Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

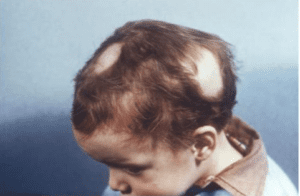

| Hair loss in child with tinea capitis infection. CDC, 1970. Public domain. |

Overconfidence is an undesirable quality. It does not enhance a physician’s approach to learning, nor to changing when change is needed. How a doctor diagnoses or treats a condition today may cause future generations of physicians to wonder, “What were they thinking? Did they not think about potential long-term effects?” Such future physicians will probably find different and better diagnostic and treatment techniques, which may be questioned in their turn by even later generations.

Tinea capitis, or ringworm infection of the scalp, was treated by low-dose irradiation of the scalp until the second half of the twentieth century. This treatment has produced long-term consequences. The infection is caused by a fungus, either Trichphyton or Microsporum, which lives inside the hair shaft. The lesions consist of round areas (hence “ringworm”) on the scalp where the hair shafts are broken off close to the scalp, giving bald-appearing patches. Fungal infection of hair (or nails), in contrast to infection of hairless skin, cannot be successfully treated by topical agents. Traditionally, instead of waiting until puberty for the infection to resolve,1 unfortunately with scarring and permanent bald spots,2 plucking out each infected hair was curative.

In 1907, not a decade after Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays, tinea capitis was treated by irraditation.3 The purpose was to kill the growing hairs (it did not kill the fungus) and make them fall out spontaneously after several rounds of treatment, or helped along by later applying and removing hot wax to the scalp.4

By 1949 it was believed that tinea capitis was “most efficiently treated by [X-ray] epilation of the scalp.”5 It was state-of-the-art treatment. Confidence was manifested by statements such as, “X-ray treatment has been all too infrequently used because of the fears engendered by the damaging effects of radiation…prior to the introduction of a reliable method of dosage measurement.”6 In a discussion which followed the article cited above, a physician stated, “[I]t is hard to be sure that no bad effects will follow later, even many years later.” He did think, however, that X-ray epilation was safe “if done right and only once.”7

In Israel between 1946 and 1960, 20,000 immigrant children – mostly from North Africa and the Middle East – were treated with X-ray therapy, as well as 50,000 children (1950-1959) in the former Yugoslavia, and also children in Syria, Morocco, Portugal, the UK, and the US. About 200,000 children worldwide received scalp irradiation.8

A study followed 1,900 children who were treated by irradiation epilation thirteen years earlier.9 There were three cases of leukemia, one of aplastic anemia, and six other cancers in the irradiated group, and one cancer in a control group of children who had had tinea capitis. Of note, there were no meningiomas in either group.

|

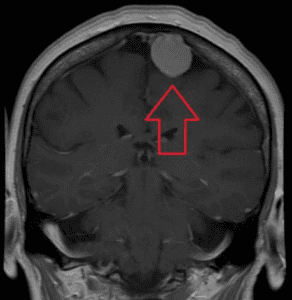

| MRI, coronal image, of a meningioma with contrast. James Heilman, March 28, 2016, via Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

Meningiomas were, however, seen on longer-term follow-up studies in the late 1960s and early 1970s.10

A meningioma is a tumor formed by overgrowth of the meninges, the membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. They comprise 30% of “brain tumors,” though strictly speaking they are not composed of brain tissue. More than 90% of meningiomas are benign and most are asymptomatic. Symptoms occur when the growing tumor mass compresses brain structures or blood vessels. Symptoms may consist of seizures, headache, vision or behavior changes, leg weakness, and incontinence.11

A significantly increased incidence of meningioma was found in Israel in irradiated patients as compared to a matched, non-irradiated group.12 The average time between irradiation and the development of a meningioma (the “latency period”) has been found to be about thirty-six years,13 with a range of 29-48 years.14,15 Radiation-induced meningiomas differ from other meningiomas in that they have more rapid growth, more aggressive biologic behavior, and a greater tendency to be malignant and multiple. They are discovered at an earlier age and have a higher recurrence rate after removal.16,17 Today, head irradiation is recognized as a cause of meningioma.18,19

Griseofulvin, an oral antifungal drug, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 1959. It became the standard treatment for tinea capitis. There are currently a number of effective oral antifungals available.

The Israeli government has paid financial compensation to the victims of their irradiation campaign.20

Note

Title quote attributed to Aesop.

References

- ME Mottram and Harold Hill. “Radiation therapy for ringworm of the scalp,” Calif Med, 70(3), 1949.

- Rebecca Kreston. “The ringworm irradiators,” Discover Magazine, 2015.discovermagazine.com

- Raphael Pfeffer and Yaacov Lawrence. “Radiation epilation of tinea capitis: A historical review,” Int J Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 2012.

- Kreston, “Ringworm.”

- Mottram, “Radiation.”

- Mottram, “Radiation.”

- Mottram, “Radiation.”

- Kreston, “Ringworm.”

- Roy Albert, Abdel Omran, et al. “Follow-up study of patients treated by X-radiation for tinea capitis,” AJPH, 56(12), 1966.

- Mottram, “Radiation.”

- Meningioma. Wikipedia.

- Siegal Sadetzki, Baruch Modan, et al. “An iatrogenic epidemic of benign meningioma,” Am J Epidemiol, 151(3), 2000.

- Siegal Sadetzki, Pazit flint-Richter, et al. “Radiation-induced meningioma: A descriptive study of 253 cases,” J Neurosurg, 97(5), 2002.

- Salvatore Giaquinto, Guido Massi, et al. “On six cases of radiation meningiomas from the same community,” Ital J Neurosurgical Sci, 5, 1984.

- Leo Pollak, Natalie Wallach, et al. “Meningiomas after radiotherapy for tinea capitis — still no history,” Tumori J, 84(1), 1998.

- Sadetzki, “Radiation-induced.”

- Dov Soffer, Stefania Pittaluga, et al. “Intracranial meningiomas following low-dose irradiation to the head,” J Neurosurg, 59(6), 1983.

- Pfeffer, “Radiation epilation.”

- Sadetzki, “Radiation-induced.”

- Kreston, “Ringworm.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Spring 2022 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply