Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“Abandon all hope, ye who enter here”

— Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy

When the American Civil War (1861–1865) began neither the Union nor the Confederacy gave much thought to housing prisoners-of-war (POWs). Eventually, the two opposing sides had a total of about 120 POW camps.1 The two armies had captured a total of 674,000 POWs, of which about 400,000 were confined to prison camps. Of this number, 56,000 (14%) died.2 Thus, prison camp mortality was higher than battlefield mortality.

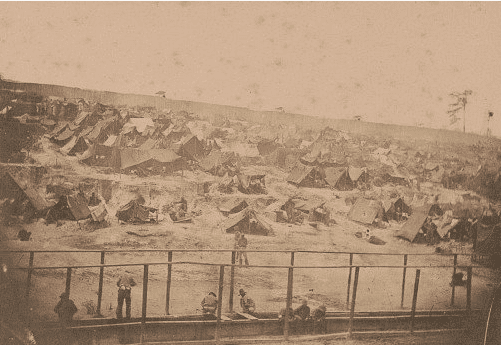

The worst camps were at Andersonville, Georgia, for Union prisoners and at Elmira, New York, for Confederates. The Andersonville prison camp, officially known as Camp Sumter, had 45,000 Union POWs pass through its gates and 13,000 (28%) died there. The prison had been built to hold about 10,000 prisoners but at one time held 33,000,3 making it the fifth largest “city” in the Confederacy.4 At that point, each prisoner had 36 ft2 (about 3.3 m2) to live in.5 “This density is enormous, and cannot be tolerated by animal life in any climate, in any latitude of the world,” it was said at the end of the war.6

Summers in Georgia were hot and often sunny. Temperatures rose to 110o F (43oC) or more. Annual rainfall was 55 in (140 cm).7 In the winter months, there were nights with freezing temperatures and some men froze to death.8 The men were given no shelter and no barracks or tents were provided. Some men created makeshift shelters of scrap wood or improvised tents from blankets or pieces of cloth.

Food was in short supply for civilians in the South, for the Confederate Army, and certainly for the prisoners. They received four to six ounces (114–170 g) of cornmeal or cornbread twice a day. The cornmeal was coarsely ground and about 20% of it was ground corn cob. This irritated the men’s digestive systems and caused abdominal pain and diarrhea. They received about 170 g of beef or bacon a few times a week. They had no plates or utensils and nothing to cook their food in.9 Local farmers preferred to sell their produce to civilians at a higher price than the Confederate Army could pay. Corn could profitably be made into whiskey. Some large landowners continued to grow cotton and not foodstuffs. The army also ordered food (often meat) from outside contractors who were usually late with deliveries and provided low quality meat.10

Captured Union soldiers who were American Indians were sent to Andersonville, as were Black Union soldiers. The Black soldiers could be re-enslaved once in the Confederacy. White officers of Black units could be executed as leaders of a “slave insurrection.”11

What made Andersonville unlivable and unbearable (and Elmira as well) was the lack of sanitation. A stream ran through the camp at Andersonville and was used for drinking (upstream), bathing and as a latrine (downstream). But it was already contaminated from an upstream Confederate Army post. The stream flooded at times and produced a swamp of three or four acres in the camp. The men defecated, urinated, bathed in, and drank from this stagnant water, which became increasingly contaminated with visible fecal matter and debris. The camp smelled of rotting food, excrement, and gas gangrene. Inspectors would vomit from the smell upon entering the camp. The water was a life-threatening source of bacteria. Diarrhea and typhoid fever resulted from drinking it. It was also too filthy to use for washing.12 Everyone had lice; flies and rats were everywhere; and wounds had maggots.13 Rats infested the camp.

The prisoners were preyed upon by a gang of robbers and murderers, the “Andersonville Raiders,” made up of some of their fellow Union soldiers. These men would take anything of value from fellow prisoners, usually from those who had newly arrived, even if they had to kill to do it.14

The diet produced malnutrition and scurvy, which was a major cause of death. Diarrhea, dysentery, and anasarca accounted for many more.15 These four conditions accounted for 80% of the 13,000 Andersonville deaths. “The homesickness and disappointment, mental depression and distress attending the daily longings for an apparently hopeless release was as potent…in the destruction of these prisoners as the physical causes of actual disease.”16

There were suicides among the prisoners. Men would cross the line (the “deadline”) near the prison wall, beyond which they were shot on sight.17 Hookworm, a parasitic disease that produces weight loss and anemia and is transmitted by larvae in the soil, was also common among the barefoot prisoners.18 It is possible that the prisoners’ diet, lacking in niacin (vitamin B3) caused them to develop pellagra,19 another cause of diarrhea, and eventually death. The dietary deficiency causing pellagra was not confirmed until the early twentieth century.

The physicians of the Confederate Army stationed at Andersonville were generally from rural communities and were untrained in military medicine.20 The Civil War was the last major war before the germ theory of disease was accepted by physicians.21 The hospital at Andersonville could hold 1,400 patients. In June 1864 there were 3,000 sick men in need of hospitalization. There were periods during which 76% of hospitalized patients died.22 Bandages and dressings were inadequately washed and reused. The Union had declared medical and surgical instruments, medications, and textbooks of medicine as contraband of war. Supplies were very limited for the Confederate Army and for Union prisoners at Andersonville. Doctors resorted to local herbs and plant material used in folk remedies. For example, a decoction (a concentrated solution made by boiling a substance) of red oak bark was used as a wound disinfectant. Physicians tried, without success, to grow poppies in Georgia and North Carolina in the hopes of producing opium.23 The commandant of Andersonville was Hartmann Heinrich “Henry” Wirz, a native of Zürich, Switzerland. It has been repeatedly written, incorrectly, that he had trained as a physician,24 but he was actually a self-declared homeopathic “physician.”25,26

Confederate soldiers confined to the Union POW camp at Elmira, New York suffered, too. They called the place “Hellmira.” The camp, originally Camp Rathbun, opened in the summer of 1864. It was built for 5,000 prisoners but eventually held 12,000 POWs.

Of these, 3000 (25%) died, a mortality rate twice that of other Union POW camps. Prisoners were sent there before housing barracks had been completely built. Tents housed 900 men until January 1865.27 The winter of 1864-1865 was particularly severe in upstate New York. Temperatures dropped to -18oF (-28oC), and sometimes two feet (61 cm) of snow was on the ground. Men froze to death.28

The prisoners’ breakfast was six ounces of bread and a small piece of meat. Supper was six ounces of bread again and a watery soup. The men caught and ate rats and the occasional dog.29 Soon after the camp opened, President Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, changed the diet of Southern prisoners in a sort of spiteful revenge for the treatment of Northern soldiers in Andersonville. The prisoners in Elmira were given a diet of bread and water beginning in August 1864.30 By mid-September, 1,870 cases of scurvy were diagnosed among the Elmira prisoners. The bread-and-water diet was continued until December 1864.31

The men had no blankets. In another spiteful move, the only clothing prisoners could wear from those sent by family and friends were grey in color. Clothing of any other color was burned.32

Captured Confederate soldiers who were American Indians were sent only to Elmira.

Elmira was built and run like Andersonville, without attention to water supply and sanitation. A stream fed a pond in Elmira. Sometimes the stream overflowed its banks and sometimes the stream and the pond froze. The pond was used as a latrine and a dump. It was quickly contaminated with fecal bacteria and as in Andersonville, accounted for much death and illness. The major causes of death at Elmira were diarrhea, pneumonia, and smallpox.33 In both Andersonville and Elmira, doctors vaccinated prisoners against smallpox. In general, medical care was poor in both camps, although in Elmira there was no lack of supplies.

Newspaper readers in the North read much about Andersonville but understandably, little about Elmira. After the war ended, Henry Wirz, the commandant of Andersonville, was tried by a jury of senior Union officers and found guilty of conspiring to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States. He was hanged November 10, 1865.34

No one was charged or tried for the catastrophe that was Elmira.

References

- Ashley Luskey. “Under the enemy flag: prisoner of war experiences. An interview with Angela Zombek and Michael Gray,” The Gettysburg Compiler, 2018.cupola.gettysburg.edu

- Alexander Mikabeidze, ed. Behind the barbed wire: an encyclopedia of concentration and prisoner of war camps, Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2019.

- Andersonville-Wikipedia.

- Jerry Staub. “Sherman’s inability to liberate the South’s most notorious prison,”ehistory.osu.edu, ND.

- Gabriel Hunter-Chang.” Sensing the past: nighttime at Andersonville prison-American Civil War Museum,” acwm.org, 2021.

- Augustus Hamlin. Martyria; Or Andersonville Prison, Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1866.

- Hamlin. “Martyria”

- Norton Chipman. The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison, Trial of Henry Wirz, the Andersonville Jailer, Jefferson Davis’ Defense of Andersonville Prison Fully Refuted, San Francisco: Bancroft Company Publishers, 1891.

- Kathy Weiser-Alexander. “Andersonville prison of the civil war.” Legends of America, 2021. legendsofamerica.com

- NA. “Myth: You starved our prisoners and we took care of yours,” Andersonville National Historic Site (US National Park Service), 2015. nps.gov

- Dora Costa. “Scarring and mortality selection among civil war POWs: A long-term mortality, morbidity, and socioeconomic followup,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2010. nber.org

- Andersonville-Wikipedia.

- Gary Miller and Peter Adler. “Drenched in dirt and drowned in abomination: Insects in the civil war,” In Proceedings of the DoD symposium on evolution of military entomology, 2008. apps.dtic.mil

- Andersonville-Wikipedia.

- NA. “Causes of death at Camp Sumter-Andersonville National Historic Site,” US National Park Service, 2022. nps.gov

- James Breeden. “Andersonville – a southern surgeon’s story,” Bull Hist Med, 47(4), 1973.

- Hamlin. “Martyria.”

- Andersonville-Wikipedia.

- Costa.”Scarring.”

- Mary Marshall. “Medicine in the Confederacy,” Presented at the 44th annual meeting of the Medical Laboratory Association, 1942.

- Miller. “Drenched.”

- Rachel Noll. “The ghost that still remains: The tragic story of Andersonville prison,” inside.nku.edu, ND.

- Marshall. “Medicine.”

- NA. “Andersonville prison – location,” Civil war history, 2019. history.com

- Albert Winkler. “Henry Wirz and the tragedy of Andersonville: A question of responsibility,” Swiss American Historical Rev, 50(3), 2014. scholarsarchive.byu.edu

- Henry Wirz-English Wikipedia. wp-en.Wikideck.com

- NA. “Elmira prisoner of war camp,” ND. mycivilwar.com

- NA. “Elmira prison-Wikipedia,” ND. en.wikipedia.org

- James Robertson, jr. “The scourge of Elmira,” In Civil War Prisons, William Hesseltine, ed, Kent Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1962.

- NA. “Medical care at Elmira prison camp,” WSKGWSKG, 2016. wskg.org

- NA. “Medical care.”

- Laurence Hauptman. Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War, New York: Free Press Paperbacks, 1995.

- NA. Mycivilwar.com.”Elmira prisoner.”

- wp-en.Wikideck.com.”Henry Wirz.”

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.