidemic myalgia,” mumps, meningitis, typhoid fever, tuberculosis, and “food poisoning.” They investigated an outbreak of smallpox in Glasgow. In early 1942, in parallel with similar investigations in the US, they investigated an outbreak of 1,591 cases of hepatitis among US troops in Northern Ireland caused by a contaminated yellow fever vaccine. At least seven scientific papers about some of these investigations were published between 1941–1942 by the hospital staff.6

In 1941, the British Ministry of Health wrote to tell Harvard University management about one of these investigations:

Let me tell you what happened in Bristol a few weeks ago. That city, which has suffered severely from air raids and whose health department has been seriously overworked, was visited by a widespread epidemic of paratyphoid fever. The resources of the city proved inadequate to the occasion, and Dr. Gordon was asked to help. He sent six of his nurses to the local isolation hospital to lend a hand there. Another six public health nurses, together with a doctor, took charge of the field work and two laboratory technicians undertook all the necessary laboratory work. As a result, the situation was brought rapidly under control, and Dr. Gordon earned the gratitude of the whole city.7

The hospital and its American doctors, nurses, and technicians also provided moral support for the British war effort. Dr. Gordon wrote in October, 1940: “The fact that Harvard University had made a formal and definite offer of medical assistance within a few weeks after the collapse of France – when British prospects appeared blackest – had created a profound impression. … [and led to] excellent opportunities for service, both to a people who are bearing an unbelievable strain with marvelous fortitude, and in the advancement of medical knowledge.”8

The US entered World War II in December 1941, and US forces were soon arriving in England to prepare for further battles. On July 15, 1942 the American Red Cross-Harvard Field Hospital was transferred to the US Army Medical Corps, and its laboratory became the central US military laboratory for the European theater of operations. At the time of the transfer, some of the hospital staff, including Dr. Gordon, joined the US Army; thirty of the nurses transferred to the US Army Nurse Corps, and twelve others continued to work in the UK as civilian nurses. After the war ended, the hospital buildings were given to the British government.

References

- Gordon J.E. “The Harvard Unit in London.” Harvard Alumni Bulletin, Oct. 5, 1940, p. 19–21.

- Jaqua, Mary Alice. Letters of Mary Alice Jaqua. The Mary Alice Jaqua Papers, in the Ella Strong Denison Library, Special Collections at Claremont Colleges, Claremont, CA.

- Houser GF. “Harvard and the Red Cross in England,” Harvard Alumni Bulletin, October 4, 1941, pages 16–18.

- Jaqua, op cit.

- Ibid.

- Various documents, including article reprints. Clippings – Harvard-Red Cross Unit – England – 1940-1942. Countway Library, Harvard University, Boston, MA.

-

Vivette, P.B. “The United Kingdom.” In Lada J. and Hoff E.C.: Preventive Medicine in World War II, Volume VIII. Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army, Washington, DC, 1976, pages 375–376.

- Gordon, op. cit.

EDWARD TABOR, M.D., was an associate director at the National Cancer Institute, NIH; a director of two divisions at FDA; and a vice president at Fresenius Kabi. He is an author of more than 300 publications on viral hepatitis, liver cancer, pharmaceutical regulatory affairs, and medical history.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the Center for the History of Medicine, Countway Library, Harvard University, Boston, MA; the Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Claremont, CA; and the Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library, The George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 14, Issue 4 – Fall 2022

Leave a Reply